Earthling: Cold War II goes lunar

Plus: Warfighting robots, LA’s climate cope, mass extinction or mass panic?, paid subscriber perk, and more!

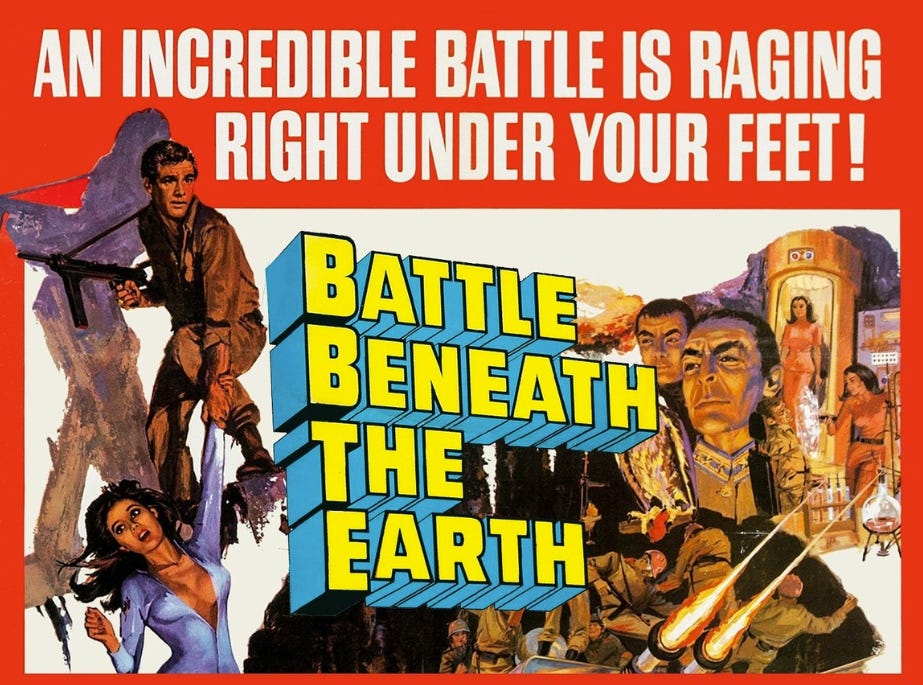

In the 1967 movie Battle Beneath the Earth, US officials are disconcerted to find that Chinese Communists are underfoot—literally underfoot, having dug tunnels under the Pacific Ocean, continued their burrowing under American soil, and set about placing nuclear bombs in key locations. One of these officials, reflecting on the strategic blunder that has placed America in peril, points to outer space and says, “While we’ve been wasting billions out there, they’ve been working down there, where it counts.”

Fast forward half a century, from Cold War I to Cold War II. Have US officials learned the lesson of that movie? No! Just last week, NASA director Bill Nelson contended that America should pour lots of money into countering the Chinese threat in outer space.

To put a finer point on it: Nelson worries that China will establish a base on the moon, declare the entire orb theirs, and threaten to use force should American astronauts set foot there. He told a Politico reporter that “we better watch out that they don’t get to a place on the moon under the guise of scientific research. And it is not beyond the realm of possibility that they say, ‘Keep out, we’re here, this is our territory.’” After all, “look at what they did with the Spratly Islands.”

A periodical more pedantically inclined than the Earthling might point to a number of relevant differences between the Spratly Islands and the moon. (For example: The moon is farther away from China than the Spratly Islands are.) Instead, we will make several quick points, starting with two that are sympathetic to Nelson.

1) Among the jobs of a NASA administrator—or the head of any big government agency—is to promote political support for robust funding. A tried and true way of doing that is to depict the funding as vital to fending off some threat from a perceived enemy. Given that NASA’s current showcase project is Artemis—which aims to revive manned missions to the moon and ultimately establish a base there—it’s only natural for Nelson to put that threat in a lunar context.

2) You have to give Nelson points for execution. Politico gave its piece on his warning a billing that looks like it was written by publicists at Mission Control:

Obviously, the 80-year-old Nelson learned a thing or two about media management during his decades in the House and Senate.

3) If Nelson were the only one in Washington trying to monetize fear of China, the dangers of that enterprise wouldn’t be worth a lot of worry. But he’s not. Lots of government officials and lobbyists are playing roughly the same game, and their number is growing. And often their pitches will be, if less glaringly dubious than warnings of a looming lunar showdown with China, dubious nonetheless. If enough of these funding pitches succeed, that could amount to a large diversion of resources to projects that are wasteful if not counterproductive and even dangerous.

4) One of the great fears of Cold War II hawks is that if the US is insufficiently vigilant, China’s authoritarian and autocratic model of government will become the global norm. That’s not impossible, but the most likely way for it to happen is for America to fail as a nation and therefore as a model for other nations—fail to show the world that a liberal democracy can prosper and flourish, fostering material, moral, and spiritual fulfillment and serving the values of justice and compassion. Making America that kind of shining city on a hill is a challenge; it will require, especially in a time of rapid and unsettling technological change, focus and imagination and wise investment in public goods. Getting wrapped up in mindless Cold War competition will make that harder—and will increase the chances that some future US government official, reflecting on America’s failure to inspire admiration and emulation around the world, will say of China, “They’ve been working down here, where it counts.”

Writing in The Spectator, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger sketches a Russia-Ukraine peace plan. The contours of the plan aren’t crystal clear (whether because Kissinger is a master of diplomatic ambiguity or because he’s 99 years old or both), but they would seem to leave room for a deal whereby Ukraine gets to join NATO and Russia keeps much of the territory it occupies (assuming the results of “internationally supervised referendums” in “particularly divisive territories” went Russia’s way).

This idea of Ukraine getting NATO membership in exchange for accepting the permanent loss of territory is actually one that has emerged in the Friday Nonzero podcast a couple of times (most recently in the year-end edition). Like most peace plans, it’s a long shot, but it does address the most common objection to any near-term deal: that the Ukrainian leadership would never accept the loss of territory that Russia would insist on. Actual NATO membership, after all, is a pretty big compensation for that loss.

This idea also gets discussed near the end of a Nonzero podcast conversation with Slate columnist Fred Kaplan that taped this week. That conversation—which is mostly a debate about the Ukraine war and US foreign policy—will be posted next week but is available now to paid NZN subscribers. They can watch or listen to it here and will also find it in their podcast feeds.

In The Guardian, Katharine Gammon details the steps Los Angeles is taking to make climate change more bearable for Angelenos. For example: creating shade by planting thousands of trees and cooling buildings by coating roofs with sunlight-reflecting materials. Streets, too, will be made to reflect more light and so absorb less heat.

These measures will address Los Angeles’s severe case of “urban heat island effect,” in which buildings, roads, and other artificial surfaces trap heat. But some of the measures will also have global effects; trees, in addition to providing shade, absorb carbon dioxide and so slow climate change. And a cooler roof can mean less power consumed by air conditioning—which will often mean reduced consumption of fossil fuels.

The Ukraine war has hastened the coming of drones that identify and strike targets without human input, according to a report by Frank Bajak and Hanna Arhirova of Associated Press.

Western nations already supply Ukraine with semi-autonomous drones; a human chooses the target, and AI does the rest. Experts say Ukraine could modify these drones to make them truly independent. It’s less clear how close Russia is to these capabilities, but Iran, a supplier of drones to Russia, says some drones in its arsenal feature advanced AI. Bajak and Arhirova write: