Afghanistan: 3 Unlearned Lessons

Why does America keep making the same mistakes over and over?

This is a free edition of the Nonzero Newsletter. If you like it and you’re not already a subscriber to the paid version of the newsletter (aka The Apocalypse Aversion Project), I hope you’ll consider becoming one.

As America’s longest war officially ends, expect to see a lot of “lessons learned from Afghanistan” pieces. Here is my candidate for most important lesson learned: that we never learn our lessons.

Some of the biggest mistakes America made in Afghanistan over the past 20 years are mistakes America has made—and famously made—in previous military engagements. Some of them have also been made by other countries in their own massively destructive wars—wars that either began for no good reason or were prolonged for no good reason or both. When it comes to war, our species seems a little slow on the uptake.

I have some ideas about what parts of human nature keep us making the same old mistakes, and I hope to explore that subject in future issues of this newsletter. Maybe I’ll even come up with a grand unified theory—or, at least, a few half-baked conjectures—about what aspects of our psychology do the most to make war a (so far) perennial feature of human experience. But for now I’ll hold off on the bigthink and just cite three big lessons from Afghanistan that were also lessons from Vietnam. I think these lessons add up to a fourth lesson: We should try really, really hard to avoid military interventions in the future.

Unlearned Lesson #1: The presence of a foreign army can strengthen the enemy by expanding its popular support.

In Vietnam, the United States underestimated the enemy’s grassroots support by misunderstanding the enemy’s nature. Many American officials saw the Viet Cong as fundamentally an incarnation of Communist ideology—and to some extent as a creation of outside Communist powers. They failed to see that it was in large part an incarnation of nationalism, of longstanding resistance against Western powers—first France and now the United States. So they didn’t appreciate that the presence of American troops was a kind of fuel for the enemy.

This misunderstanding was a central theme of Frances FitzGerald’s 1972 book Fire in the Lake. The book won a Pulitzer Prize and was a New York Times bestseller—which you’d think would be enough to keep FitzGerald’s point circulating for a long time.

Not long enough, apparently. In Afghanistan we again failed to see how a foreign military presence could energize nationalism and expand the enemy’s base. In a way our failure to get this picture is understandable; the Taliban seemed first and foremost a religious organization, and to the extent that it had a secular identity, that identity seemed rooted more in Pashtun ethnicity than in Afghan nationality. But such is the galvanizing power of a foreign army—especially one whose drones occasionally kill civilians—that unlikely carriers of a nationalist torch can wind up carrying it.

I didn’t totally get this until I listened to a recent edition of Aaron Mate’s Pushback podcast. Daniel Sjursen, a retired Army officer who served in both Iraq and Afghanistan and has taught at West Point, told Mate that “we kind of made the Taliban… What we ended up doing by our very presence was forming them into the national resistance organization they always wanted to be.” The Taliban became “the only game in town” for nationalists; the Taliban could say, “I'm a real Afghan. I'm a nationalist Afghan. Those people in Kabul, they're working with the Americans.”

Sjursen added, “And we never got that. We thought that, well, more militarization will fix the problem of militarization being the problem.”

Unlearned Lesson #2: Reports about a military intervention that travel through military channels are subject to systematic corruption.

The other big Vietnam book that came out in 1972 was The Best and the Brightest, by David Halberstam. One point Halberstam made is that, though the military brass can be counted on to emphasize the pitfalls and perils of a proposed intervention, once the intervention has happened, Pentagon assessments turn from negative to positive; no commanding general wants to report that he’s failing, so he gathers evidence of progress and downplays evidence of failure—and his preference for good news tends to become known, and indulged, at lower levels of the chain of command.

Here, again, Sjursen’s experience is pertinent. In Afghanistan, he helped manage a “cash-for-work” program, which involved giving Afghans money to do jobs that needed doing (and, sometimes, jobs that didn’t). Sjursen concluded, on the basis of circumstantial evidence, that some of the money from this program was going to the Taliban—a kind of tax the Taliban exacted from the workers in exchange for letting the program proceed without violent disruption.

Since showering the enemy with money wasn’t exactly a key mission objective, Sjursen figured he should tell the colonel he reported to about this possible downside of the cash-for-work program. The colonel, he says, replied, “Listen, the brigade commander likes the cash-for-work stats. You've got the best cash-for-work program going in the battalion, maybe in the brigade. This is a big good news story for you.” Needless to say, Sjursen’s suspicions never got higher in the chain of command than that colonel.

The speed with which the Afghan army collapsed this summer, and the ease with which the Taliban took city after city, caught pretty much every American official by surprise. That surprise shouldn’t surprise us, given that these officials had been getting feedback about the war that was, predictably, biased in a positive direction.

Unlearned Lesson #3: Countries are really complicated, full of cross-cutting allegiances and internal tensions that you need to understand if you’re going to invade and occupy them.

In Vietnam, most of the population was Buddhist, but much of the political and military elite was Catholic, a legacy of French colonial rule. America’s alliance with the elite—with Catholic presidents Diem and Thieu, with various Catholic generals—thus acquired a second significance, one that became especially problematic as a Catholic-led South Vietnamese government cracked down on growing Buddhist protests. America was not only a Western country seen as a threat to Vietnam’s national identity but a Christian country seen as a threat to Vietnam’s religious identity.

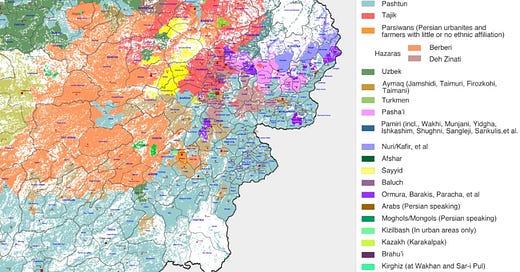

In Afghanistan ethnic divisions were marked less by religion than by language. Still, they posed the same generic problem that the US had encountered in Vietnam: Americans would sometimes find themselves linked to one ethnic group in a way that alienated another ethnic group.

As Sjursen explains, soldiers in the Afghan army tended to come from the North, and many didn’t speak Pashto, the dominant language of the south. So, when they tried to police Pashtun areas, things often didn’t go smoothly.

Sjursen says his colonel was slow to grasp this problem. And a one-star general “was surprised when I explained to him that I'm having trouble because my allied Afghan soldiers… from the north are seen as almost as much outsiders as me, and sometimes they were pretty brutal, so that turned a lot of the people towards the Taliban.”

This one-star general probably wasn’t the only American official who would have been surprised by Sjursen’s account. And the reason takes us back to Unlearned Lesson #2. According to Matthew Hoh, who served in Iraq as a Marine and in Afghanistan as a State Department official, the nearly complete absence of Pashtuns in the Afghan army was obscured by systematic misinformation.

“If you asked a general, if you asked an Afghan official, if you asked people in Washington DC, what percent of the Afghan army is Pashtun, they will say 40 percent [roughly the percentage of Pashtuns in the population at large],” says Hoh. He recalls being in a meeting with a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and talking about how few Pashtuns were in the Afghan army. “And one of his people, when I brought this up, she said, ‘No, he's wrong—the Pashtuns make up 40 percent of the Afghan army.’ Turns out, as we now know, the Pashtuns never made up more than three percent of the Afghan army.” (I had Hoh on my podcast 11 years ago, after he resigned from the State Department in protest of Afghanistan policy. Maybe if US officials had spent more time listening to him, and less time trying to undermine his credibility, this war would have ended sooner.)

Unlearned Lesson #4: We should try really, really hard to avoid military interventions.

This follows—not quite inexorably, but plausibly—from unlearned lessons 1, 2, and 3. If indeed (Lesson 1) the presence of foreign troops tends to energize and expand opposition; and if indeed (Lesson 3) this problem, along with other problems, is exacerbated by the difficulty of navigating ethnic and other social and political complexities—complexities that we tend to have only a dim comprehension of; and if indeed (Lesson 2) attempts to deepen that comprehension, and navigate these complexities, will be frustrated by the systematic corruption of relevant information—well, then maybe the odds against success are pretty steep. And since confirming how steep they are tends to get tons of people killed, maybe we should quit repeating that exercise.

Yeah all that. No more war.

Hi Bob, "America's longest war" is, well: What about the Indian wars? Say from 1776 to 1890? Or is each tribe/nation's defeat a separate war?

Lessons learned? Seriously? You sort of address this in your very good book 'THE MORAL ANIMAL' (1994, pgs 238-250) I highly recommend y'all give it a read. In Jared Diamond's book 'THE THIRD CHIMPANZEE' (1992) the epilogue is "Nothing Learned, and Everything Forgotten?" taken from a Dutch explorer and professor in 1912.

Like you, Diamond is "cautiously optimistic". If only ... . We have to be, right?

Looking forward to your GUT. cheers