Biden and Blinken, Israel’s Lawyers

Plus: Deepfake dupes senator, nuking asteroids, UK foreign secretary praises war crime, hawks flock at Hudson, liberate bottled water, and more!

This week President Biden, during his final address to the United Nations General Assembly, said the following about how the current conflict between Israel and Hezbollah began: “Hezbollah, unprovoked, joined the October 7th attack, launching rockets into Israel.”

This is only slightly misleading, but it’s misleading in an illuminating way—a way that helps explain Biden’s failure to end the carnage in the Middle East over the past year and also helps explain America’s failure to bring stability to the Middle East over the past few decades.

Here is how the year-long conflict between Israel and Hezbollah started:

Oct. 7: Hamas attacks Israel, intentionally killing many hundreds of civilians as well as hundreds of soldiers and police.

Oct. 7: Israel launches air strikes against Gaza, destroying numerous targets, including a mosque, and killing hundreds of Palestinians.

Oct. 8: Hezbollah strikes Israeli military posts in Shebaa Farms, a small, historically Lebanese patch of land that is not part of Israel under international law. Israel retaliates with strikes on Lebanon.

In the ensuing weeks and months, cross-border strikes on both sides expanded, and they have continued ever since.

Hezbollah explicitly said it struck Shebaa Farms as a show of sympathy with Hamas—so it’s fair for Biden to make a connection with October 7. Still, saying Hezbollah “joined the October 7 attack” makes it sound like Hezbollah collaborated in Hamas’s atrocities when in fact it’s unlikely that Hezbollah’s leaders even knew about the attack in advance, much less “joined” it.

Is this nitpicking? Here’s the case that it’s not:

1. Biden, as he spoke these words, was hoping that Bibi Netanyahu would sign on to a US-French proposal for a ceasefire between Israel and Hezbollah. Netanyahu is famous for resisting serious diplomatic engagement with adversaries, and he typically justifies this resistance by depicting them as the incarnation of evil. If Biden really wanted a ceasefire, why embrace the kind of exaggerated rhetoric Bibi had used to resist it? Wasn’t he making Netanyahu’s recalcitrance easier by endorsing its supporting narrative?

2. Netanyahu says he has escalated attacks on Lebanon so dramatically over the past two weeks because he must do “whatever it takes” to end Hezbollah’s missile fire so that Israelis evacuated from the northern part of the country can return to their homes. But, as Hezbollah has made clear all along, all it would take to end the firing of missiles into Israel is for Israel to end its war on Gaza. Biden’s description of the motivation for Hezbollah’s attacks obscures this conditionality and so, however slightly, reduces the pressure on Netanyahu to end the Gaza war, something Biden claims to want.

What’s more: Though the ceasefire with Lebanon proposed by the US and France would have entailed a ceasefire in Gaza, the attendant commitments would have lasted only three weeks—which means none of Israel’s stated reasons for resisting a longer Gaza ceasefire would apply. (Israel wouldn’t, for example, have to withdraw troops from the Philadelphi Corridor, between Egypt and Gaza.) Why, when Biden had the biggest megaphone available to anyone this week—the podium at the UN General Assembly—did he not convey how little the US and France were asking of Israel and so put some pressure on Netanyahu? Why did he do the opposite by describing Hezbollah’s attacks exactly as Netanyahu would have wanted?

Two decades ago, Aaron David Miller, a veteran US negotiator, lamented that American officials—including, he admitted, himself—had habitually acted as “Israel’s lawyer” rather than as an honest broker between it and its adversaries. He was referring to formal negotiations with the Palestinians, such as the Camp David talks of 2000, but the fact is that this basic tendency has infused American dealings with Israel more broadly. American presidents and their staffers, in describing Israel’s situation, reflexively parrot Israeli talking points. And, as Miller suggested, this doesn’t serve Israel’s long term interests (much less America’s interests) even if it does serve the political interests of whoever the prime minister is at the time.

Even over the past year, as Israel has killed 1 in 50 Gazans—and at least 1 in 100 Gazan civilians—the Biden administration, while saying it wants peace, has described Israel’s situation in a way that puts no pressure on Netanyahu to create it. A typical interaction with reporters by national security spokesman John Kirby or state department spokesman Matthew Miller involves reminding them that Hamas started the war, reminding them that Israel has a right to defend itself, and noting one or two ways Hamas is worse than Israel. Then, often, there is a ritual lamentation of “the suffering” in Gaza—as if “suffering” were some autonomous metaphysical force that mysteriously visits unfortunate parts of the world, rather than something delivered by bombs the US gives Israel.

This basic pattern has persisted for decades. The US gives Israel weapons, and it kills whoever it wants wherever it wants, regardless of the consequences for regional stability and regardless of any international or national laws violated in the process. And the US, like a good lawyer, describes the context for the attacks in ways that seem to justify them. Today’s Israeli strike targeting Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, which brings the Middle East appreciably closer to full-scale regional war, is in part the product of many years of this kind of positive reinforcement.

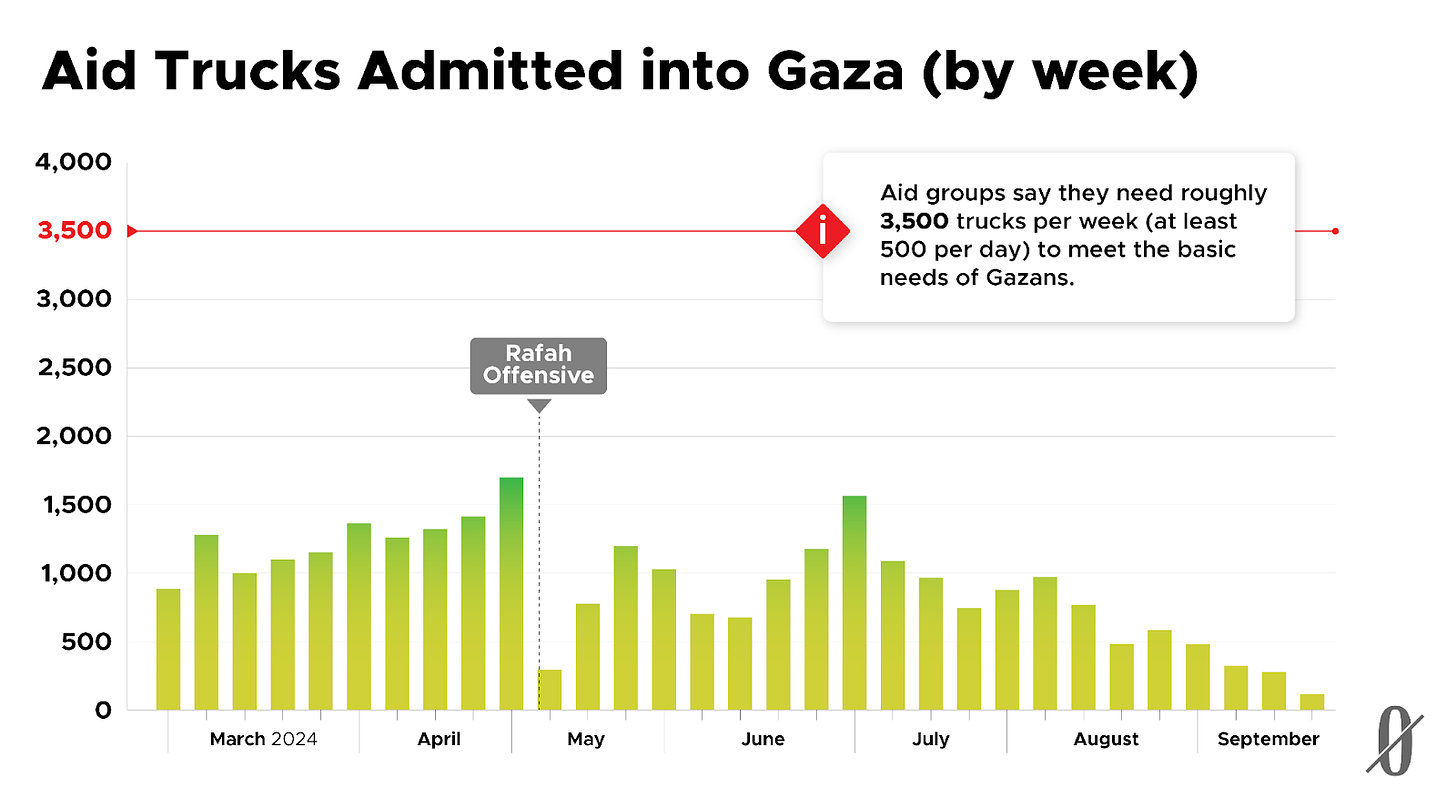

Speaking of national laws that get sacrificed in the name of Israel: This week ProPublica reported that, back in April, Secretary of State Antony Blinken ignored two Biden administration reports finding that Israel was blocking US aid from getting into Gaza—findings that, according to US law, should have led Washington to end weapons exports to Israel. The reports came from USAID and the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration, the government’s leading authorities on humanitarian aid. Though Blinken was aware of both reports, he chose to certify Israel’s compliance with the law, telling Congress in May that “we do not currently assess that the Israeli government is prohibiting or otherwise restricting the transport or delivery of US humanitarian assistance.”

This, according to Sarah Harrison, a former Pentagon lawyer, was par for the course. “This was my experience in government,” she wrote. “If bureaucrats determined Israel’s actions triggered US law restricting the transfer of arms, political leadership would ignore them. It didn’t matter that the civil servants writing the memos were the most informed on these issues.”

Blinken’s decision came at a critical moment. Israeli forces had just seized a crossing in the southern city of Rafah, closing a key entry point for humanitarian aid. The Biden administration hoped to stop a full-scale assault on Rafah, where many displaced Gazans had sought refuge. But Blinken’s statement amounted to a green light for Israel, and four days later Israeli forces began an offensive that displaced one million Gazans and damaged or destroyed more than 40 percent of the buildings in Rafah.

As hostilities in Lebanon escalated this week, some friends of Israel expressed grave concern. (Check out the levels of alarm and despair in this Tom Friedman column.) That’s not because Israel may “lose” the war. Indeed, its military dominance over all regional enemies has now been demonstrated so thoroughly as to undermine its description of them as existential threats. If there’s an existential threat to Israel, it’s a much longer term threat, and its seeds lie in Israel’s reflexive preference for short-term military victory over far-seeing diplomacy. Nobody has done more to encourage and reinforce that reflex than Israel’s American lawyers—including, most recently, Joe Biden and Antony Blinken.

They may be blissfully unaware of this paradox, but this week we found out that there’s at least one headline writer at the Washington Post who isn’t numb to irony: “Biden touts his record at U.N. as Mideast violence erupts.”

This week, the NonZero Newsletter did something it’s never done before: published a solo piece by someone not named Bob. The article, written by NZN managing editor Connor Echols, dives deep into the worldview of Alex Karp, the eccentric CEO of surveillance giant Palantir. Connor argues that Karp is the quintessential example of a new breed of military contractor—one part Silicon Valley tech optimist and one part Beltway hawk. And he argues that this species of hawk may speed up humanity’s demise.

NZN members can read the full, 2700-word profile here. Here’s a preview:

By 2013, Karp had become a darling of the national security state. Gen. David Petraeus met Karp while serving as CIA director and came away dazzled. “He’s not tailored, shall we say. And he doesn’t care,” Petraeus told Forbes. “He’s thinking deep thoughts.” George Tenet—another former CIA director—was also a fan. “The guy’s an absolute mensch,” Tenet has said, “and you can trust him with your life.”

In the following years, when a series of massive terror attacks shook Europe, authorities used Palantir's tech to help tame the upsurge in violence. This contributed to Karp’s sense that he stood between the West and its possible collapse into authoritarianism. “We changed the course of, especially, European history,” he has boasted, “by making it possible to stop terrorism in accordance with democratic norms.”

You can expect to see more of these non-Earthling issues of the NonZero Newsletter in the coming weeks and months as NZN expands its offerings and assumes its rightful role as a global media juggernaut (or closer to that than it is now). If you’re not feeling inspired to read the full profile, we would still suggest that you check out the accompanying image, created by NZN artist-in-residence Clark McGillis.

Nuclear weapons could save Earthlings from a life-obliterating calamity, according to findings published in Nature Physics.

Physicists at Sandia National Laboratories in New Mexico simulated the nuclear deflection of an approaching asteroid and reported success. They fired X-rays—which emanate from nuclear explosions—at coffee-bean-sized mock asteroids that were free-falling in a vacuum. The X-rays vaporized the surfaces of the “asteroids,” generating gas that pushed them off their trajectories.

This isn’t the first time scientists have explored the salvific potential of space nukes. Previously, researchers had examined the possibility that shock waves from nuclear bombs could help redirect asteroids. But the Sandia scientists say X-rays are better suited to the job; they don’t require a medium for their transmission and so travel well in outer space—which means the nuke could detonate far from the asteroid and thus avoid blowing it into lots of dangerous smithereens.

Still, all things considered, we humbly offer one suggestion: When the scientists take their experiment into outer space and fire X-rays at a real, non-coffee-bean-sized asteroid, which they hope to do, please perform the tests a long way from planet Earth.

Some of America’s most esteemed militarists gathered at the Hudson Institute Thursday to discuss their vision for the “new cold war.”

While the first Cold War focused largely on Russia, the folks at Hudson are daring to dream bigger—much bigger. This time around, Uncle Sam’s enemy is a “quartet of evil” composed of China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia, argued Morgan Ortagus, a conservative radio host and former spokesperson for Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. Ortagus said these states have come together to create a “supply chain of terror” that empowers their nefarious pursuits.

Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.) said the only way to counter a threat so vast is to do away with the “faulty” idea that “we can seal off and compartmentalize a conflict in one place of the world.” To deter each player in this quartet of doom, we must push back against all of them, everywhere, all at once, he argued.

Of course, the more major enemies you have, the harder it is to follow the cold war tradition of lumping them under a single malign ideology. Joe Lonsdale, a Palantir co-founder and defense tech investor, said America now faces the dual threats of communism and Islamism. (Palantir CEO Alex Karp, whom NZN profiled this week, seems to be on more or less the same page.) The battle against these ideologies begins at home, Lonsdale argued; the first regime to be toppled is American bureaucracy, with its legions of busybody regulators who hamper the efforts of patriotic defense tech investors.

Cotton concurred. America is “running out of time” to deter China from invading Taiwan, he said—and the way to fix that problem is to cut through red tape, boost military spending, and, more broadly, reorient the US economy toward national defense.

But that leads to a problem: Giving more money to the military is a controversial policy in a country that already has an $820 billion defense budget, the largest in the world. So how might these new cold warriors bring Americans around to their perspective? They can start by taking a page from the old Cold War playbook, argued Palantir CTO Shyam Sankar, who praised his 1950s-era forefathers for bravely deciding to “kind of stretch the truth about the ICBM threat from the Soviets” in order to persuade Congress to fund America’s own ballistic missile programs.

In a subsequent panel, Mackenzie Eaglen—a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute—did her part. While most analysts agree that Beijing spends far less than Washington on its military, Eaglen said China’s real defense budget is “higher than $700 billion.” There—problem solved.

Scientific American magazine made a big mistake by endorsing Kamala Harris for president, writes Tom Nichols of The Atlantic.

That’s not to say that Nichols—a vociferous Trump critic—wishes the magazine had endorsed her opponent. Rather, he argues that “a magazine devoted to science should not take sides in a political contest.” (Though Scientific American has long weighed in on policy issues related to science, this is only the second candidate endorsement in its 179-year history. The first was its 2020 endorsement of Joe Biden.)

Nichols doubts that Scientific American’s endorsement will change how readers vote, but he does think it could undermine their trust in the magazine. He points to a 2021 study in which researchers showed Biden and Trump supporters descriptive material about the journal Nature that included sample text from it. One version of the material highlighted the journal’s 2020 endorsement of Biden. Trump supporters who saw that version were substantially less trusting of Nature and somewhat less trusting of the scientific community as a whole. Biden supporters who saw that version were more trusting of Nature, but the effect was relatively small. Nichols writes:

“If the point of a publication such as Scientific American is to increase respect for science and knowledge as part of creating a better society, then the magazine’s highly politicized endorsement of Harris does not serve that cause.”