Biden takes the bait in Yemen

Plus: New plastics peril, AI versus global-warming-boosted superbugs, America versus America, Putin’s precarious popularity, and more!

On Thursday, shortly before the US launched airstrikes against Houthi targets in Yemen, political scientist Gregory D. Johnsen was discussing the Houthi leadership’s perspective in an interview with Mark Leon Goldberg of the Global Dispatches Newsletter. Johnsen, who specializes in Yemen, said that if Houthi leaders can “say that they're defending Palestinians by carrying out attacks on shipping in the Red Sea—but also bait the United States, Israel, the UK, anybody, into firing airstrikes into Yemen—then the Houthis think that they can come out as victors.”

Now that President Biden has taken the bait, it’s worth explaining what Johnsen meant—because the upshot is that these airstrikes, even if repeated again and again and again, are not going to stop the Houthis from attacking ships in the Red Sea. If Biden wants to achieve that goal, and step back from the slippery slope toward regional war, he needs to use America’s considerable leverage with Israel to stop the fighting in Gaza. And one reason there’s no substitute for applying that leverage forcefully is that Bibi Netanyahu and the Houthi leadership have something in common: Both gain politically from continued conflict, even if that conflict isn’t in the interest of the people they supposedly serve.

It’s common to view the Houthis as proxies of Iran, and certainly Tehran supports their policy of disrupting commerce in the Red Sea until the fighting in Gaza stops. But as Johnsen (whom I interviewed in 2011 on bloggingheads.tv, the precursor of the Nonzero Podcast) explains, this policy would make sense for Houthi leaders in any event. That’s partly because it elevates their stature in the Arab world, but also because it solves, for the time being, a big problem: As their war with Saudi Arabia has wound down, the domestic support they were getting via the rally-round-the-flag effect has waned, and they’ve discovered that governing a fractious country is hard.

Johnsen says, “They've found that there's been more domestic unrest and more domestic challenges now than there were during the height of the war” (a war, by the way, that featured American logistical support for the relentless and massively lethal Saudi bombing of Yemen). The Houthis’ confrontation with the West in the Red Sea has helped subdue these challenges, and Houthi leaders expect western airstrikes to help even more. “They think they will gain a lot of domestic support and there will be another rally-around-the-flag effect,” says Johnsen.

But aren’t the Houthis worried about the devastation American firepower could wreak? Johnsen says:

Remember: the Houthis are an organization that survived nearly a decade of war with Saudi Arabia and the UAE. They're still around. They've survived airstrikes in the past. And in fact, as bad as airstrikes have been for the country of Yemen, politically, they've been pretty good for the Houthis… Short of a military confrontation the scope and scale of which I don't think the Biden administration, or frankly the American people, would be comfortable with, I don't think anything would deter the Houthis.

Johnsen says he’s not sure a ceasefire in Gaza would stop the Houthis’ attacks on Red Sea shipping, now that their showdown with the US has moved to center stage and the US has killed Houthis (first by sinking three Houthi attack boats two weeks ago, and now in the airstrikes that took place shortly after Johnsen spoke, which were known to be eminent at the time he spoke). “After Houthi militiamen have been killed, after the Houthis have seen how much impact this has on the United States, this particular tactic that the Houthis are utilizing is going to be very hard for them to walk away from.”

On the other hand, the Houthis’ repeated assertion that their Red Sea attacks are retaliation for Israel’s war in Gaza, and can stop when the war stops, would make continuing the attacks after the war ends kind of awkward. And Iran—which wants Israel’s decimation of Hamas to end and doesn’t want to get engulfed in a wider war—would presumably push the Houthis to stand down if the fighting in Gaza stopped.

As for whether the US has the leverage to push Israel toward a ceasefire and then a war-ending deal: Well, there’s that quote from Israeli Major General Yitzhak Brick that you may recall from last Friday’s NZN: “All of our missiles, the ammunition, the precision-guided bombs, all the airplanes and bombs, it’s all from the US. The minute they turn off the tap, you can’t keep fighting… Everyone understands that we can’t fight this war without the United States. Period.”

Biden clearly doesn’t want to use this or the other big levers he could use with Israel. He keeps saying that he’s working quietly, behind the scenes, to moderate Israel’s behavior. But quiet cajoling is unlikely to end the Gaza war, because Bibi Netanyahu has an even stronger domestic political incentive to keep fighting than the Houthi leaders have. It’s widely agreed in Israel that once this war ends, Netanyahu will have to step down, owing to, among other things, the incompetent governance that made the devastating scale of the October 7 attacks possible. For Bibi, the best war is a forever war.

In sum: Both Israel and Yemen have leaders who benefit politically from war, and Biden seems determined to accommodate both of them, notwithstanding the fact that this accommodation is visiting mass death and suffering on Gazan civilians, damaging American interests (and, as most sober observers recognize, Israel’s interests), and leading the Middle East toward a wider and possibly catastrophic war.

Why is Biden doing this? Hard to say for sure, but the political incentives for any American president to do what Israel wants are strong, and one thing Biden has in common with Netanyahu and the Houthi leaders is that he’s a politician. Every once in a while a nation gets a leader whose wisdom and courage transcend crass political calculation, but Israel, Yemen, and the United States are three nations that don’t have that kind of leadership right now. —RW

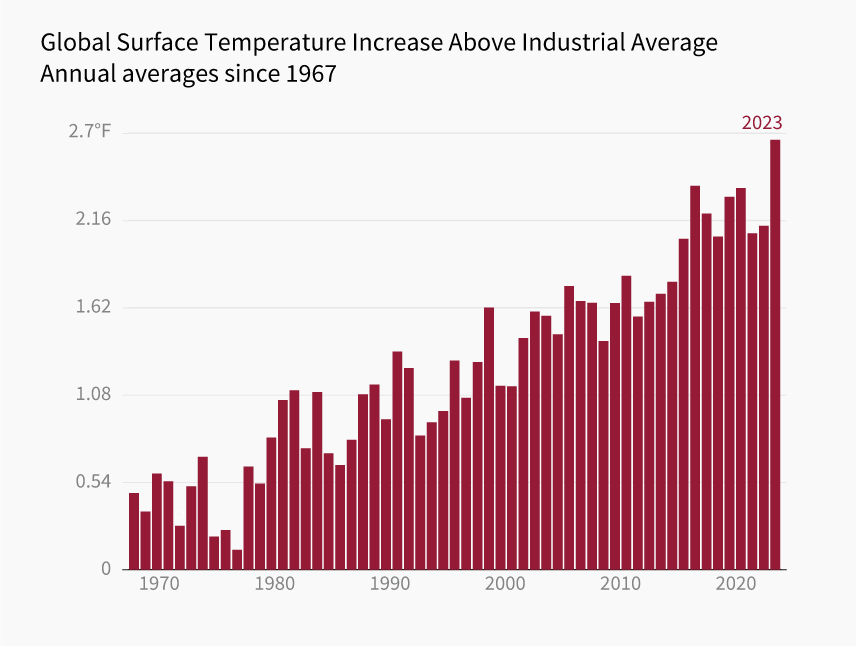

The New York Times reports that 2023 was a warm year—“Earth’s warmest by far in a century and a half,” according to numbers released this week by the European Union’s climate monitor.

One side effect of climate change: swollen tonsils. In Nature, reporter Carissa Wong writes that rising temperatures encourage the growth of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, though scientists aren’t sure why. (Maybe hot weather leads people to stay inside, where bacteria spread more easily, and this prolific replication increases the chances of resistance-conferring mutations.) The problem of drug-defying superbugs will be discussed at the UN’s antimicrobial resistance conference this September, the second conference of its kind.

Meanwhile, some good news: Last month scientists reported in the journal Nature that they’d used artificial intelligence to discover a new class of compounds that are effective against antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

The Eurasia Group released its Top Risks report for 2024. The report highlights ten risks, but, in hopes of keeping your stress level manageable, we’ll mention only three:

Ungoverned AI: “Gaps in AI governance will become evident in 2024 as regulatory efforts falter, tech companies remain largely unconstrained, and far more powerful AI models and tools spread beyond the control of governments.”

Middle East on the brink: “…Hamas’s terrorist attacks shook the region to its core, jolting the world out of its sense of complacency on the Palestinian issue, shattering Israel’s sense of security, and turning the Middle East into a powder keg.”

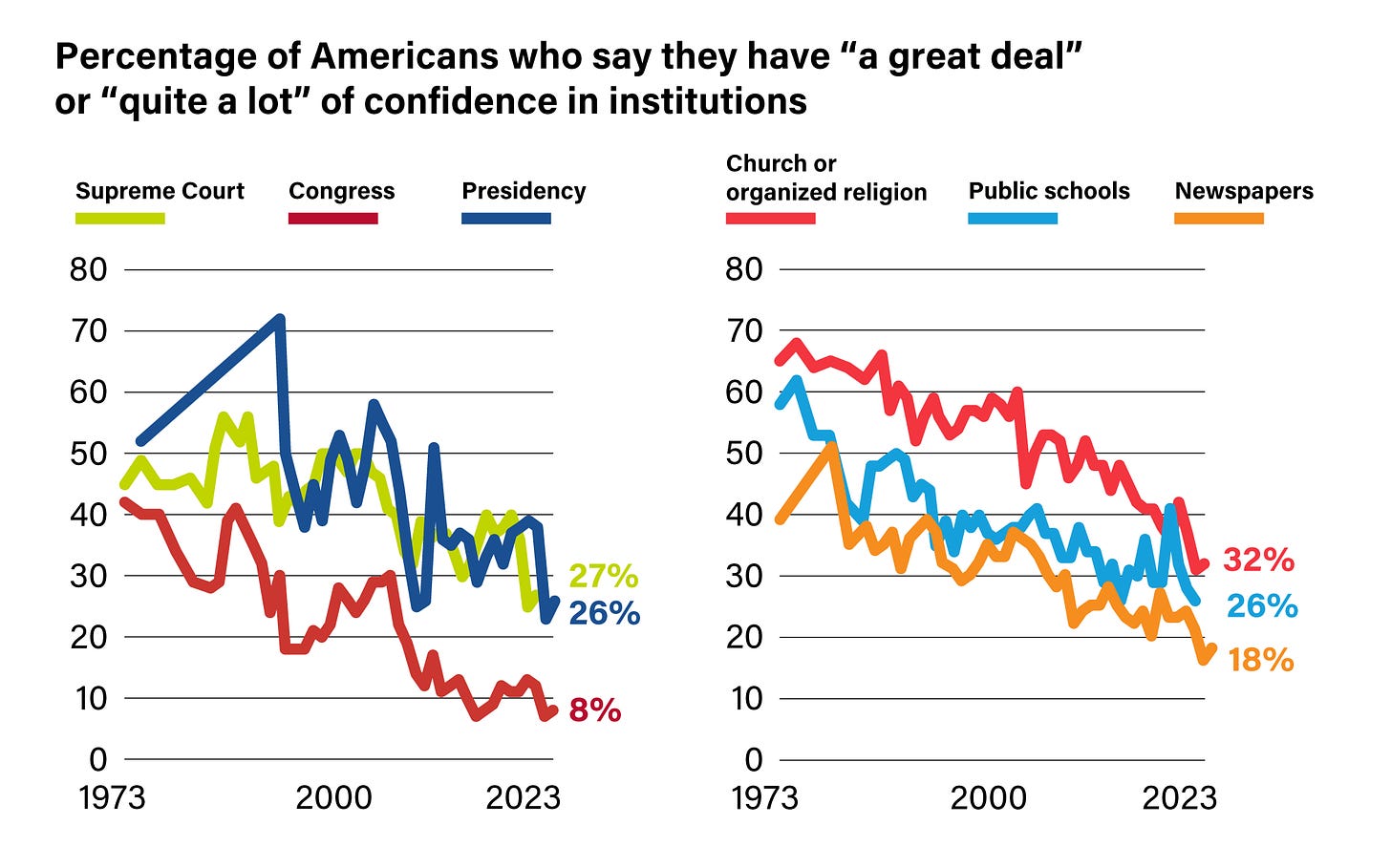

The United States vs. itself: “The US presidential election will worsen the country's political division, testing American democracy to a degree the nation hasn't experienced in 150 years and undermining US credibility on the global stage.”

The write-up of that last risk came with a series of charts illustrating Americans’ plummeting confidence in the country’s political and social institutions. NZN graphics czar Clark McGillis combined and adapted the charts, creating NZN’s graphs of the week: