Biden’s Tough Love Deficit

Plus: Chatbots gone wild. Blob-sponsored Russia space nukes freak-out. Trouble in the Taiwan Strait. Is a green Earth good? Gaza war unites Middle East. What Navalny meant. And more!

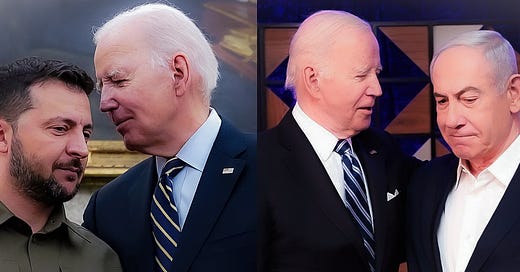

As of this weekend, it’s been exactly two years since Russia invaded Ukraine and exactly 20 weeks since Hamas attacked Israel. There are lots of differences between those two events and between the wars they’ve brought, but there’s one important commonality: how President Biden has reacted. In both cases he has come to the aid of a friend in need and done so in a way that wasn’t ultimately good for the friend. Biden is good at showing love and catastrophically bad at showing tough love.

With both Ukraine and Israel, the US has massive leverage—by virtue of being a critical weapons supplier and also in other ways. And in both cases Biden has refused to use the leverage to try to end wars that are now, at best, pointless exercises in carnage creation.

In the case of Israel, that refusal is so well known as to require no elaboration. (Even the European Union’s foreign minister has subjected Biden to borderline ridicule for calling Israel’s conduct in Gaza “over the top” while keeping the weapons flowing.) What may require elaboration—given that Gazans are dying en masse and Israelis aren’t—is my claim that Biden’s blank check to Israel is bad for Israel.

But it’s hard to see how the slaughter being visited on Gaza won’t come back to haunt Israel. Hundreds of thousands of Gazans—out of a total population of 2.1 million—now have close relatives who have been killed or maimed by Israel. That’s enough hatred to fuel violence against Israelis for decades. Israel says all the killing is necessary so it can “eliminate” Hamas—as if (assuming such elimination is even possible) the specific brand under which hatred is converted into violence is the big issue.

Of course, there’s a chance that Israel will insulate itself from much of this hatred—that the war will end with the ethnic cleansing of Gaza or with an Israeli occupation of Gaza so brutal as to suppress all resistance. And maybe Bibi Netanyahu would call both of these things a win.

And, actually, by the political calculus that has governed his career, they might be. After all, in one case Israel would face something close to global ostracism, and in the other case intense and sustained international criticism, and in neither case would the Palestinian conflict be resolved. So Israeli politicians who thrive on the country’s sense of insecurity and of persecution—political assets Bibi has carefully cultivated for the past two decades—would be sitting pretty. But Israel itself wouldn’t be.

In the case of Ukraine, Biden’s failure to use his leverage to push an American friend toward peace hasn’t been a topic of much discussion. After all, only in the last few weeks, as battlefield momentum has clearly shifted toward Russia, has it occurred to many Americans that ending the war is in Ukraine’s interest even if Russia continues to occupy Ukrainian territory. And even now a widespread assumption is that if only Congress will cough up the money for another round of weapons, all will be fine.

But all won’t be fine. Ukraine will run out of soldiers long before Russia does, and Russia’s industrial capacity means that its ongoing supply of weapons, unlike Ukraine’s, is enduringly insulated from the unpredictable politics of other nations.

Such basic asymmetries have been obvious for a long time to the handful of American foreign policy elites who are capable of soberly assessing Russia-related phenomena. Fifteen months ago Gen. Mark Milley, then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told the Biden White House that Ukraine’s battlefield position was unlikely to significantly improve and could deteriorate, so it was time to talk peace. (A month later I wrote a piece for the Washington Post—which also appeared in NZN—arguing that, “If indeed Zelensky’s reluctance to negotiate is partly a product of political pressure, Biden would be doing him a favor by playing the heavy and pushing him toward the negotiating table, shielding him from the political fallout. Biden would also be doing Ukraine a favor.”)

Today, 15 months after Milley’s warning, Ukraine’s battlefield position is much more precarious and its negotiating position accordingly weaker. And there are now tens of thousands more dead Ukrainian soldiers, and tens of thousands more Ukrainian amputees, than there were when Milley tried to stop the bloodshed.

Milley’s effort to inject reason into US foreign policy discourse was overcome by the usual suspects—the Michael McFauls and Anne Applebaums of the world, zealous hawks who, notwithstanding their track records, have open invitations to America’s dominant media platforms. Biden sided with them against Milley, agreeing that we had no right to question the judgment of Ukrainians—our friends, after all—who wanted to expel Russian troops from all Ukrainian territory at all costs. So, 15 months later, Ukrainian “agency” is alive and well, even if many fewer Ukrainians are.

For better or worse (mostly worse), America’s foreign policy is organized largely around the goal not just of keeping America a superpower, but of keeping it the world’s dominant superpower. But what’s the point of being a superpower if you don’t use your power when it’s really needed?

And I have one more Biden-related question: Is it too late to make Mark Milley a candidate for president?

This week, ChatGPT users reported that the bot was going haywire, in some cases babbling incoherently or speaking Spanglish. Some observers said the episode demonstrated the need for improving AI transparency and interpretability. “Really cool how the most advanced AI systems can just randomly develop unpredictable insanity and the developer has no idea why,” said AI safety advocate Connor Leahy. “Very reassuring for the future.” OpenAI later blamed the chatbot’s “unexpected responses” on a software bug that had since been fixed.

Shortly after ChatGPT regained its senses, its big rival, Google Gemini, started having problems of its own. Asked to generate images of, say, America’s founding fathers, or of a pope, Gemini seemed reluctant to depict white males. Accusations of hyper-wokeness ensued, and Google responded by taking its image generator offline, pending recalibration.

Some observers sympathized with Google’s effort to accommodate an ethnically diverse world. When users ask for images of, say, children roller skating, you don’t want all the pictures to look like they came from an American first grade reader circa 1960. And when more than a fourth of Sweden’s population was born abroad or has foreign-born parents, you shouldn’t expect a “Swedish women” prompt to yield only blondes. But even Google defenders conceded that the company had done a ham-handed job of inclusiveness.

And some had a darker takeaway. Yishan Wong, former CEO of Reddit, said that, like the famous paper-clip maximizing thought experiment, Google’s snafu illustrated the difficulty of avoiding unforeseen AI consequences, including catastrophic ones. Wong was reminded of Isaac Asimov stories in which robots would “do something really quite bizarre and sometimes scary, and the user would be like WTF, the robot is trying to kill me, I knew they were evil! And then Susan Calvin would come in, and she’d ask a couple questions, and explain, ‘No, the robot is doing exactly what you told it, only you didn’t realize that asking it to X would also mean it would do X2 and X3.’”

Meanwhile, in the Great White North, the well known tendency of bots to hallucinate recently created some turbulence for Air Canada. A customer named Jake Moffat had gone to the airline’s website to book a flight so he could attend his grandmother’s funeral. There, a bot told him he could get a bereavement discount so long as he requested it within 90 days. When he followed that guidance, Air Canada denied the discount, noting that their policy requires bereavement discount requests to be submitted before booking. Moffat sued, and, though the airline argued that "the chatbot is a separate legal entity that is responsible for its own actions," the judge ruled in his favor.

China-Taiwan tensions are rising in the Taiwan Strait. And the friction is happening around land where armed conflict erupted twice during the Eisenhower era: the Kinmen (also called Quemoy) islands—which, though Taiwanese territory, are more than 100 miles from Taiwan and barely more than a mile from China’s coast.

This week, China’s coast guard intercepted a Taiwanese tourist boat that was traveling around the islands and spent half an hour inspecting it. According to a CNN report about the interception, it was “meant to provoke” Taiwan and cause “panic” there.

But Beijing may see itself as provoked. A week earlier, Taiwan’s coast guard chased down a Chinese vessel near the same islands after it allegedly entered Taiwanese water. The boat was operated by Chinese fishermen, two of whom drowned after it capsized during the chase. China’s coast guard then ramped up patrols around the islands.

There’s another recent development that Beijing may consider provocative. Earlier this month, Taiwanese media reported that US military advisers had been deployed to Kinmen on a long-term basis.

Because the US has deployed special-ops trainers in Taiwan since at least 2020, some China watchers said the news was overblown. But this is the first time the presence of US troops in Kinmen—right on China’s doorstep—has been confirmed. And after President Biden signed a budget bill in December that formalized and expanded the military training of Taiwanese forces, Chinese officials and analysts condemned the new law as a threat to China’s security.

America could be “facing this generation’s Sputnik moment,” according to a New York Times op-ed. This reference to 1957, when the USSR’s launching of the world’s first orbital satellite jolted America into the space race, was occasioned by reports that Russia may be trying to put a nuclear weapon into outer space.

Or may not be. As the media’s breathless coverage of this story unfolded, it became less and less clear what Russia was actually up to.

On February 14 the New York Times had reported that a Russian space-based nuclear weapon, “if deployed, could destroy civilian communications, surveillance from space and military command-and control operations by the United States and its allies.”

Then three days later we learned from a Times follow-up piece that “any nuclear detonation in space would take out not only American satellites but also those in Beijing and New Delhi.” Which raised the question of why Russia would contemplate using such a weapon unless it wanted to go through World War III with zero allies.

Then came a third Times piece suggesting that Russia’s own satellites would also be imperiled by a nuke in space. The mystery surrounding Russia’s strategic calculus deepened. Until you got to this part of the Times piece: