Biden’s Ukraine quagmire

Plus: Sun-blocking space umbrella, Cold War II goes to Africa, down with climate doom, AI-boosted brain-chips, how economic decoupling makes WWIII more likely, and paid subscriber perks.

This week a widely followed Twitter account called War Mapper quantified the amount of terrain Ukrainian forces have retaken since the beginning of their counter-offensive two months ago. The net gain is a bit over 100 square miles. So the fraction of Ukrainian territory occupied by Russia has dropped from 17.54 percent to 17.49 percent.

This gain has come at massive cost: untold thousands of dead Ukrainians, untold thousands of maimed Ukrainians, and lots of destroyed weapons and armored vehicles.

At this rate of battlefield progress, it will be six decades before Ukraine has expelled Russian troops from all its territory—the point before which, President Zelensky has said, peace talks are unthinkable. And at this rate of human loss, Ukraine will run out of soldiers long before then—and long before Russia does.

In short: Recent trend lines point to a day when Ukraine is vulnerable to complete conquest by Russia. For that matter, the counter-offensive has already made Ukraine more vulnerable to a Russian breakthrough in the north, where Ukrainian defensive lines were thinned out for the sake of the offensive in the south. Russia has been gaining ground in the north incrementally, and a big breakthrough would let it retake parts of Kharkiv province that it lost last September.

Of course, a breakthrough by Ukraine in the south could also lead to big gains. But there are multiple Russian defensive lines to breach before achieving the offensive’s goal of severing the Crimean “land bridge.” And the chances of doing that before the autumn muddy season gives Russia a chance to regroup are looking slim.

So what is Ukraine’s long term plan? A clue comes from another widely followed Twitter account, Tatarigami_UA. It’s run by an astute Ukrainian reserve officer—someone who seems roughly as knowledgeable as people in Ukraine’s defense establishment but speaks with more candor than they can afford.

In a thread posted earlier this week, Tatarigami spent several tweets establishing, via satellite images, that the Russians have more ample reserves of armor than many believe—so “statements insinuating that they are almost depleted of equipment are not accurate.” Which raises the question: If Russia doesn’t face a near-term armor shortage, and its munitions factories have moved to a wartime footing, and its human resources vastly exceed Ukraine’s, where does hope lie for the complete Ukrainian victory that Kyiv continues to insist on?

Here is Tatarigami’s answer: “Considering Russian political instability, exemplified by the Wagner mutiny, I am inclined to think that a potential power collapse and internal struggle among elites, driven by military defeats, will let us liberate all occupied territories.” But since “predicting the number of defeats needed for the regime's collapse is nearly impossible, we must simply concentrate on continuous military defeats of Russians.”

The resolve is admirable. But have things really come to this? We’re throwing Ukrainian men into a meat grinder week after week in hopes that maybe Putin’s regime will collapse, and maybe this will be good for Ukraine? Even though regime collapse could well bring to power a more intensely nationalist leader who would mobilize hundreds of thousands or even a million fresh Russian troops? And even though regime collapse could also lead to civil conflict and chaos within Russia, a nation full of nuclear weapons? And even though the prelude to collapse could find Putin desperate for battlefield gains to stave off domestic pressure from the right, and maybe even pondering the use of tactical nuclear weapons?

If President Biden welcomes the prospect of regime collapse in Moscow, he lacks the prudence a president should have. Nor should he welcome Ukraine’s other main hope for evicting Russian troops from its territory: getting NATO involved in the war—something that Zelensky understandably hopes for, and something that grows more likely as the war continues, but something that could lead to a regional conflagration or even nuclear war.

So maybe it’s time for Biden to push Zelensky toward peace talks? Apparently not. According to the Wall Street Journal, “western officials” say that the meager results of Ukraine’s counteroffensive are “dimming hopes” for negotiations, because Biden had planned to “negotiate with Russia from a position of strength” after the offensive, and that’s not the position Ukraine seems headed for.

Yet back when Ukraine was in a position of strength—after last year’s battlefield successes in Kharkiv and Kherson—suggestions that Biden talk peace (made by Joint Chiefs Chairman Mark Milley among others) were widely dismissed on grounds that you shouldn’t negotiate when things are going well on the battlefield—when “the wind is at our back” (which, predictably, the wind turned out not to be for very long).

In short: We can’t talk peace from a position of strength or of weakness, or from points in between. So we’ll wait for the Putin regime’s collapse or for NATO to enter the war—and hope that neither of those brings the regional if not global catastrophe that either could well bring.

Does that summarize Biden’s current thinking? If not, could somebody explain what he is thinking? What is his plan? How does he intend to explain to Americans in six months, nine months, a year, why he’s still spending billions of their tax dollars to sustain a bloodbath that seems to be accomplishing nothing except the destruction of Ukraine?

Donald Trump says that if he wins the 2024 election he will push Ukraine toward a peace deal and threaten Putin with intensified support of Ukraine if Moscow doesn’t accept the deal. That’s easier said than done, but at least it shows an understanding of America’s leverage with both Ukraine and Moscow—an understanding Biden either lacks or is for some reason reluctant to evince.

The latest New York Times presidential election poll shows Trump tied with Biden at 43 percent. It’s not inconceivable that in 14 months the Ukraine war could put Trump, who spent the waning months of his presidency trying to subvert the US constitution, back in the White House. In which case the man who performed the great service of evicting Trump from the White House will be partly to blame.

Attention NZN members! Be sure to check out these paid subscriber perks:

The latest edition of Earthling Unplugged, Bob’s conversation with NZN staffer Andrew Day about all the items in the latest Earthling, as well as a few stray thoughts.

The latest edition of the Parrot Room, Bob’s after-hours conversation with Mickey Kaus. You can find the episode, along with Earthling Unplugged, in your paid-subscriber podcast feed. (To set that up, just go to the Earthling Unplugged link above, click “Listen on” on the audio player, and follow the instructions.)

“Decoupling”—reducing economic engagement with China and Russia—has over the past few years become a fact of life in the West. In Foreign Affairs, Ali Wyne of the Eurasia Group highlights a downside of this disengagement: It makes conflict more likely.

Decoupling gained momentum after the Covid pandemic highlighted one downside of interdependence: the West was reliant on China for medical supplies and other imports that were no longer guaranteed to flow. Then Russia’s invasion of Ukraine drew attention to the leverage Putin had by virtue of Europe’s dependence on Russian oil and gas.

But, Wyne writes, that’s only half the story. By increasing the costs of aggression, interdependence forces states to think twice about hostile behavior. In a world with less economic engagement, “Beijing and Moscow could become less fearful of contesting Western influence and more likely to deepen their partnership, especially if they are able to bolster ties with nonaligned powers and countries across the developing world.”

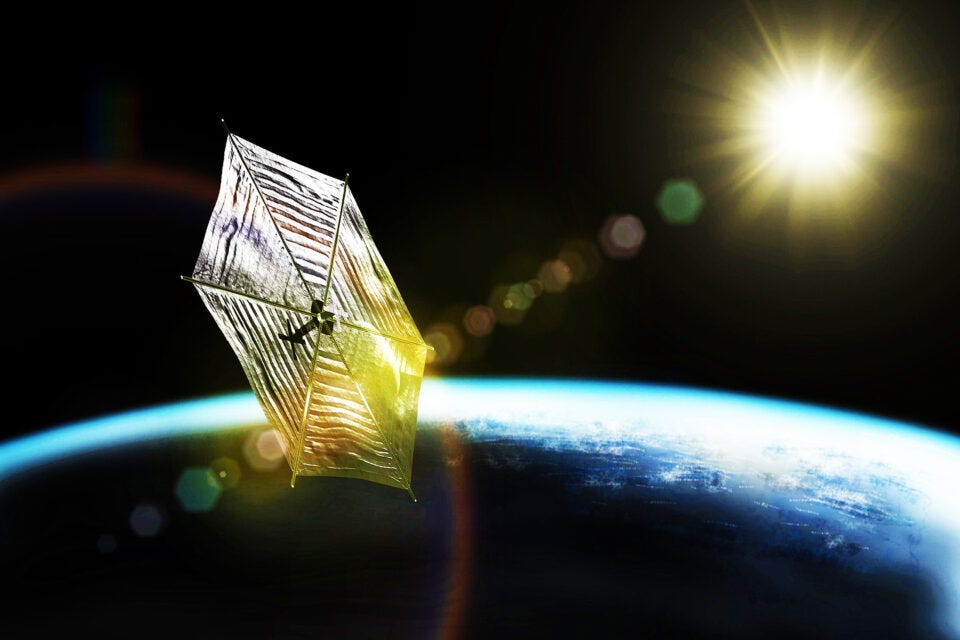

In the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, astronomer Istvan Szapudi of the University of Hawaii offers this extremely ambitious strategy for mitigating global warming: Put a big umbrella in outer space.

You may wonder: