I have big news (seems big to me at least) about my future and the future of this newsletter—and about the connection between the two.

1) I’m about to start writing a book. I know, I know—I said this once before, and a book failed to materialize. But this time I signed an actual contract, and my record for writing books when failure to do so could get me sued for recovery of funds is five for five.

2) I’m about to embark on a bold and exciting experiment in making a newsletter part of the process of writing a book. Actually, “bold and exciting” may turn out to be an exaggeration. But it may not! What’s about to happen in this newsletter is in some ways a mystery to me. But it’s definitely going to be an experiment, and right now it feels pretty bold and exciting. Scarily so, in a way.

Before I talk about the experiment—which officially begins next week—a word about the book:

This book won’t be called The Apocalypse Aversion Project, the title of the book I said I’d write and never wrote (though—credit where due!—I did write the draft of an introductory chapter). But this book is definitely part of the Apocalypse Aversion Project—a central part, in fact. The subject of the book is a skill I consider critical to keeping the world from entering the grim downward spiral that I loosely refer to as the apocalypse.

I’ll pause now while regular NZN readers guess which skill I’m talking about…

Correct! The skill I’m talking about is cognitive empathy. For non-regular readers: That’s not the feel-their-pain kind of empathy, which is known as emotional empathy, but rather the comprehend-their-point-of-view kind of empathy. I maintain that if we could cultivate this skill broadly—make lots of people better at understanding how things look from perspectives different from their own—prospects for the world’s salvation would brighten dramatically.

The working title of the book (and in my experience working titles have a one in five chance of becoming actual titles) is The Radical Power of Cognitive Empathy. The publisher is Simon and Schuster, with whom I had a great collaboration on my last book, Why Buddhism Is True.

The book will be broader in scope than you might guess from reading this newsletter. In the newsletter I’ve focused mainly on political applications of cognitive empathy—on how, for example, adroitly exercising cognitive empathy could prevent wars or help end them, and how it could keep America from descending into deeper and more bitter polarization. But cognitive empathy has lots of other uses, including at work and at home and in society at large. And it has philosophical, even spiritual, dimensions I’ve barely explored in the newsletter.

This breadth is good news for you, I think, because it means that the newsletter can reflect—and advance—my progress on the book without becoming monotonous. In fact, this book-newsletter synergy experiment will probably make the newsletter less monotonous. In recent months I’ve been pretty preoccupied with the aforementioned applications of cognitive empathy in the realms of international conflict and intranational conflict. And, while I’ll certainly continue to write about these things, working on the book will push me to broaden my vision.

Which leads to the big question: How exactly will the newsletter reflect and advance my progress on the book? What is this “bold and exciting experiment” I speak of?

First, I want to be clear about the model of book-newsletter synergy this project will not follow: I won’t be regularly publishing excerpts of the book behind a paywall. That’s not because I don’t like paywalls—in fact, a fair amount of this experiment will be accessible only to paid subscribers, and if you’re not one of those I of course encourage you to remedy that tragic situation asap:

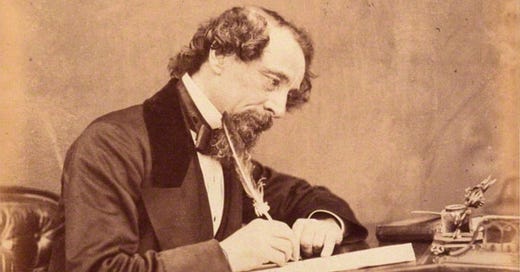

Rather, the reason I won’t be following the regular-publication-of-excerpts-behind-paywall model is that I won’t be regularly publishing excerpts at all. There are people who are good at publishing excerpts of a work-in-progress regularly. Like Charles Dickens. His novels came out first in serial form, which meant he had regular deadlines to meet—and he met them. Do I look like Charles Dickens to you?

Well, even if you answer yes, I won’t be trying to emulate him. Rather, I plan to stick with my usual method of writing a book, which involves alternating between writing, research, and daydreaming in a way that seems to defy all principles of order and reason. And—here’s the challenging part of this experiment, and the part I find slightly scary—I’m going to make big chunks of that creative process visible in the newsletter. I’m also going to encourage readers who feel so inclined to participate in the process—to react to book-related things that appear in the newsletter with acute questions or biting criticism or (if you must) adulatory affirmation.

Some obvious questions:

1) Does this mean the end of the Earthling, NZN’s distinctive Friday assemblage of news and comment that is geared specifically to inhabitants of this planet? No!

2) Does it mean fewer of the longish, polished (by Substack standards, I mean) essays that I typically publish on Monday or Tuesday? Yes! They won’t disappear entirely, but their frequency will have to decrease if I’m going to pull this thing off.

3) What will fill the place of the missing essays? While I can’t answer that question with breathtaking precision—this is, after all, an experiment—I can say a bit about elements we’ll experiment with as we figure out what works and what doesn’t:

There will be reflections by me—maybe written, maybe spoken, maybe both—on issues I’m grappling with in writing the book. These could be issues about substance (cognitive empathy is a subtle and complex thing, and my own exploration of it is ongoing), or issues about how best to present this subject to readers, or maybe generic book-writing issues—problems I’d encounter regardless of what the book was about.

There will be new kinds of interactions with readers. For example, I want to try some Zoom calls with paid subscribers in which I field their questions or comments. (These could even get self-helpy if people have questions about cognitive empathy challenges in their daily lives.) And I plan to sometimes respond to questions left in the newsletter’s comment section via podcast monologues that may also appear in written form.

There will be new kinds of guests on Nonzero podcasts, and new genres of podcast content, and new ways of integrating material derived from podcasts into the newsletter. There will certainly be more podcasts with explicit connection to cognitive empathy (though the subjects of such podcasts will range far and wide, from international affairs to marital relations to mindfulness meditation).

Even though I’m not Charles Dickens, there will be excerpts of the work in progress—but they’ll appear irregularly and in various states, ranging from highly refined to highly in need of refinement. The latter kind may be accompanied by pleas for help.

There will be things that I don’t now envision but that will surface in the course of the trial and error that will drive the evolution of this endeavor.

So that’s the plan—to build the airplane as we fly it. I hope you’ll come along for the ride and, if you feel like it, help with the navigation. (And remember: This airplane thing is just a metaphor. You won’t actually die if the experiment fails.) Feel free to start providing navigational aid by leaving comments below. Takeoff is this Monday.

Images: Charles Dickens writing; Charles Dickens not writing.

I think you are cleverly capitalizing on the very human inclination to want to help on Other People's Projects. Tom Sawyer painting Aunt Polly's fence and rousing his friends to *want* to help is my favorite literary example and you channeled Sawyer's spirit nicely in your announcement. This WILL be fun!

I recommend making use of David McRaney's piece (https://youarenotsosmart.com/2011/08/21/the-illusion-of-asymmetric-insight/)

an excerpt: "In a political debate you feel like the other side just doesn’t get your point of view, and if they could only see things with your clarity, they would understand and fall naturally in line with what you believe. They must not understand, because if they did they wouldn’t think the things they think. By contrast, you believe you totally get their point of view and you reject it. You see it in all its detail and understand it for what it is – stupid. You don’t need to hear them elaborate. So, each side believes they understand the other side better than the other side understands both their opponents and themselves."