Blinken’s China damage control

Plus: Wizard of the Kremlin, AI updates, Cold War II silver lining, outer space catastrophe, paid subscriber perks, and more!

Secretary of State Antony Blinken heads to Beijing this weekend in hopes of initiating what President Biden has said will be a “thaw” in relations between the US and China. Blinken’s work is cut out for him. One of the few things the two countries have successfully collaborated on during the past decade is the deterioration of their relationship.

It’s hard to say which country has made the bigger contribution to his project, but over the last two years, at least, Washington seems to have taken the lead. The Biden administration has orchestrated sweeping restrictions on China’s access to advanced microchips and chipmaking equipment—a move that, whatever its merits, is naturally taken by China as a declaration of economic war. (Some have called it the digital-age equivalent of the US-led embargo on oil and other critical resources that led Japan to attack Pearl Harbor.) Biden is also engineering a big expansion of America’s Pacific military presence, which China, rightly or wrongly, finds threatening. And on the issue of Taiwan, Biden has abandoned the four-decade-old policy of “strategic ambiguity” for more pugnacious talk.

Meanwhile, in Congress, legislators compete for the title of most histrionically Chinaphobic. Rep. Mike Gallagher, chair of the House special committee on China, says we’re in an “existential struggle” with China and “time is not on our side.”

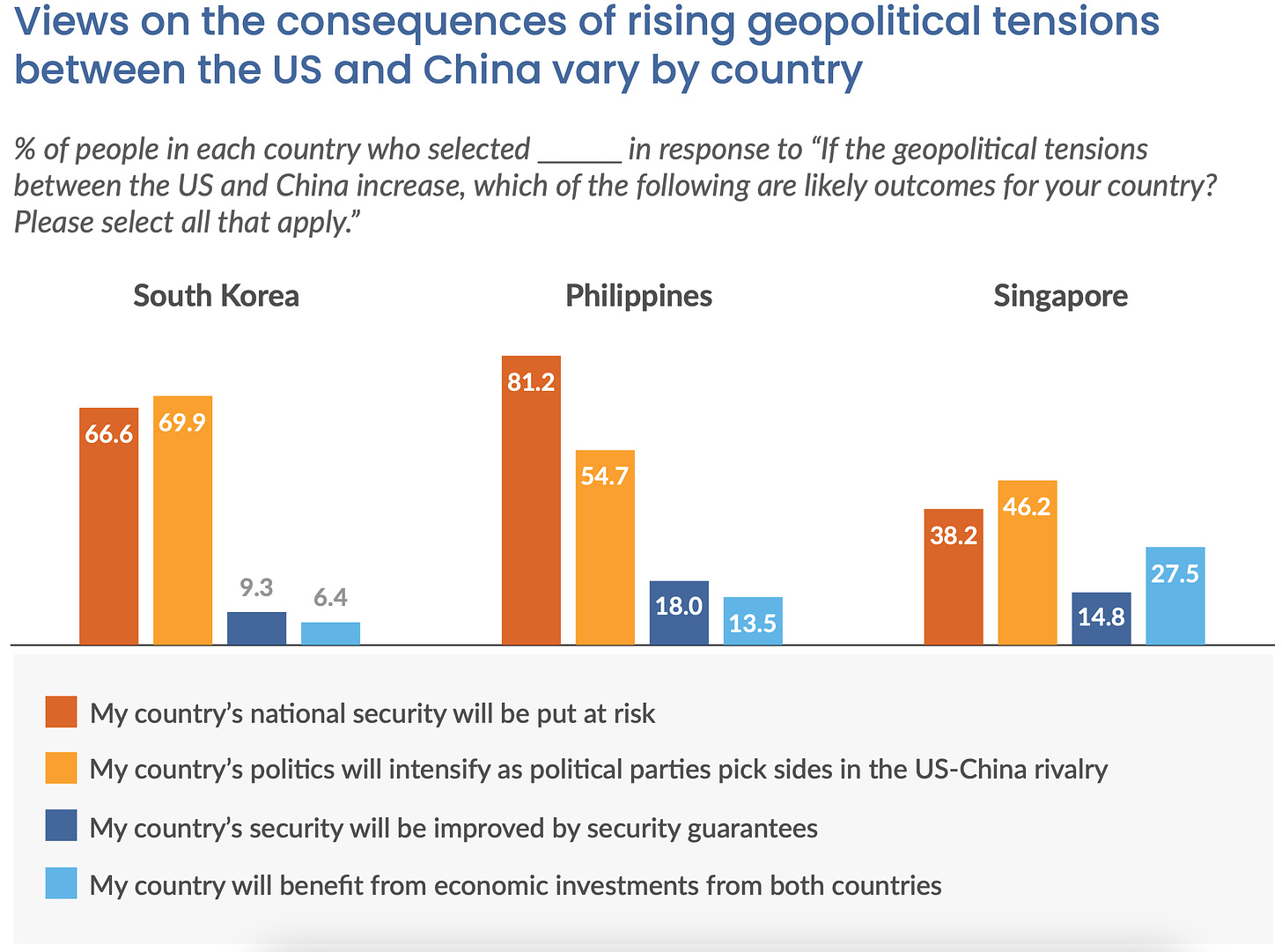

If you ask America’s China hawks to justify their support for policies and rhetoric that amp up trans-Pacific tensions, many will say that, for one thing, we have to protect our friends in the region from China’s bullying—not just Taiwan, but countries like South Korea and the Philippines. But it turns out that if you ask people in South Korea and the Philippines how they feel about rising tensions between the US and China, they’re not enthusiastic. According to a new survey commissioned by the Eurasia Group and assessed in Responsible Statecraft by Jim Lobe, people in those countries have two big concerns: Rising tensions, they fear, will both damage their national security and intensify political combat within their countries between pro-US and pro-China factions.

In the US there would seem to be less factionalism on the question of China. On average, more than 20 bills that reference China are introduced in Congress each week, and very few of these references are positive. Spouting anti-China rhetoric is one of the few bi-partisan pastimes on Capitol Hill. Where is political polarization when you need it?

This week Rep. Lauren Underwood, during a panel discussion on US-China relations, suggested that there’s less congressional consensus than meets the eye. She said many anti-China bills are intended to pave the way for labeling any legislator who opposes them as “soft on China” when campaign season rolls around. As a result, “a lot of colleagues are trying to neutralize a CCP or Chinese attack in the electoral context by wrapping themselves in the blanket of bipartisanship.”

Unfortunately, this surrender to China hawks leads to legislation and rhetoric that inflame international tensions—and, ultimately, it seems, inflame domestic political tensions in places like South Korea and the Philippines. When America sneezes, as the saying goes, the world catches a cold.

More than two years ago, in the early months of the Biden administration, Blinken met with Chinese officials in Alaska and treated them to a public sermon about the moral superiority of America to China (to which they responded in kind). Publicly showering disrespect on a great power isn’t generally considered best diplomatic practices unless your goal is to make relations with it worse than they are. Which is what happened.

These sermons are also ineffective on their own terms. Lecturing countries about human rights—especially big, powerful countries—rarely helps and sometimes makes things worse, creating more human suffering in the end. And one thing that’s guaranteed to create more human suffering is if the world’s two economic superpowers don’t cooperate to address the many unaddressed and under-addressed international policy challenges. (Two of these—AI policy and space policy—are mentioned in this issue of The Earthling, below. There are many, many others.)

In defense of Blinken: When he met with Chinese officials in Alaska, he was new to the job. Maybe this weekend we’ll find out what he’s learned since then.

Attention paid subscribers!

This week we bring you the latest editions of:

Earthling Unplugged, Bob’s conversation with NZN staffer Andrew Day about this week’s Earthling items.

The Parrot Room, the after-hours, weekly conversation between Bob and Mickey Kaus. You can find the new episode tonight in your paid-subscriber podcast feed (to set that up, just click the link above, click the “Listen on” button on the audio player, and follow the instructions).

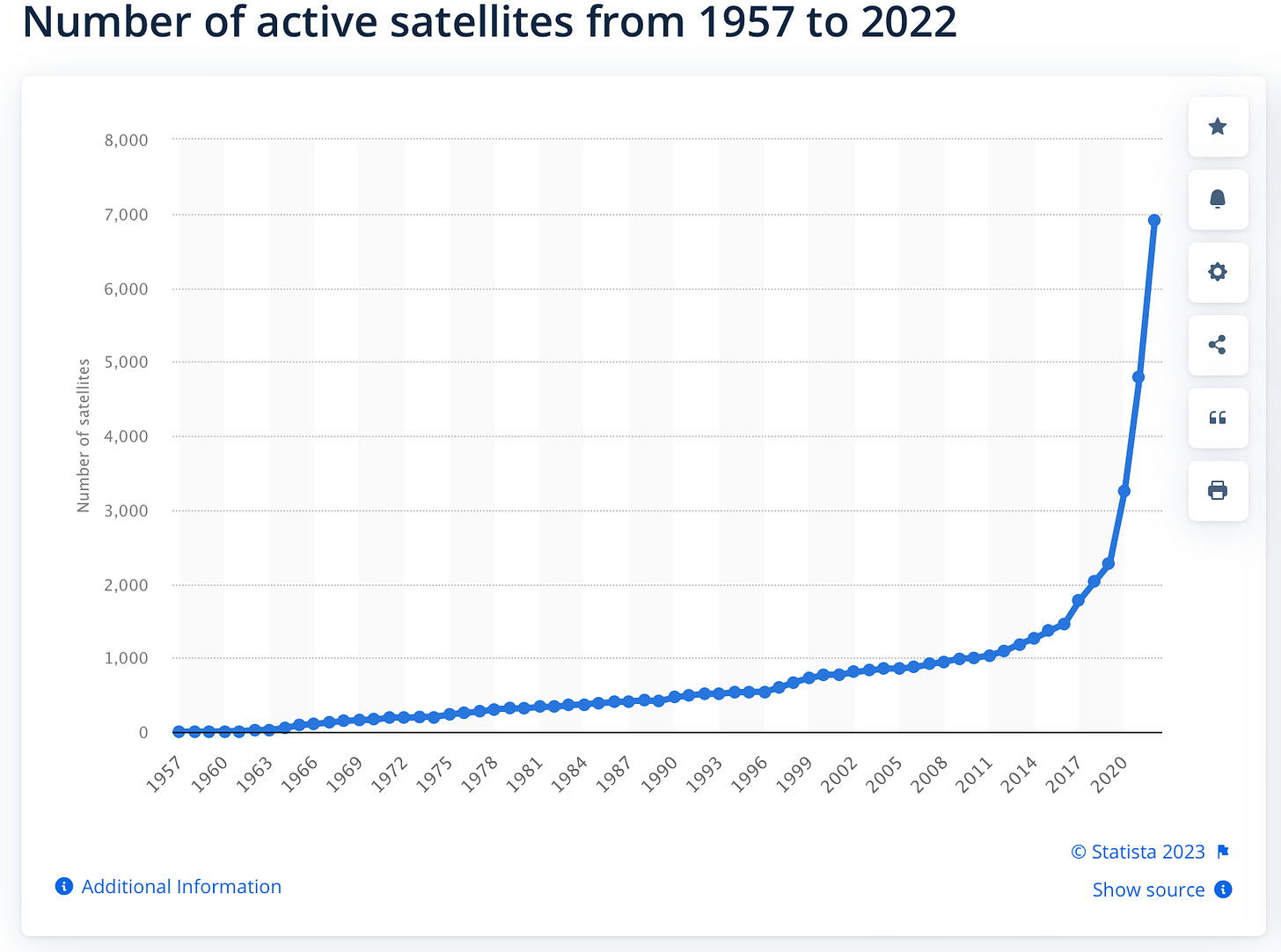

A new report by the RAND Corporation says we’ll need global governance to solve the traffic problem in outer space—and we’ll need it soon. The number of objects in space more than tripled between 2019 and 2022, and there are now around 8,000 active satellites up there. Among other congestion hazards, an accident in space could set off a cascade of collisions, mediated by proliferating debris, that disrupt satellite-provided services. Yet managing space traffic is an “informal, ad hoc, and often ill-coordinated process,” the authors write.

The report explores the possibility of creating an international space traffic management organization (ISTMO). Some experts doubt that such an agency is feasible—understandably, in light of the dismal state of international cooperation. To help ensure that an ISTMO can succeed, the RAND researchers make several recommendations, such as convening the US, China, and other space powers to discuss establishing it.

Serious question: What would be the harm of Secretary of State Blinken proposing such a thing, now that he’s trying to demonstrate America’s desire to mend relations with China? Wouldn’t this lead to, at worst, good publicity for the US? And, at best, reduced chances of a celestial catastrophe?

Four AI updates:

Here is a headline from CNBC: “It’s ‘kind of scary’: Paul McCartney used A.I. to reunite with John Lennon on new Beatles record.” But there’s less here than meets the eye. The AI didn’t do some kind of deep fake of Lennon’s voice and render him singing a song written after his death. Rather, it took a low-quality recording of him doing a song the Beatles had never recorded under studio conditions and then isolated and enhanced his voice, thus permitting a presentable version of the song to be released after some remixing. So this wasn’t as “scary,” as, say, the AI-composed and then deep-faked song “by” Drake and the Weeknd that caused a stir two months ago. Unless, maybe, you’re an audio engineer who makes a living by cleaning up sub-par recordings.

This week we pay OpenAI CEO Sam Altman the highest of compliments: He’s not far behind us! Only days after NZN argued for US-China rapprochement as a critical path to global cooperation in addressing risks posed by AI (in an NZN piece that was also published in the Washington Post), Altman called for US-China cooperation to guard against AI risks. In the event that Altman would like to shorten the lag between our pronouncements and his, our consulting services are available at the usual rate.