Earthling: Biden's pan-American party faces RSVP problems

Plus: Avoiding Cold War II; Musk vs. China; Iran closer to bomb; etc.

NZN is back! After a month devoted to spiritual reflection, intellectual growth, and watching the NBA playoffs, the hard-working Nonzero team is again in harness. But don’t think this is a return to normalcy! There are a couple of changes:

1) The every-Friday Earthling edition (i.e., what you’re reading) is now officially a “section” of the newsletter, which means that if you go to the newsletter’s home page you can click “The Earthling” and see all the Earthlings.

2) The edition of the newsletter known as the “usually-on-Monday-but-sometimes-on-Tuesday-and-(when-Bob’s-writer’s-block-is-especially-bad)-occasionally-on Wednesday edition” will change in character. Sometimes it will be what it’s almost always been—a longish (2,000-2,500 word) essay. But often it will be something… something else. I’m not sure what; I’m just sure I’m going to do more experimenting with different formats.

Anyway, as the newsletter continues to evolve, please feel free to give me feedback in the comments section so I’ll have a sense for how the various variants are being received.

–Bob

PS If you’re not already all-too-familiar with my views on the Ukraine war, you can listen to me discuss them on the episode of Andrew Sullivan’s Dishcast that is scheduled to drop today.

The Biden administration seems to be preparing for next week’s Summit of the Americas, a gathering of western hemisphere leaders to be held in Los Angeles, by annoying much of the Americas. In keeping with the central theme of Biden’s foreign policy—that the US is leading a global struggle against autocracy—the administration has refrained from inviting Cuba, Venezuela, or Nicaragua. And this has antagonized such invitees as Chile, Argentina, and Mexico. Mexico’s president has even threatened to stay home unless the invitation list is expanded.

So this year’s Summit of the Americas—the ninth of the every-few-years meetings, and the first held in the US since the inaugural meeting in 1994—threatens to be “a high-profile flop,” according to CNN.

Meanwhile, in the Middle East, the president has carved out a Saudi-Arabia-sized exception to his global fight against autocracy. Though as a candidate he vowed to ostracize brutal Saudi autocrat Muhammad bin Salman (punishment for bin Salman’s having a troublesome Washington Post columnist chopped up into little bits), Biden has now decided to help rehabilitate MBS by honoring him with a personal visit.

In exchange, apparently, Saudi Arabia will put more oil on the market—which, in a sense, will contribute to the global struggle against autocracy, by making oil sanctions on autocratic Russia more politically palatable. (If bolstering brutal autocrats in the name of a global struggle for freedom sounds hauntingly familiar, you may be having flashbacks from the first cold war.)

As if Elon Musk didn’t have enough enemies! Asia Times reports that “Chinese state researchers are calling for the development of anti-satellite capabilities against… SpaceX’s Starlink satellite internet constellation.” Apparently Musk’s satellites, in addition to providing internet access to consumers, could aid the US military in various kinds of confrontations with China. So, say five co-authors of a paper in the Chinese journal Modern Defense, “a combination of soft and hard kill methods should be adopted to make some Starlink satellites lose their functions and destroy the constellation’s operating system.” That way China can gain “advantages in the fierce space game.” (Kind of makes you wish some visionary US politician would start talking about the importance of a treaty governing anti-satellite weapons…)

Are there lessons learned from the first Cold War that might guide us through the US-Russia proxy conflict unfolding in Ukraine? In the Atlantic, Anatol Lieven of the Quincy Institute lists four: (1) Recognize military weakness; Russia is in no position to dominate Europe, given its struggles in Ukraine. (2) Distinguish between vital and peripheral national interests; whether Russia controls eastern Ukraine is a peripheral interest for America but a vital one for Russia, and Moscow may resort to extreme measures—possibly including the use of nuclear weapons—if that interest is threatened. (3) Recognize the overlap of interests with adversaries; Russia and the US both oppose ISIS, for example. (4) Avoid a new McCarthyism that brands foreign policy dissidents as traitors who “recite Putin talking points.” These lessons from history, Lieven writes, could help us avoid another costly “militarized global crusade.”

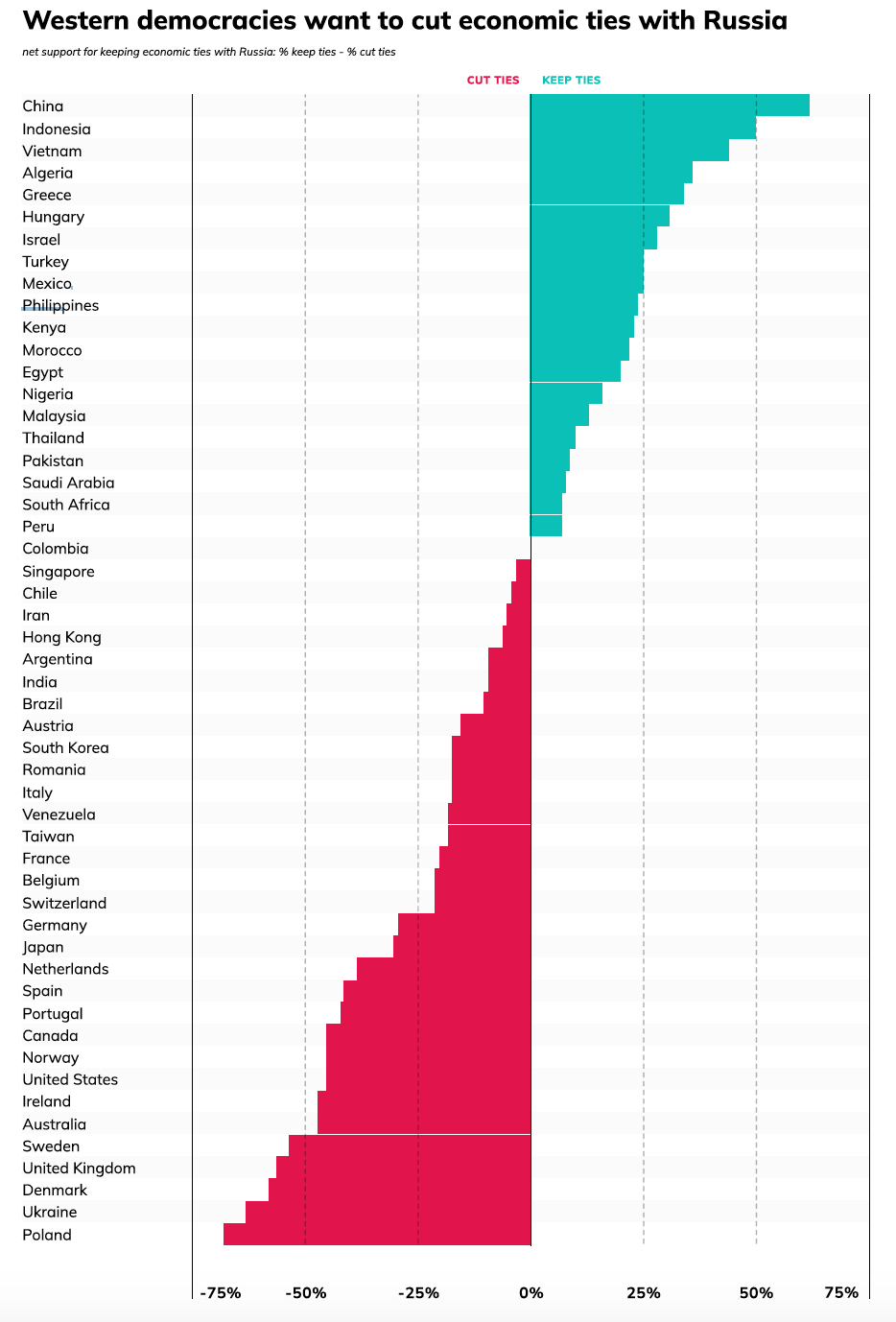

Opinions about Russia–and about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine–differ sharply between the West and the rest, according to a survey of 52 countries conducted for the Alliance of Democracies. In virtually all western liberal democracies, most people expressed negative views of Russia and supported cutting economic ties with Moscow as punishment for the invasion of Ukraine. But a number of populous non-western nations—including China, Pakistan, and Indonesia—expressed net positive views of Russia and support for preserving economic ties.