Earthling: How Mike Pompeo helps China avoid accountability

Plus: Arctic nuclear time bomb, robot dogs of war, Biden vs. peace talks, tweet of the week, and more!

A week ago the United Nations Human Rights Council rejected, by a vote of 19-17, a motion to debate human rights abuses in Xinjiang province, where China has for years subjected large numbers of Muslims to involuntary confinement even though they’ve committed no crimes. Among the people complaining the loudest about this sad outcome are some of the people most responsible for it.

Former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, for example, tweeted that this “disgrace” was “par for the course from the United Nations.” To understand how people like Pompeo made the disgrace more likely, you have to understand something about the United Nations that should be obvious but seems to sometimes elude people: It’s a political body.

Pompeo was once a member of another political body: the US House of Representatives. He may have noticed while there that if you’re going to get other members to support you on a vote you consider important, it helps to be on reasonably good terms with them.

Among the countries that voted with China on the UN Human Rights Council were Venezuela and Cuba. For years—with the full-throated support of Pompeo, including, consequentially, when he was Secretary of State—the US has been waging an economic jihad against both countries, smothering them in sanctions that have inflicted great suffering on their people. This leaves their governments extremely ill-disposed to accommodate the US at the UN—and, more fundamentally, has incentivized them to build bonds with China that incline them to accommodate China.

Are there human rights abuses in Cuba and Venezuela, as alleged by supporters of America’s sanctions regimes? Sure. But one thing Pompeo may have noticed while in Congress is that you have to set priorities and accept tradeoffs; you can’t solve all the world’s problems, and if you try you may wind up solving none of them. And what China has been doing in Xinjiang is way worse than anything going on in Cuba or Venezuela.

Besides:

(1) There are human rights abuses comparable to those in Cuba and Venezuela—or worse—in lots of countries America is on good terms with. The main reason Cuba and Venezuela get singled out for punishment is that there are strong ethnic lobbies—especially influential in Florida, a politically momentous state—that want to see them punished.

(2) Sanctions virtually never work. The US has been sanctioning Cuba for six decades and still can’t declare victory.

Let’s do a radical thought experiment. Suppose that over the past few decades America’s policy toward its western hemisphere neighbors had been less capriciously judgmental, more devoted to building good relations with other governments. In this alternative world, the Cuban and Venezuelan governments are friends of America, and more dependent on good relations with it than on good relations with China. In that world, the 19-17 vote at the UN Human Rights Council might well go in the other direction.

Of course, in that world Mike Pompeo would have fewer opportunities to disparage the UN. But, again, life is full of painful tradeoffs.

This week retired Admiral Mike Mullen suggested that the US should do “everything we possibly can” to resolve the Ukraine war diplomatically. Mullen was once chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff—the nation’s highest-ranking military officer. So you might think the White House would take his concerns to heart.

You might be wrong. The Washington Post reports that US officials have ruled out pushing Ukraine to negotiate with Russia—despite thinking neither side can win the war “outright.” The report comes a week after Ukrainian President Zelensky ruled out talking to Russia so long as Putin is president.

As Mullen pointed out, the war will have to end sometime, probably following negotiations. “The sooner the better as far as I’m concerned,” he added. But with Russia having escalated militarily following Saturday’s bombing of the bridge linking Crimea to Russia, and with peace talks apparently off the table, sooner seems less likely than later.

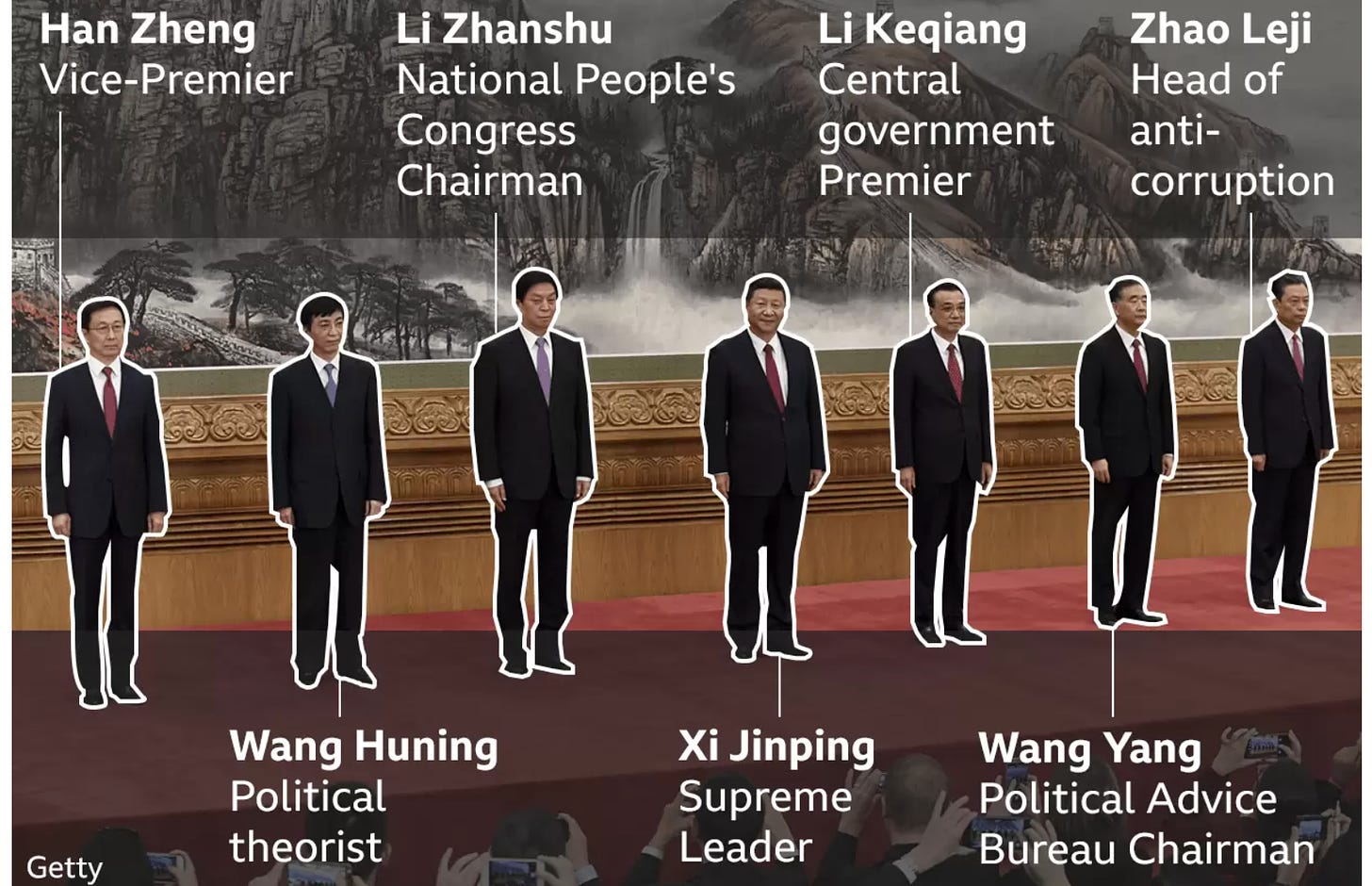

At next week’s Chinese Communist Party Congress, Xi Jinping will almost certainly be handed a third five-year term as China’s leader. This isn’t as immediately precedent-shattering as it’s been depicted in western media. Jiang Zemin served as head of the Communist Party for 13 years, until 2002. And there’s never been a legal limit on the number of terms for that office. China’s president used to be restricted to two terms—and that law has been changed to accommodate Xi—but the presidency is a basically ceremonial office.

All that said, Xi will now be on course to set a leadership longevity record for the post-Mao era by the end of his third term. And this does seem to signify a firm grasp on power. But it’s easy to misunderstand this power, writes China expert Kerry Brown in the New York Times: “There is indeed an autocrat who rules modern China, but it is the party that Mr. Xi serves, not the man. And in a strange way, he is as much a captive of the party as everyone else.”

Some other background material:

1) David Brown of the BBC has a rundown on what to expect from the CCP conclave, which starts Sunday.

2) Political scientist Jessica Chen Weiss recently came on the Nonzero Podcast to discuss how the US should relate to China in the Xi era. That episode won’t air until next week, but we’re giving early access to paid subscribers, who can watch or listen to the conversation here.

Six robotics companies—including famous MIT-spinoff Boston Dynamics, maker of dazzling robot dogs—have pledged not to support the weaponization of their technology, Axios reports.

It’s a nice gesture, but there are two reasons not to expect it to alter the trajectory toward the automation of war: