Earthling: Is Globalization Over?

Plus: Nuclear convoy follies, fake carbon offsets, false flag in Ukraine? …and more!

The Economist magazine, a tireless champion of free trade, warned last week that globalization is giving way to economic nationalism. And President Biden’s “aggressive industrial policy”—big subsidies for domestic manufacturing, made-in-the-USA mandates, bans on tech exports to China, etc.—is accelerating the process, say the magazine’s editors. “An era of zero-sum thinking has begun,” they write.

Not everyone would agree. In the Wall Street Journal, Jon Hilsenrath and Anthony DeBarros argue that globalization isn’t dying—it’s just changing. As US-China tensions grow, risk-averse companies are diversifying their global economic ties, creating supply chains more resistant to disruption by geopolitical and other vicissitudes. The Journal quotes Harvard professor Dani Rodrik saying that “what we are witnessing is not a collapse of globalization. It is more a reshaping of it.”

Maybe so, but reshaping globalization could come at a price—and not just the kind the Journal piece acknowledges, like the transitional costs exacted by the breaking of old supply chains as new ones are born. Some political scientists think that economic interdependence militates against armed conflict by raising the costs of war. So whether or not the world economy pays a big price for US-China decoupling, the world ultimately could.

Of course, the claim that economic interdependence tends to be pacifying is controversial. But one case where such interdependence was intentionally nurtured in the name of peace—the creation in 1951 of the European Coal and Steel Community, which morphed into the European Community, which morphed into the European Union—is encouraging. Suppose that in 1946—after two world wars in three decades pitted France against Germany—a visitor from the future had shown up and explained that by the end of the century France and Germany would have the same currency. The reply would likely have been, “Oh really? Which country will have conquered which?”

An underappreciated virtue of international economic integration is its fostering of transparency. China is more opaque than the US would like, but less opaque than it would be if the past few decades hadn’t featured lots of trans-Pacific investment and commerce, with all the travel and logistical and technical collaboration that involves.

This kind of “organic” transparency is important in an age when suspicions among nations can fuel dangerous arms races of new kinds. Concern about what a rival country is up to on various fronts—artificial intelligence, bioweapons, even the genetically engineered enhancement of humans—can lead to reckless research, unconstrained by legal or normative regulation.

In the long run, it would be nice to address some of these arms races the old-fashioned way—via international agreements, complete with international monitoring. In the meanwhile, the kind of transparency economic integration brings can be stabilizing; the less opaque China is, the harder it will be to whip up American fears that lead to overreaction.

All that said, a modest and selective kind of economic nationalism can make it harder to whip up other kinds of fears. The US subsidies that are leading the world’s most advanced microchip maker—Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company—to build a factory in the US may ease American insecurities about the supply of what is increasingly a vital resource. So too with the assurance that our telecommunications infrastructure isn’t in adversarial hands; however slim the prospect that Huawei’s involvement in America’s 5G system would have led to Chinese snooping or sabotage, this involvement would have been fuel for fearmongers. So maybe President Trump performed a service by preventing that.

Still, the broader declaration of tech war on China—Trump’s banning of Huawei smartphones, Biden’s far-reaching restriction on microchip exports to China—seems harder to justify and more likely to backfire.

This week in Davos the Secretary General of the UN, Antonio Guterres, worried about “what I have called the Great Fracture—the decoupling of the world’s two largest economies. A tectonic rift that would create two different sets of trade rules, two dominant currencies, two internets, and two conflicting strategies on artificial intelligence. This is the last thing we need.”

It’s “essential,” he said, for China and the US “to avoid the decoupling of economies or even… future confrontation.” It’s possible, even likely, that avoiding the first will help avoid the second.

For Ukraine, 2014 was a pivotal year, and here is mainstream media’s standard rendering of why:

Peaceful protests against the policies of a pro-Russian president, Viktor Yanukovych, morphed into revolution—the “Maidan Revolution” or “Revolution of Dignity”—after riot police killed dozens of protesters. Yanukovych then stepped down, and Vladimir Putin responded to the revolution by seizing Crimea and supporting separatists in eastern Ukraine.

In a Nonzero podcast conversation recorded this week, Ivan Katchanovski, a political scientist who grew up in Ukraine, says this narrative is misleading in some places and flat-out wrong in others.

Katchanovski, who has written several papers about the revolution, offers a number of amendments to the narrative, the most controversial of which is that riot police were not, in fact, the perpetrators of what became known as “the Maidan massacre”. He says most of the protesters who died were shot, rather, by snipers from far-right groups that supported the protests (but that most of the protesters didn’t support). He says the leaders of these groups hoped that the Yanukovych regime would be blamed for the killings, creating international pressure on him to step down. Which is what happened.

My far-ranging conversation with Katchanovski will go public mid-next-week, but paid subscribers to NZN can watch or listen now.

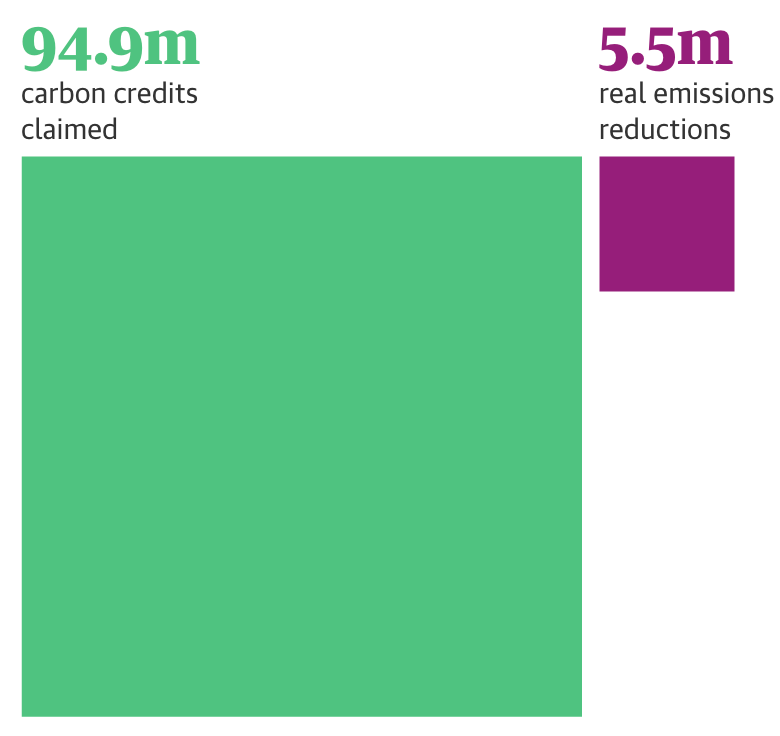

A new study casts doubt on the work of Verra, a nonprofit that is a major certifier of carbon offset credits, which corporations purchase to compensate for their carbon-emitting activities or products. The study found that 90 percent of Verra-certified rainforest carbon offsets, purchased from organizations that conduct forest protection operations, amounted to “phantom credits” because the standards those operations met were so permissive.

About 40 percent of the credits that Verra certifies are from such forest protection operations, and among the companies that buy them are Shell, Disney, and Gucci. Verra overstated how much forest the offsets would save by 400 percent on average, according to the study.

The study was done by the Guardian, the German newspaper Die Zeit, and SourceMaterial, an investigative journalism nonprofit. Verra disputed the findings and said it has helped channel billions of dollars from corporations into rainforest preservation.

NZN’s social media monitoring team is on constant alert for tweets that bridge national, partisan, and ideological divides. This vigilance often goes unrewarded; good Twitter citizens are hard to find. But our Tweet of The Week provides a welcome exception to the norm of point-scoring tribalism: