Earthling: Moscow murder mystery solved

Plus: War-on-Blob update, how Cold War II could tank the economy, Soil-ent Green, paid subscriber perks, and more!

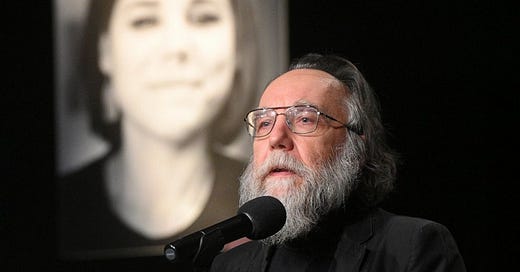

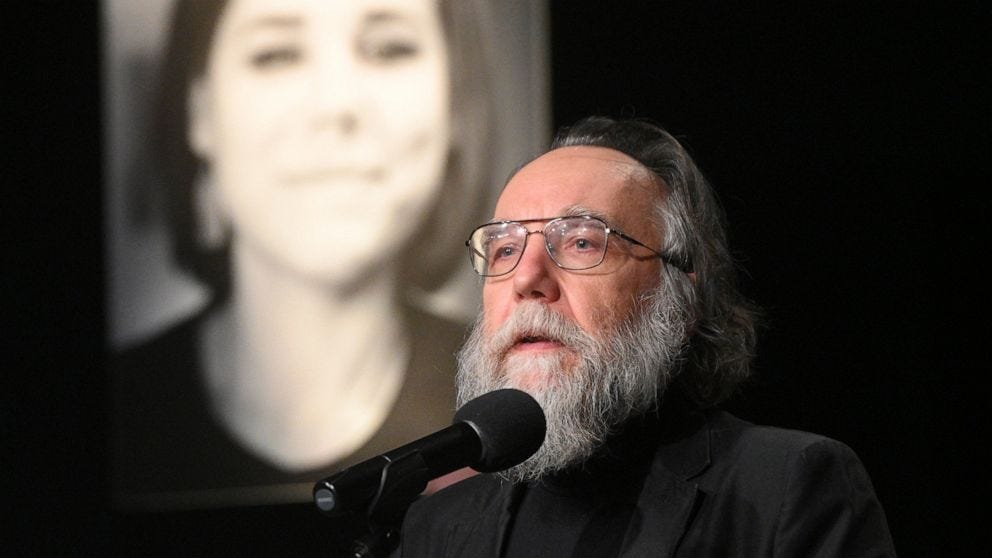

After Daria Dugina, daughter of Russian political philosopher Alexander Dugin, was killed via car-bomb in Moscow this summer, Russia accused Ukraine of sponsoring the murder, and the Ukrainian government denied involvement. Apparently Russia was right.

This week the New York Times reported that, according to unnamed US officials, “parts of the Ukrainian government” authorized the bombing, though whether President Zelensky himself OK’d it remains unclear.

Two questions arise:

1. Why did the Biden administration decide to leak this story? Consensus Twitter speculation is that the administration was sending some sort of message to the Zelensky administration. Like: “Hey, now that everyone’s talking about nuclear war, maybe you should cool it with the inflammatory and potentially escalatory special ops for a while?” The leak may even have been a pre-emptive strike against a specific Ukrainian special op the Biden administration had caught wind of. In any event, officials who leaked the story let it be known that the US had privately rebuked the Ukrainian government for the Dugina killing.

2. Why did the Ukrainian government sponsor this terrorist attack? Presumably the goal was the standard goal of terrorism: to terrify and intimidate. But what kinds of people would the Ukrainians have been trying to intimidate? What was the target audience? It isn’t clear whether the intention was to kill Dugina or her father or both, but for audience-targeting purposes it doesn’t matter, since both of them were vocal pro-war nationalists. So the message to Russian elites would have been: You’ll have a better chance of living another year if you don’t spout off about how Russia should intensify its war effort.

The odd thing about this motivation, though, is that there was obviously a good chance that the killing would contribute to the intensification of Russia’s war effort. That’s the consequence I fretted about in NZN right after the murder: “This could lead to escalation of the Ukraine war, since Russia will blame Ukraine for the murder,” thus “stoking a thirst for revenge and, in particular, inflaming Dugin’s already belligerent fan base.”

Did something like that happen? At least one expert says yes. A couple of weeks ago, before the revelation of Ukrainian complicity in the killing, the scholar Marlene Laruelle (who, as it happens, had appeared on the Nonzero Podcast in April) published a New York Times op-ed about the growing political pressure on Putin—from both anti-war and pro-war forces—as the Russian war effort floundered. Describing pressure from “the party of war,” she wrote:

Through the summer, the level of criticism was manageable for the regime. But things began to change in August, when Darya Dugina, the daughter of one of Russia’s best-known imperial ideologists, Alexander Dugin, was assassinated in Moscow. The perpetrators and purpose of the attack are unknown. But the effect was clear. By bringing the conflict into one of the capital’s fanciest neighborhoods, the murder confirmed the hawks’ dim view of the war effort. Since Ms. Dugina’s death, the party of war has been using her “martyrdom” to renew calls for a full-scale war in overtly eschatological tones.

The military reversal of recent weeks has played into their hands.

To be sure, that military reversal—the large-scale Russian retreat in mid-September—would likely have been enough to intensify the war effort, complete with the kind of mobilization Putin ordered, even if Daria Dugina had still been alive. Still, as Putin calibrates his policies and rhetoric—and makes such decisions as whether to use a nuclear weapon—he is navigating a political landscape whose pro-war faction has been empowered by Dugina’s murder.

In particular: Dugina’s father—who was never as influential in Russia as many in Ukraine and the West believed—now has a bigger platform and megaphone, and he is definitely fired up.

Indeed, his constituency is now powerful enough for Putin to have nodded to it in last week’s famously Manichaean speech about the threat the US-led West poses to Russia: “They see our thought and our philosophy as a direct threat. That is why they target our philosophers for assassination.” (Maybe this insinuation of US involvement in the murder is one reason the Biden administration chose to distance itself from it?)

There’s also this damage to the Ukrainian cause: Intentionally killing civilians is a war crime, and part of Ukraine’s international appeal rests on the perception that Russia commits war crimes but Ukraine doesn’t.

A word that is increasingly deployed as an argument stopper—in many realms, not just geopolitics—is “agency.” If you suggest that it was a mistake for George W. Bush (in defiance of warnings from European leaders and his own ambassador to Russia) to invite Ukraine to join NATO, you are denying Ukraine its “agency.” If you suggest that the US, which is giving massive and critical military support to Ukraine, should also encourage peace talks, or go even further and push for a particular kind of peace deal, you’re denying Ukraine its “agency.”

Whatever the Biden administration’s reason for publicizing Ukraine’s role in the very unwise murder of Daria Dugina, one effect may be the welcome one of suggesting that there’s such a thing as too much deference to Ukraine’s agency.

Paid newsletter subscribers can listen to former NZN employee Nikita Petrov describe his recent nerve-racking departure from Russia (complete with “special questioning” at the airport by an agent of the FSB, successor to the KGB) and discuss the way the war is being perceived in Russia. The podcast will go public next week. (See the very bottom of this post for the link.)

But wait–there’s more! Paid subscribers can also listen to an audio version of “Biden’s grand and dangerous vision.” The original essay was published on September 20.

Writing for the Verge, Eleanor Cummins takes a look at people who want to have their corpses composted after they die, and at the companies that accommodate them. The basic idea was captured in an architecture student’s 2013 graduate thesis. “Our bodies have nutrients,” Katrina Spade observed. “What if we could grow new life after we’ve died?” This may sound like an old idea—buried bodies have been known to decompose, after all—but it’s controversial. The Catholic Church opposes human composting, and only a few American states have legalized it. Graphics from the Verge illustrate the steps involved, including step 5, shown below.

The world economy could be the next casualty of international tensions. And, according to an analysis by economic historian Adam Tooze in the New York Times, that’s not just because the most salient of those tensions—the Russia-Ukraine war—has raised the price of food and fuel, exacerbating post-pandemic inflation. It’s also because broader tensions, notably between the West and China, impede the kind of international cooperation needed to address global inflation without sending the world into a tailspin.

Tooze says we’re stuck in a vicious circle of competitive interest rate hikes. When, for example, the US raises rates to cool its economy and curb inflation, its currency gets stronger, which means other countries will face new inflationary pressure unless they strengthen their own currencies by raising interest rates. This reaction to US policy dilutes its effect, thus encouraging further US rate-raising, and… and so on. Such a bidding war can wind up sending interest rates higher than anyone was hoping for and sending the world into deep recession.

What we need then, is mutual restraint in the form of coordination among the world’s big central banks. Good luck with that, Tooze writes: