Earthling: Russian Foreign Minister schools US leaders in political theory

Plus: Chess robot attacks child; more Manchin whiplash; Is Biden Trump 2.0?; etc.

If you’ve studied international relations (IR), you’re probably familiar with the “security dilemma”:

One state builds up its forces to increase its security. But other states, seeing this build-up from afar, feel less secure—and build up their own forces in response. Rinse and repeat. Let the process continue long enough and you’ll have a bunch of increasingly well-armed countries in a state of tension—perhaps escalating tension—even though all think of their contributions to this spiral as purely defensive.

You might think foreign policy makers—schooled, as they tend to be, in international relations—would keep the security dilemma in mind as they do their strategic planning. But according to Stephen Walt, a leading IR scholar, you’d be wrong. Writing in Foreign Policy, Walt says he’s “struck by how often the people charged with handling foreign and national security policy seem unaware of it—not just in the United States, but in lots of other countries too.”

Western leaders may really believe that NATO is, as they often say, a “defensive alliance” and that its expansion reflects no desire to attack Russia. Even so, Walt argues, they should understand that Russia will probably see things differently. That is the lesson of the security dilemma.

The dilemma may be even more loaded with explosive potential than the standard rendering of it suggests. As IR scholars such as the late Robert Jervis have emphasized, the problem isn’t just that an adversary may mistakenly infer aggressive intent from a military build-up. The adversary may in some cases consider the build-up defensive yet still worry that a future leader who inherits the built-up forces will put them to offensive use.

In fact, we have evidence that US adversaries think in exactly this way. Back in 2008, when current CIA Director William Burns was ambassador to Russia, he wrote a memo about Russia’s attitude toward NATO expansion that he pungently titled “Nyet means nyet.” Paraphrasing the stated views of Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, he wrote: “While Russia might believe statements from the West that NATO was not directed against Russia, when one looked at recent military activities in NATO countries (establishment of US forward operating locations, etc.) they had to be evaluated not by stated intentions but by potential.”

Notwithstanding this memo (and notwithstanding an email Burns sent to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice emphasizing that Russian national security elites broadly, not just Putin, considered Ukraine membership in NATO a “red line”) George W. Bush two months later strong armed reluctant European partners into signing a declaration that Ukraine “will become” a NATO member.

We can’t know for sure how things would have turned out if Bush had followed Burns’s guidance. But, arguably, the recent history of US-Russia relations is more comprehensible, and US foreign policy more questionable, if viewed through the prism of the security dilemma.

At the Moscow Open chess tournament, a robot violated an important, albeit unstated, rule of the centuries-old game: do not break your opponent’s fingers. After the AI captured a piece, its seven-year-old opponent made his next move more quickly than is, apparently, advisable—leading the robot to pinch the boy’s finger until onlookers could free him. “The robot broke the child’s finger,” said the president of the Moscow Chess Federation. “This is of course bad.”

On foreign policy, is President Biden just Trump 2.0? New York Times reporter Edward Wong suggests that the answer may be yes.

Both presidents, Wong notes, have assisted Saudi Arabia’s brutal war in Yemen. And Biden has maintained Trump-imposed tariffs on China, along with a hawkish China policy more generally. True, Biden supports the revival of the Iran nuclear deal, which Trump exited in 2018—but that effort has been hampered by, among other Biden positions, a refusal to reverse Trump’s designation of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards as a terrorist group.

Biden’s foreign policy may be even more similar to Trump’s than Wong reports. Rather than remove the substantial sanctions Trump imposed in Latin America, this administration has offered only minor sanctions relief to Venezuela and Cuba.

And Latin America isn’t the only place Biden has mirrored Trump’s seeming indifference to humanitarian concerns. In Afghanistan, Biden has, on top of painful sanctions, added an America First twist that Trump might admire: his administration, having frozen Afghan government assets, is giving some of that money—which remember, belongs to Afghanistan – to relatives of 9/11 victims.

Professor DESTROYS Daily Wire conservative with FACTS.

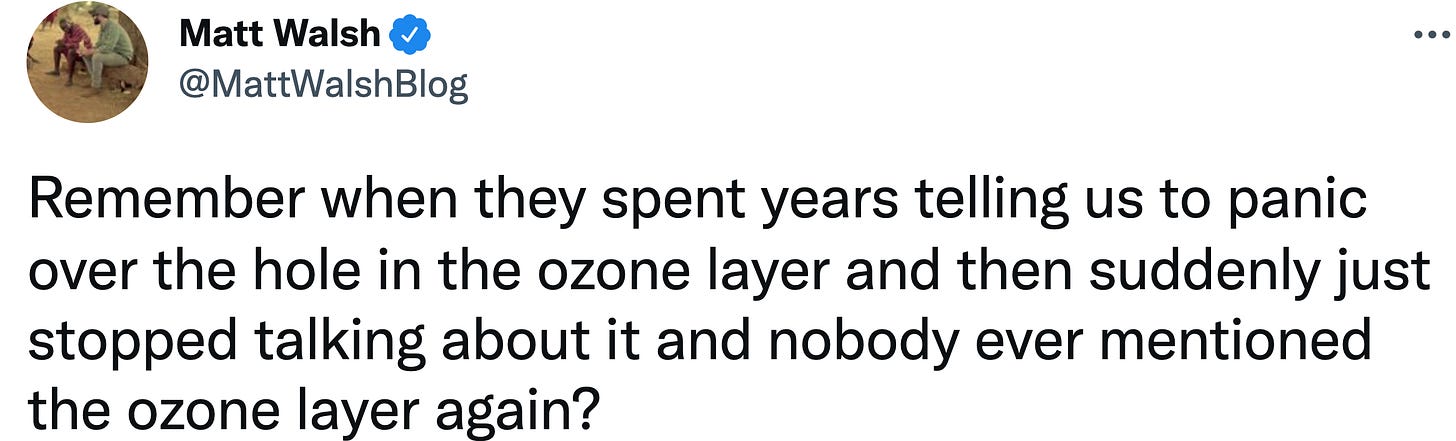

Last week, Matt Walsh of the Daily Wire asked his one-million Twitter followers this rhetorical question:

Walsh didn’t elaborate on who, exactly, “they” were, but we’re guessing he meant the types of people who make a big deal of climate change and may call for strengthened global governance to address it. Well, lucky for Walsh, those same people were on hand to inform him that ozone depletion was a problem until the Montreal Protocol, a milestone in the evolution of global governance, solved it.

On Twitter, political scientist Paul Poast provided useful background information, detailing how the agreement came about and how it works. By the 1980s, the science was clear that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs)—once found in products like hairspray—were depleting the ozone layer, which protects Earthlings from the sun’s radiation. In 1987, the US helped forge an agreement with other wealthy countries to phase out the production and use of CFCs, thereby saving the ozone.

Poast’s summary is useful, but his conclusion that “the Montreal Protocol is NOT a good model for addressing global warming” is too simple. The basic model is sound: