Earthling: Stopping a vicious global warming cycle

Plus: Government by Google?; Ukraine war engulfs Sri Lanka; pollen apocalypse; etc.

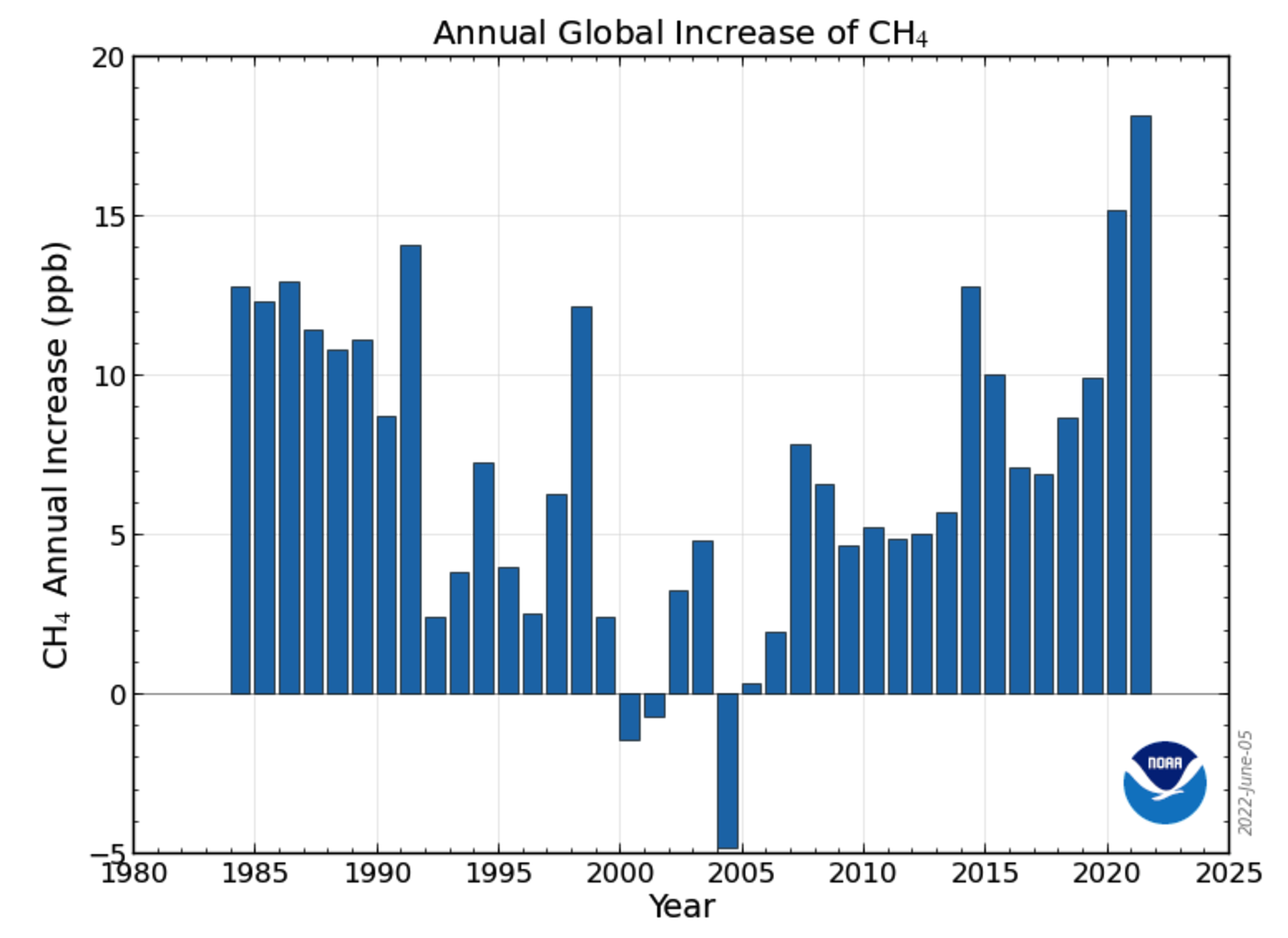

A given amount of methane heats up Earth’s atmosphere much more than the same amount of its more famous fellow greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide—like, 90 times more in the course of a decade. So it’s with some alarm that scientists in recent years have noted not just growth in the amount of methane in the atmosphere but accelerating growth.

They may now have an explanation for the acceleration. A new study, covered in the Guardian this week, finds that global warming increases the amount of methane much more than previously believed. Among the likely reasons: heat spurs methane-producing microbial activity in swamps and other milieus; and rising levels of carbon monoxide—mostly caused by an increase in heat-induced wildfires—soak up natural “detergent” chemicals that would otherwise be free to cleanse the atmosphere of methane.

All told, the growth of methane seems to be about four times as sensitive to warming as scientists had thought. In other words, the vicious cycle—methane produces heating that produces methane—is very, very vicious.

But wait, help may be on the way! Also this week, Business Insider featured an update on the development of satellite-based monitoring that could bring cheaper and more accurate detection of methane leaks.

These leaks (which come mainly from wetlands, oil and gas sites, and landfills) are now commonly detected by aircraft, after which they can be fixed. California’s non-profit Carbon Mapper project, for example, claims to have prevented more than one million metric tons of methane from entering the atmosphere between 2017 and 2021 (the rough equivalent of removing 260,000 gas-powered cars from the road for a year).

Methane-spotting satellites, their boosters say, will yield more cost-effective results. A Canadian emissions-monitoring company called GHGSat has six such satellites in orbit with four more planned by the end of 2023. MethaneSAT, a satellite sponsored by the Environmental Defense Fund, an American NGO, is expected to launch next year.

The rippling effects of the war in Ukraine have sent one island country into economic collapse. Sri Lanka is experiencing severe shortages of food, fuel, and other essentials.

With food prices rising at an annual rate of 60 percent, a survey found that two thirds of Sri Lankan households are cutting back on consumption. The government is hoping for an International Monetary Fund bailout and in the meantime is taking such measures as giving government workers time off to grow crops at home. Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe has warned that as the Ukraine war continues, his nation won’t be the only one brought to its knees.

As President Biden prepares to visit Saudi Arabia next week, his reported aspiration to form a NATO-like alliance against Iran has gotten brutal pushback from an eminent veteran of the national security establishment. In Responsible Statecraft, Paul Pillar—who from 2000 to 2005 was the national intelligence officer for the Near East and South Asia and hence in charge of analysis of those regions for the CIA and all other American intelligence agencies—gives two big reasons the envisioned US-Arab-Israeli alliance would be misguided.

First, Iran doesn’t pose a serious military threat. (Most of its air force equipment, Pillar writes, “belongs more in a museum than on the flight line.”) Moreover, Iran doesn’t have a history of attacking other nations—whereas members of the envisioned NATO-like alliance do. In recent years, writes Pillar, “the biggest instance of interstate aggression in the Middle East is the Saudi air war against Yemen” and the next biggest is “the Israeli air war against Syria, and against Iranian targets in Syria.”

Second, America’s partners in this alliance don’t, on balance, evince commitment to the values America champions any more than Iran does. Neither Israel nor Saudi Arabia “comes close to being a model democracy.”

Though democratic principles apply within Israel proper, they don’t extend to “the 5.3 million Palestinian residents of territories that Israel rules and treats for whatever purposes it wants as an integral part of Israel. Those residents have no political rights.” And as for Saudi Arabia: “Iran at least has had, unlike Saudi Arabia, elections to the presidency and the legislature that have actually mattered.”

Pillar also argues that Israel and Saudi Arabia have been, like Iran, “at least as much a part of the problem of terrorism as of solutions to combat it.”

And finally: Pillar worries that this new alliance “would risk dragging the United States into conflicts that stem from the ambitions and objectives of regional players and not from US national interests.”