Earthling: The War Crimes Question

Plus: China's Ukraine dilemma; war on plastics update; Madeleine Albright appraised; etc.

Is the Pentagon waging information war against the State Department? That’s one interpretation of the fact that this week, as Secretary of State Antony Blinken was asserting that Russians have committed war crimes in Ukraine, anonymous Pentagon sources were emphasizing how few of the bombs, missiles, and artillery shells delivered by Russia have hit civilians.

A Newsweek piece by veteran national security journalist William Arkin quotes an anonymous senior analyst at the Pentagon’s Defense Intelligence Agency saying:

The heart of Kyiv has barely been touched. And almost all of the long-range strikes have been aimed at military targets… I know it's hard to swallow that the carnage and destruction could be much worse than it is. But that's what the facts show. This suggests to me, at least, that Putin is not intentionally attacking civilians, that perhaps he is mindful that he needs to limit damage in order to leave an out for negotiations.

The idea that this quote is Pentagon pushback against the State Department—advanced by Joe Lauria in Consortium News—is plausible. The US military isn’t eager for direct involvement in the Ukraine war (via, say, a no-fly zone), and advocates of direct involvement often invoke reports of Russian atrocities in their appeals. But, Lauria’s theory aside, it’s also true that establishing the intentional targeting of civilians—a pre-requisite for a war crimes conviction—is inherently hard.

That’s partly because accidents happen, but it’s also because a military defending a city inevitably positions some of its assets near civilian buildings. A smartphone photo apparently taken before this week’s Russian strike on a Kyiv shopping mall showed military vehicles parked there. (A Ukrainian who had posted the photo on the internet was reportedly arrested.) Russia supporters claimed evidence that artillery shells were stored at the mall, and an Australian journalist said uniformed soldiers were among the eight people killed.

Block by block fighting, as is happening in Mariupol, is particularly perilous for civilians. Bill Roggio, a military expert at the hawkish Foundation for Defense of Democracies, tweeted this week, “Once you understand how an urban defense is established and maintained, you will see why attackers often will make little distinction between military and civilian targets. This is because the defenders are using every building, street, alley, etc. as a fighting position." (His next tweet emphasized that “this isn't a defense of the Russians. I am merely trying to explain how the battlefield becomes extraordinarily chaotic and dangerous for civilians once the decision is made to wage an urban defense.”)

This week the New York Times provided seemingly strong evidence of one war crime—an order conveyed by radio from one Russian soldier to another (and presumably emanating from a local commander) to “cover the residential area with artillery fire.” But this kind of evidence is rare, so war-crime allegations often rely on patterns of destruction that are hard to explain as collateral damage. Attacks on life-sustaining infrastructure in Mariupol—power, water, etc.—may have been systematic enough to qualify as such evidence; Blinken cited the destruction of “critical infrastructure” in his statement (which didn’t purport to be a legal indictment).

Some have worried that calling Putin a war criminal—which Biden casually did two weeks ago—could impede a peace deal. Blinken, in any event, avoided that issue, saying only that “members of Russia’s forces have committed war crimes”—something that shouldn’t be hard to establish in at least some cases.

For now, with information coming overwhelmingly from the Ukrainian side, and being filtered through a largely (and understandably) pro-Ukrainian western media, a lot of these questions remain shrouded in the fog of war. But we don’t need to await the lifting of the fog to identify one crime Putin definitely committed: invading Ukraine, a clear-cut violation of the UN Charter.

But, however ironically, illegal invasion is one crime that tends not to be the subject of post-war adjudication—maybe because so many powerful people, including recent US presidents, have committed it.

Too bad. If we could put an end to that crime, the frequency of other war crimes would drop considerably.

This week brought bad news and good news in the war on plastic. The bad: For the first time, microplastics have been found in human blood—in 17 of 22 people tested in a Dutch study. The good: Scientists have found that a bacterial enzyme called TPADO can break down (with “amazing efficiency,” one of them said) the plastic used in disposable beverage bottles—the same kind of plastic that was found in most of the blood samples that tested positive. (For earlier instances of this bad-news good-news dialectic, see Earthling accounts of the ecological dangers of plastic proliferation and the steps humans are taking to reduce plastic pollution.)

Daniel Larison, publisher of the Eunomia newsletter, offers a critical assessment of former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, who died this week, in Responsible Statecraft.

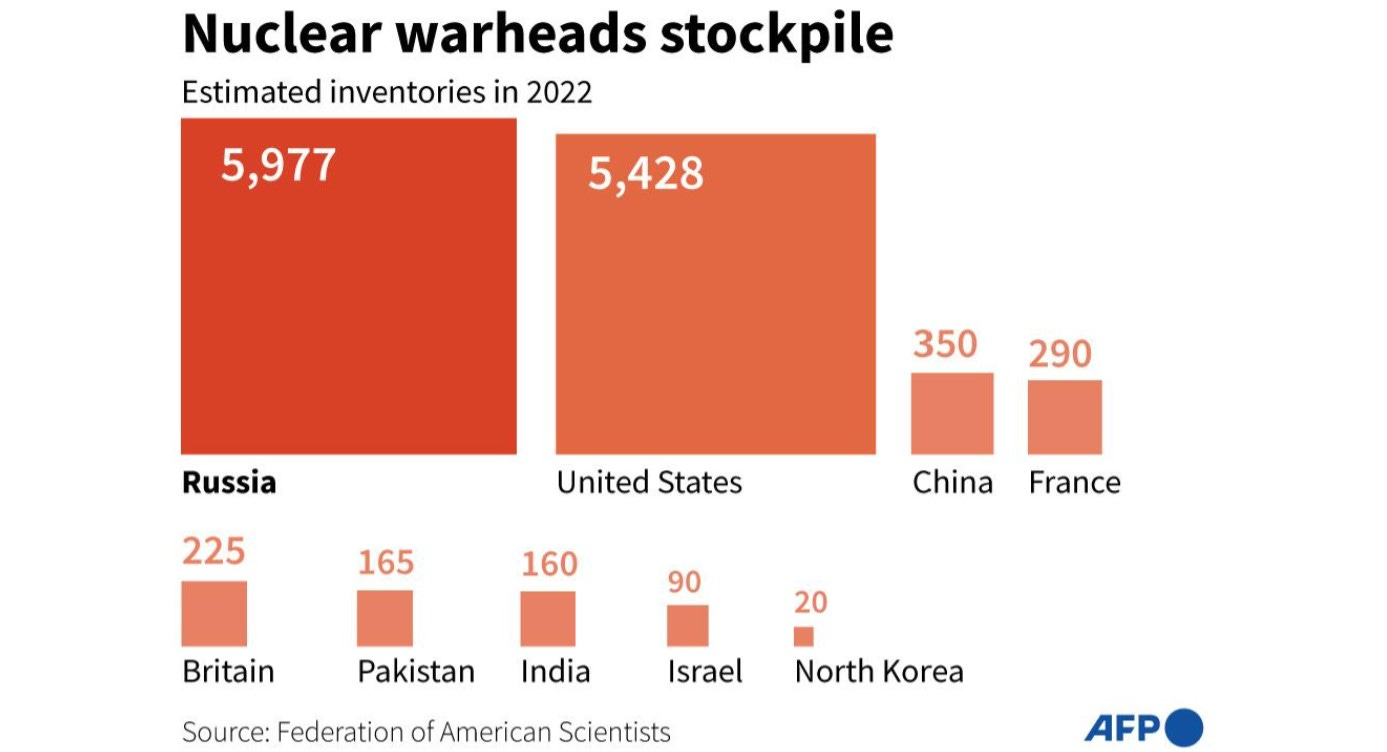

Russia’s war on Ukraine has raised the specter of nuclear war. Unfortunately, many analysts have responded to that prospect in a way that makes it more likely, argues Joseph Cirincione in Responsible Statecraft. Cirincione worries that foreign policy experts are normalizing the idea of nuclear war with their “cavalier armchair strategies.” Part of the problem, he says, is that people don’t grasp the explosive power of even the least powerful nukes. America’s W76-2 warhead—developed so that America would have a “low-yield” nuclear weapon in its submarine arsenal—packs as much punch as 10,000 of the 1,000-pound conventional bombs carried on a B-52.