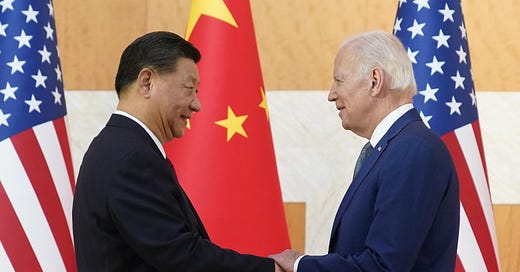

Earthling: Trading places with Xi Jinping

Plus: US special-ops deepfakes, why Crimea matters, AI-wielding conmen, paid subscriber perks, and more!

This week Chinese leader Xi Jinping got a lot of attention by saying “Western countries—led by the US—have implemented all-round containment, encirclement and suppression against us, bringing unprecedentedly severe challenges to our country’s development.”

The Wall Street Journal called this “an unusually blunt rebuke of US policy” and the Washington Post called it “an unusually explicit public riposte of the United States by the Chinese leader.” And various commentators called it evidence of deep and irrational hostility. Fox News’s Laura Ingraham said that Xi “hates this country.” And social media pundit Noah Smith tweeted, “What's scary to me is that we heard similar rhetoric from Germany before WW1 and Japan before WW2.”

Funny he should mention World War I! Some social scientists consider that a paradigmatic example of nations leading the world to catastrophe through a misreading of each other’s intentions. President Theodore Roosevelt, in a letter he wrote a decade before war broke out, saw the dynamic at work:

[Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany] sincerely believes that the English are planning to attack him and smash his fleet, and perhaps join with France in a war to the death against him. As a matter of fact, the English harbor no such intentions, but are themselves in a condition of panic [and] terror lest the Kaiser secretly intend to form an alliance against them with France or Russia, or both, to destroy their fleet and blot out the British Empire from the map! It is as funny a case as I have ever seen of mutual distrust and fear bringing two peoples to the verge of war.

That quote can be found in the book Perception and Misperception in International Politics by the late Robert Jervis, a political scientist who studied the “security dilemma.” That term refers to the fact that what one nation does for defensive purposes is often seen as an offensive threat by the nation it’s defending against. And since this perception of threat can lead to defensive measures that are then perceived by the other side as offensive, and this perception can lead the other side to… well, you get the picture: a spiral toward cataclysm.

Which highlights the importance of trying to see things from a perspective other than your country’s default perspective—and brings us back to Noah Smith:

When someone on Twitter suggested that Xi was reacting to the Biden administration’s attempt to “suppress China’s growth” (through, for example, severe restrictions on the export of advanced microchips to China) Smith replied, “the US is trying to suppress China's ability to build advanced weaponry. It doesn't care about suppressing China's growth, which is already slowing all on its own.”

That may be true, but one point of Jervis’s work is that if Americans want to prevent World War III, the question they need to ponder isn’t just what their country intends, but how China is reading those intentions. If Xi Jinping thinks the US has declared war on China’s economy—and that, more broadly, it is mounting a kind of offensive to thwart China’s legitimate aspirations—that may matter more than whether the US agrees.

So try to imagine that you’re Xi Jinping and the following things have happened over the past year:

1. Re Taiwan (which, remember, China still considers part of China—and which even the US doesn’t recognize as a sovereign nation): Within only the last three weeks, US officials have said the US will: (1) more than triple the number of US troops on Taiwan, where they train Taiwanese soldiers; (2) increase the number of Taiwanese troops sent to the US for training; and (3) send Taiwan another $600 million in weapons.

2. Re tech: The US has imposed the aforementioned sweeping restrictions on the export of advanced microchips and chip-making equipment to China—not only from the US but from other western countries the US has leverage over. These sanctions are already hurting China—and since they were announced there have been at least two more rounds of US sanctions, one of them part of Biden’s frenetic over-reaction to the balloon incident.

3. Re regional security: The US is expanding its military infrastructure in the Philippines (and will hold its first joint military exercise with the Philippines since 2015), expanding security cooperation with Japan, and strengthening military ties in various ways with various Pacific countries while negotiating such deals with other Pacific countries.

4. Re odd and gratuitous anti-Xi rhetoric: In his State of the Union Address, Biden said—no, actually, it was more like shouted—“Name me a world leader who’d change places with Xi Jinping. Name me one! Name me one!”

If you’re a normal human being and you’re American, your reaction to all this may be something like, “But none of these things reflect a US desire to attack China. And doesn’t the US have a right to do them?” Sure. But one takeaway from Jervis’s work is that if those kinds of considerations are the only restraints nations impose on their behavior, we may all be doomed. So you should, at a minimum, ask how your nation would react if China did a combination of things roughly equivalent to the list above.

Sixteen years ago this week, on March 10, 2007, Vladimir Putin delivered a speech at the Munich Security Conference in which he said that the United States “has overstepped its national borders in every way.” He complained about NATO expansion and about the fact that America had repeatedly violated international law by attacking other countries (something that, at that point, Russia under Putin had never done).

The next year the US and its allies declared that Ukraine and Georgia would become members of NATO. Within months, Russia was at war with Georgia.

Some western observers dismissed Putin’s speech as a temper tantrum. And it is now remembered by some as a declaration that Russia was breaking with the West. But a re-reading of the speech doesn’t support that interpretation. The speech was a warning—a warning that if the US didn’t change course “the number of serious mistakes will be multiplied.” It was also a window into how someone who controlled a large arsenal of nuclear weapons was seeing the world. Those kinds of windows are always potentially valuable.

Attention paid subscribers! This week we bring you a record-breaking three paid subscriber perks.

You can listen to Bob discuss this week’s Earthling items with NZN staffer Andrew Day. To access that conversation, click here or look for it (and the other two perks) in your paid subscriber podcast feed.

You can listen to Bob’s essay, “ChatGPT’s Epic Shortcoming,” in audio form. The original essay can be found (unlocked, for all to read) here.

Last but not least, you have early access to Bob’s conversation with science writer Ananyo Bhattacharya about his book on the mathematician John von Neumann.

Con artists are using an audio version of deepfakes to scam parents and grandparents.

Washington Post tech reporter Pranshu Verma writes about Canadian couples who received phone calls from loved ones in distress—or rather, from impostors deploying AI-generated voices that sounded like loved ones in distress. One elderly couple sent scammers $21,000 after their “son” said he was in jail for killing a US diplomat in a car crash.

Apparently the scammers had gotten samples of the son’s actual voice from YouTube. And if you add up all the people with near-kin whose voices can be found somewhere on social media, that’s… a lot of potential targets.

And that’s not the scariest part. Right now the role of artificial intelligence in these scams is confined to the generating of the fake voice. The brain behind the voice is still a human one—a con artist typing replies that the AI turns into sound waves. Imagine how profusely these scams—and other scams involving fake voices—can be deployed once chatbots are doing the “thinking.”

The Pentagon is urging the White House not to share evidence of Russian atrocities in Ukraine with the International Criminal Court. What’s going on here? Is Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin a Putin apologist?

No. But he does have one thing in common with “Putin apologists”—he’s taken a position that is really annoying Lindsey Graham. Here’s the background: