Earthling: Ukraine and the New Cold War

Plus: Smart and dumb sanctions; Ukraine arms bazaar; Elon Musk absolved, etc.

Cold War II may turn out to look more like Cold War I than seemed possible only a few weeks ago. The Ukraine war has deepened the fissure between the West and Russia (a fissure that is of course well to the east of the first cold war’s borderline) in at least two ways.

First, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has galvanized and consolidated anti-Russia sentiment in Europe. Germany, with Europe’s biggest economy, played a pivotal role. Long reluctant to join in strong opposition against Moscow, Berlin this week announced not only that it would send weapons to Ukraine but that it would dramatically increase annual defense spending. The entire EU then announced that it would provide weapons to Ukraine—a decision that required unanimity among its 27 member states.

Second, the US-led sanctions regime, along with its aftereffects, is sharply reducing the flow of people and commerce between Russia and the West.

The sense of utter separation from Russian experience that Americans felt during the first cold war—a sense that people born since then may have trouble imagining—probably can’t return, thanks largely to the digital technologies that those people grew up with. (As of now, at least, I can still have Zoom calls with Russians—like this conversation I had right before the invasion with Nikita Petrov, who has for years worked for the Nonzero Foundation, which among other things publishes this newsletter.) Still, the sanctions are severing all kinds of non-zero-sum linkages that people in Russia and the West had come to take for granted and that together constituted significant and constructive interdependence. (As of this week, it’s not possible to send Nikita a paycheck—a problem for both of us.)

Of course, things can change; cold wars wax and wane in intensity. But the most-discussed scenario in which the West’s forceful response to the Ukraine invasion changes things in a good way—by triggering a palace coup that replaces Putin with someone more accommodating—would be, to say the least, a triple bank shot. And so far, notwithstanding the anti-war sentiment expressed by courageous Russians, there’s no good evidence that the Russian public broadly has turned against Putin.

Indeed, one poll found that Putin’s approval rating has risen from 60 to 71 percent. Take that with a grain of salt, as the poll was conducted by a state-owned research firm in Russia. But such results would be consistent with the “rally round the flag effect”—the fact that virtually any conflict with other nations raises a leader’s popularity, at least in the short run.

And maybe, in this case, in the long run. Kirill Federov, a resident of St Petersburg, told Al Jazeera, “Europe knows perfectly well that we did not elect Putin and our vote doesn’t count… By imposing sanctions that have affected ordinary people, they have shown even more that they are the enemy.”

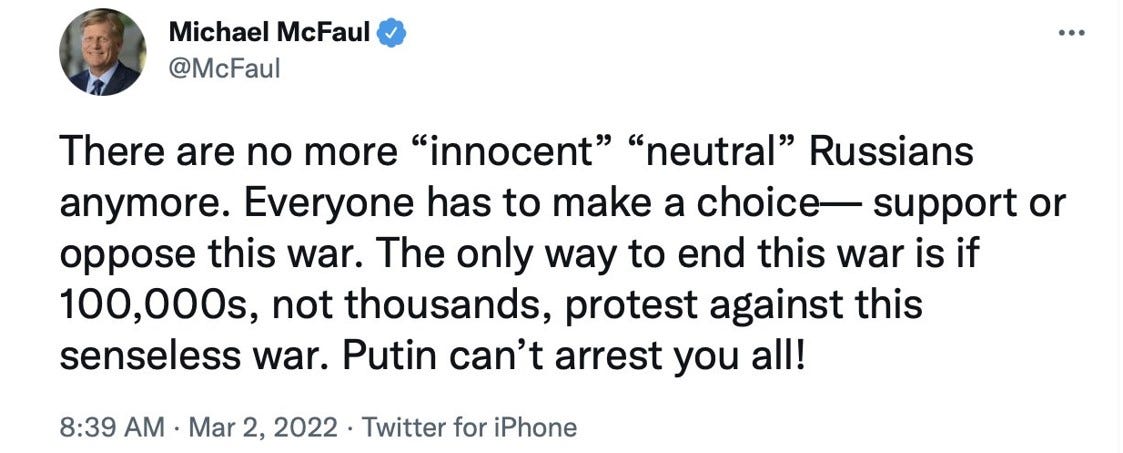

Meanwhile, as if to make sure that the Russian people consider the West the enemy, a former US Ambassador to Russia this week suggested that all Russians are morally responsible for Putin’s crimes unless they’re out on the street risking imprisonment to protest them:

McFaul, after much Twitter blowback, deleted this tweet and apologized. So maybe it’s unfair to dwell on this misstep—especially since I’ve taken McFaul to task more than once before.

But there’s a reason I keep bringing him up. He keeps saying things that are (IMHO) particularly glaring examples of the self-involved, nearly solipsistic, world view that has guided US foreign policy for decades.

It’s a world view that renders McFaul and other inhabitants of the Blob remarkably bad at seeing how things look from perspectives other than theirs. From such a vantage point it’s a mystery why good and decent people might choose not to risk everything they have by confronting a repressive authoritarian government; or why impoverishing a whole nation with sanctions might not endear its citizens to you.

I think McFaul is himself a good and decent person. That goes for pretty much everyone else in the Blob. But I do think the cognitive-empathy deficit shown by so many of them has played a big role in getting the world to its present state of precarious division. So I don’t think they’re the people we should count on to lead us to a better place.

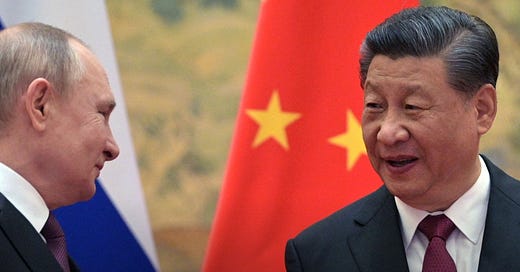

Meanwhile, on the eastern front of Cold War II, things are also icy—and may have been made icier by the Ukraine war. One reason is that the Ukraine invasion was immediately preceded by a high-profile display of solidarity between Russia and China. Putin and Xi Jin Ping met at the Beijing Olympics and emerged to issue a joint statement that, while not mentioning Ukraine, did call for an end to NATO expansion and did say the two countries’ friendship has “no limits.” This prelude to the invasion has linked the invasion to China in the minds of many westerners.

The Wall Street Journal reported this week that Xi isn’t happy about the invasion, in part because of this linkage. But the Journal also explained that the Xi-Putin bonding in Beijing was partly a product of something that probably won’t change soon—the Biden administration’s repeated demonstration of what China considers disrespectful or otherwise antagonistic behavior. In the months leading up to the Olympic display of Sino-Russian friendship, the Journal reports: