Earthling: Ukraine's demographic fault lines

Plus: Putin's brain, war and free speech, non-overlord robots, etc.

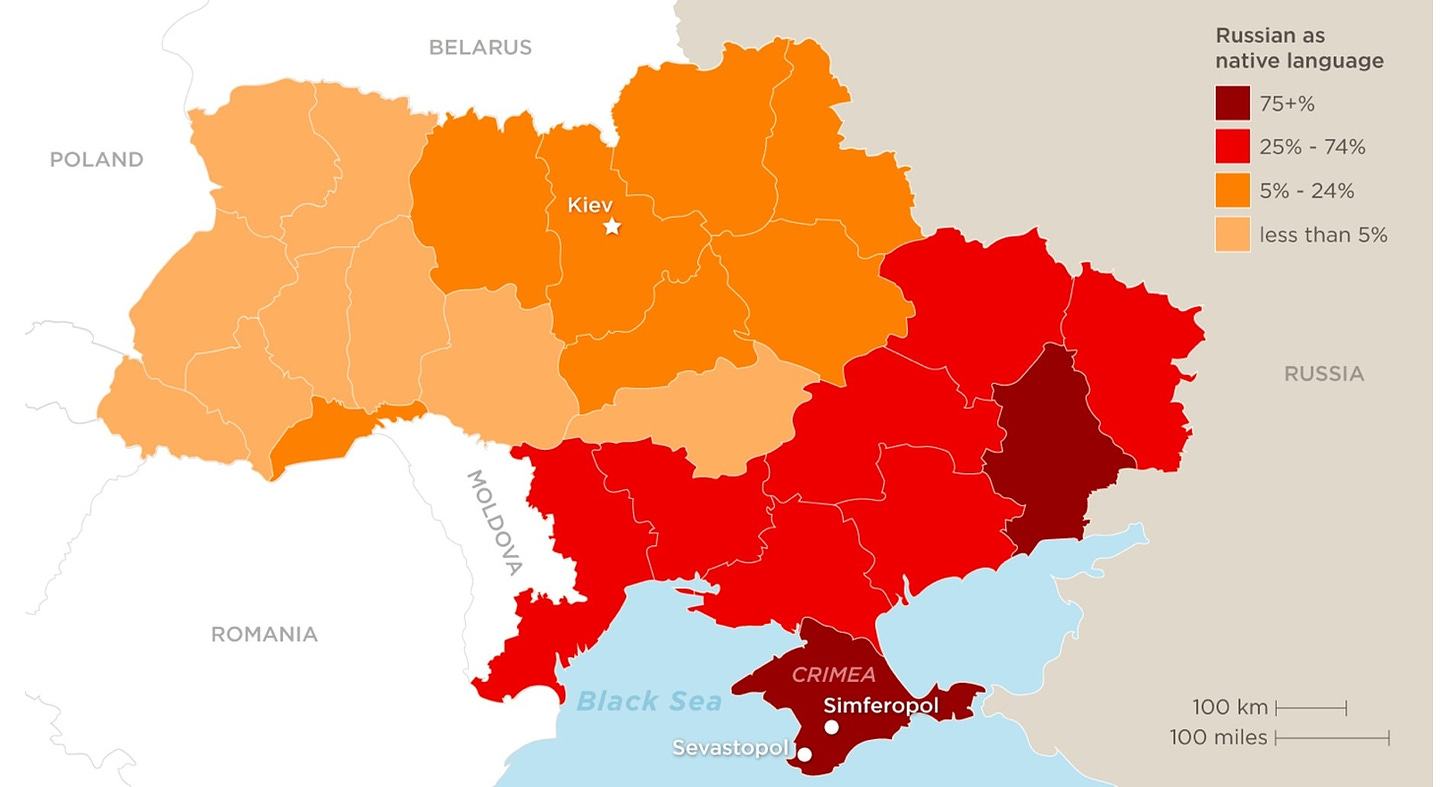

Demographics can play a big role in history, and the next phase of Ukraine’s history may turn out to be a good example. The two maps below put a finer point on that. Most of Ukraine’s citizens are native speakers of Ukrainian, but about a third are native Russian speakers (and a large number in both categories are fluent in both languages). In recent years the former have increasingly expressed a distinctly Ukrainian, and often pro-Western, ethnic identity, while many of the latter have felt alienated by a government in Kiev that they see as anti-Russian. Language maps like the one below can therefore shed light on such questions as: (1) where in Ukraine Russia would find it easiest to maintain an occupying military force, and where occupation could pose the greatest risk of insurgency; (2) where, in the event that Ukraine gets divided into two countries, or partially annexed by Russia, the boundary might be drawn.

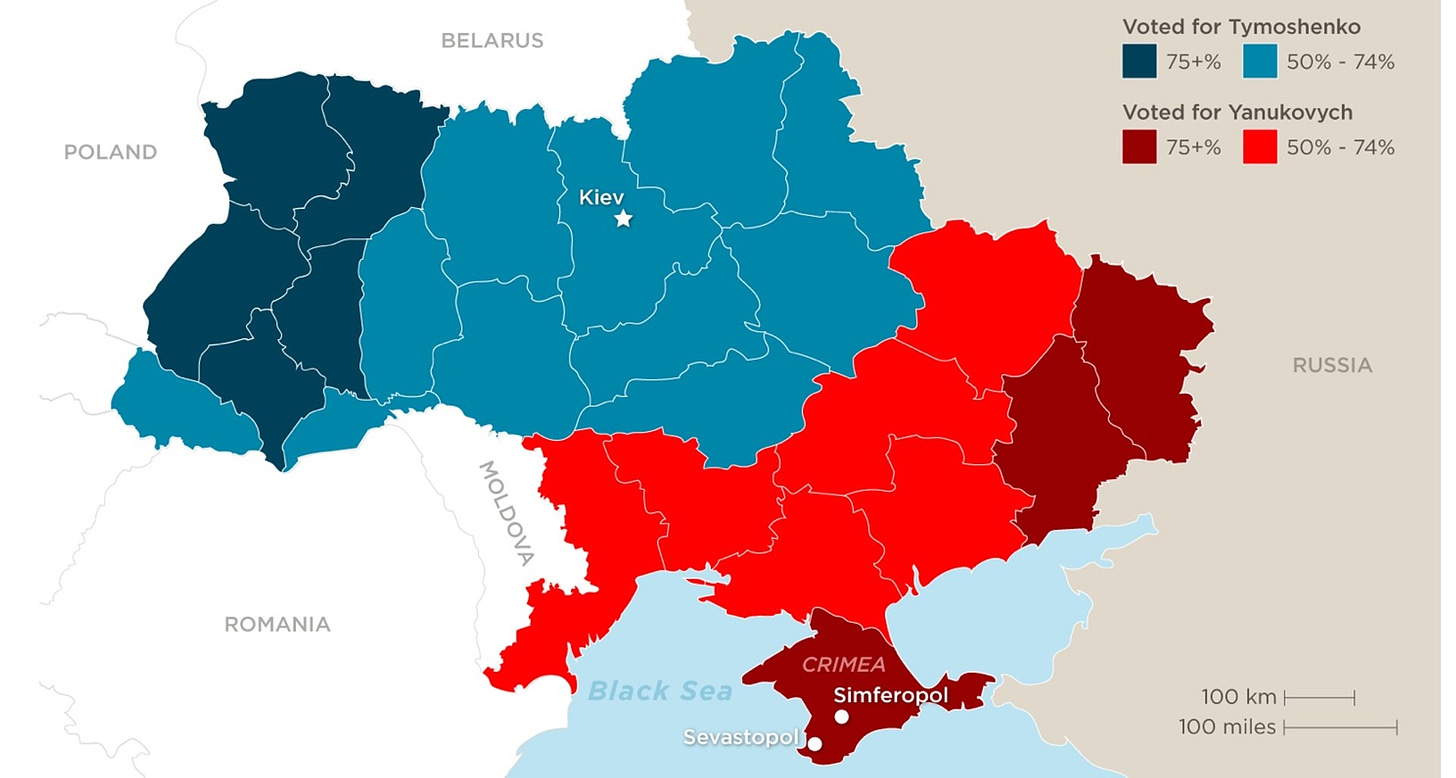

One way to see the political significance of the Ukrainian and Russian ethnic identities is to compare the map above with a map of voting patterns, below. It depicts the levels of support, during Ukraine’s 2010 presidential election, for the pro-Russian former Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych and the pro-NATO Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko.

Yanukovych won the election, but he was deposed in the 2014 “dignity revolution” (which the US played a role in, greatly angering Putin, who seems to consider this transition of power a western-backed coup). After the revolution, parliament voted to make Ukrainian the sole national language and to revoke the right of provinces to designate Russian their official language. This law was eventually found unconstitutional, but other laws have since banned Russian-language instruction in the schools. Legislation passed in 2019 banned Russian-language-only online stores and compelled workers in shops, restaurants, and other service outlets to address customers in Ukrainian unless the customer asks them to switch to Russian. That law, which drew protests from Moscow, was favored by 62 percent of Ukrainians and opposed by 28 percent—roughly the ratio of ethnic Ukrainians to ethnic Russians. Putin emphasizes these kinds of laws when he’s arguing that ethnic Russians are persecuted by the Ukrainian government.

After Vladimir Putin’s emotional and unsettling pre-invasion speech Monday—the one in which he said that Ukraine isn’t a real country—this thought crossed many minds: What the hell is going on inside Putin’s head? For months he’d been saying his grievances against the West were grounded in national security calculations—the encroachment of NATO on Russia’s borders, the placement of missiles in NATO member states, etc. But on Monday he didn’t sound cool and calculating, and he didn’t spend much time talking about NATO. He sounded like he was in the grip of simmering discontents about events dating back to the dissolution of the Soviet Union and even before. So does that mean this invasion wasn’t about NATO and national security?

I just recorded a conversation with a scholar whose work points to a possible answer. Steven Ward, a political scientist at Cambridge, is the author of Status and the Challenge of Rising Powers—and, as the title of the book suggests, he thinks the psychology of status is an important factor in international relations. For example: If nations aren’t treated with as much respect as they consider appropriate, they may get disruptive; and in some cases that’s partly because the nation’s leader takes the perceived disrespect personally. Integrating this idea into a grand unified theory of Putin’s brain—a theory that could explain his Monday performance—is a job for another day (I may tackle it in Monday’s newsletter, unless other Ukraine-related questions seem more compelling). But paid newsletter subscribers can listen to, or watch, my conversation with Ward now, and it will be publicly available on the Wright Show podcast feed by Tuesday. Meanwhile I’ll leave you with this partial plot spoiler: the expansion of NATO is seen by Russian elites both as a national security threat and as a sign of disrespect, and it’s not the only thing America has done that falls into both categories.

The world now produces twice as much plastic waste as it did only 20 years ago--and only 9 percent of it gets recycled. That’s the conclusion of the OECD’s first Global Plastics Outlook, which was released ahead of upcoming talks at the UN about a treaty to address the problem.