Pop quiz! First question: What do Elon Musk and the stewards of US foreign policy have in common?

If you answered “a lack of cognitive empathy,” you don’t get any credit—not because that isn’t a correct answer (I think it is, more or less) but because it’s such an obvious answer. After all, cognitive empathy (aka “perspective taking”) is a known obsession of this newsletter, and complaining that people don’t show enough of it is one of my favorite pastimes.

So on to the second, more challenging, question: What else do Elon Musk and the stewards of US foreign policy have in common? Hint: It’s something that may explain their lack of cognitive empathy.

Before unveiling the answer, let’s nail down this “lack of cognitive empathy” indictment:

This week Musk, shortly after becoming Twitter’s owner, posted a tweet that (a) suggested that the official story about the guy who attacked Nancy Pelosi’s husband (that he was a crazed Nancy Pelosi hater) might not be the real story, and (b) linked to a semi-coherent post on a disreputable website suggesting that Mr. Pelosi’s attacker was actually his gay lover or a male prostitute paying a house call or something like that.

Musk eventually deleted the tweet, which is a kind of acknowledgment that he hadn’t done a good job of anticipating the reaction to it—acknowledgment, in other words, that he hadn’t skillfully exercised cognitive empathy. There are also subtle signs of cognitive empathy deficit in the particular wording of Musk’s tweet, which we’ll get back to.

And, this tweet aside, there are tons of Musk tweets that seem to evince obliviousness to how they’ll be received by large numbers of people. Now, I realize we can’t rule out the possibility that Musk just doesn’t care how they’re received (or that he cares only in the sense of actively enjoying the blowback). But one point of this piece is going to be that the line between not understanding how other people see things and not caring how other people see things is fuzzier than you might think.

As for the second cognitive empathy deficit indictment—indictment of the stewards of US foreign policy: Rather than republish a litany of their momentous failures to take account of the perspectives of foreign actors and foreign audiences, I’ll add a new litany item. Here it is:

In last week’s NZN I compared the challenges of deploying cognitive empathy toward Putin and toward Hitler. I asked how much you’d have to correctly surmise about each man’s psychology to predict that (1) Putin would invade Ukraine or (2) Hitler wouldn’t be appeased by the 1938 Munich concessions. In the course of that I riffed on several seemingly relevant factors in Putin’s psychology. A newsletter subscriber who lives in Russia then suggested an additional factor that may have inclined Putin to invade. One view that is “quite popular here in Russia,” he said, is that “western elites are trying to dominate the world” through military and commercial means—and that, since this makes a confrontation with Russia inevitable, Russia might as well strike first.

I’ve paid pretty close attention to the discourse of American foreign policy elites since the Ukraine invasion, and I’ve seen few if any signs of awareness on their part that this kind of sentiment may be widespread in Russia. I’ve seen, in short, a lack of cognitive empathy (assuming that this NZN reader’s account is accurate—and I’ve seen other evidence that it is).

So, anyway, what’s the answer to question number two? What do Elon Musk and stewards of US foreign policy have in common that could explain their seeming lack of cognitive empathy? Well, there is evidence, in the annals of social psychology, that feeling powerful impedes cognitive empathy. And one thing Elon Musk has in common with those stewards is a sense (well founded in both cases) that great power is at their disposal.

This idea—that having power is what explains these apparent cognitive empathy deficits—is just a hypothesis, and a conjectural one at that. And it has a better chance of applying to the foreign policy stewards than to Musk, because in Musk’s case there is an obvious alternative explanation. Musk has said he has Asperger’s syndrome (aka autism spectrum disorder, or ASD), which has been linked to deficits in cognitive empathy. (When Musk mentioned his ASD during a Saturday Night Live monologue, he also jokingly apologized for his offensive tweets—which suggests he sees a connection between the two; “that’s just how my brain works,” he said about his tweets.)

Whatever the merits of these two conjectural applications of the idea that power can impede cognitive empathy—and whatever the merits of the social psych theory that power does impede cognitive empathy—it’s important to understand why the theory makes sense. The human mind was engineered by natural selection, complete with mechanisms for negotiating complex and changing social landscapes. Those mechanisms include cognitive empathy, but they also seem to include switches that turn the cognitive empathy off and on, depending on circumstance. Natural selection giveth, and natural selection taketh away, and the more we understand about the implications of this, the better.

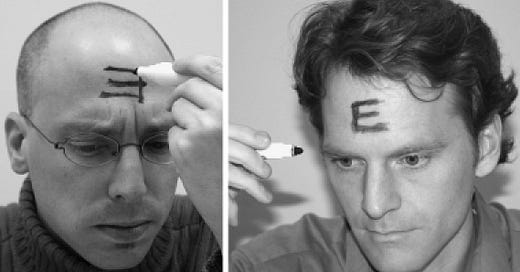

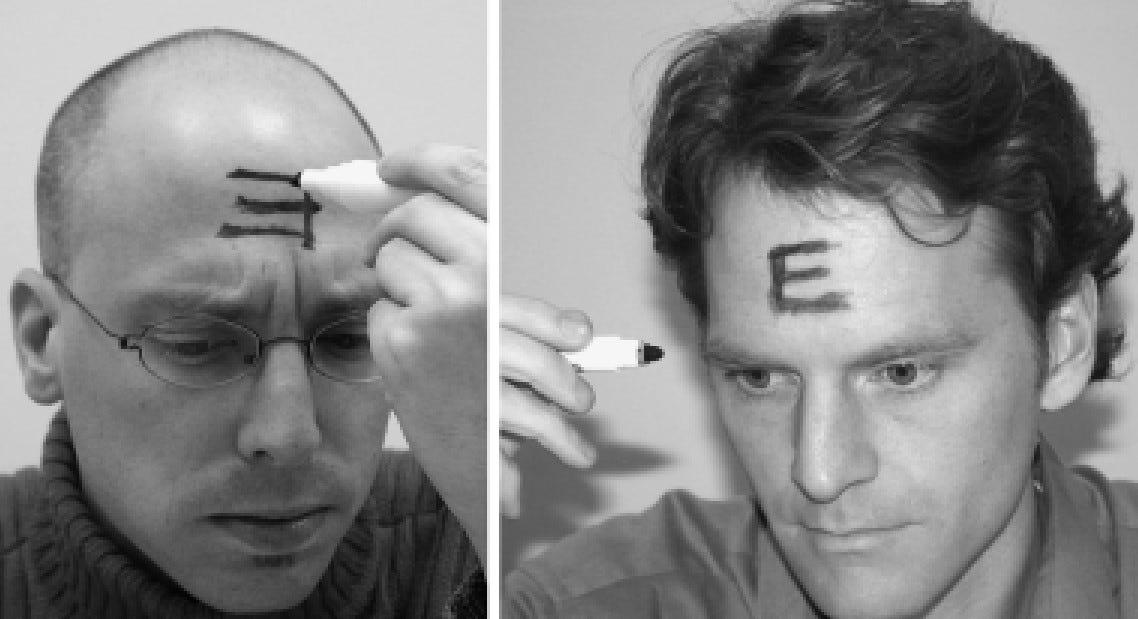

Let’s look at a much-cited series of experiments exploring the connection between power and cognitive empathy that were reported by the psychologist Adam Galinsky and three other scholars in the journal Psychological Science in 2006. (A picture that appeared in their article is above.) Here’s the basic structure of the experiments: