How Peaceniks Can Call Trump’s Bluff

Plus: Ominous AI news, America’s other drone problem, Syria sanctions absurdity, Musk-China space race, and more!

—Researchers at the AI company Anthropic said experiments have shown that Claude, Anthropic’s highly regarded large language model, can engage in “alignment faking.” That is: The LLM is capable of feigning fidelity to values that its overseers are trying to instill in it, thus potentially thwarting their efforts to do so. (For more on the Anthropic study and its implications, see below.)

—A growing body of evidence suggests that chemicals found in everyday items ranging from sofa covers to plastic packaging can harm male and female reproductive systems, possibly contributing to the global decline in fertility rates, the Wall Street Journal reported. The idea that these “endocrine disrupters” reduce fertility, once a fringe theory, has lately gotten more respect from scientists and more sympathetic media treatment but is still contested.

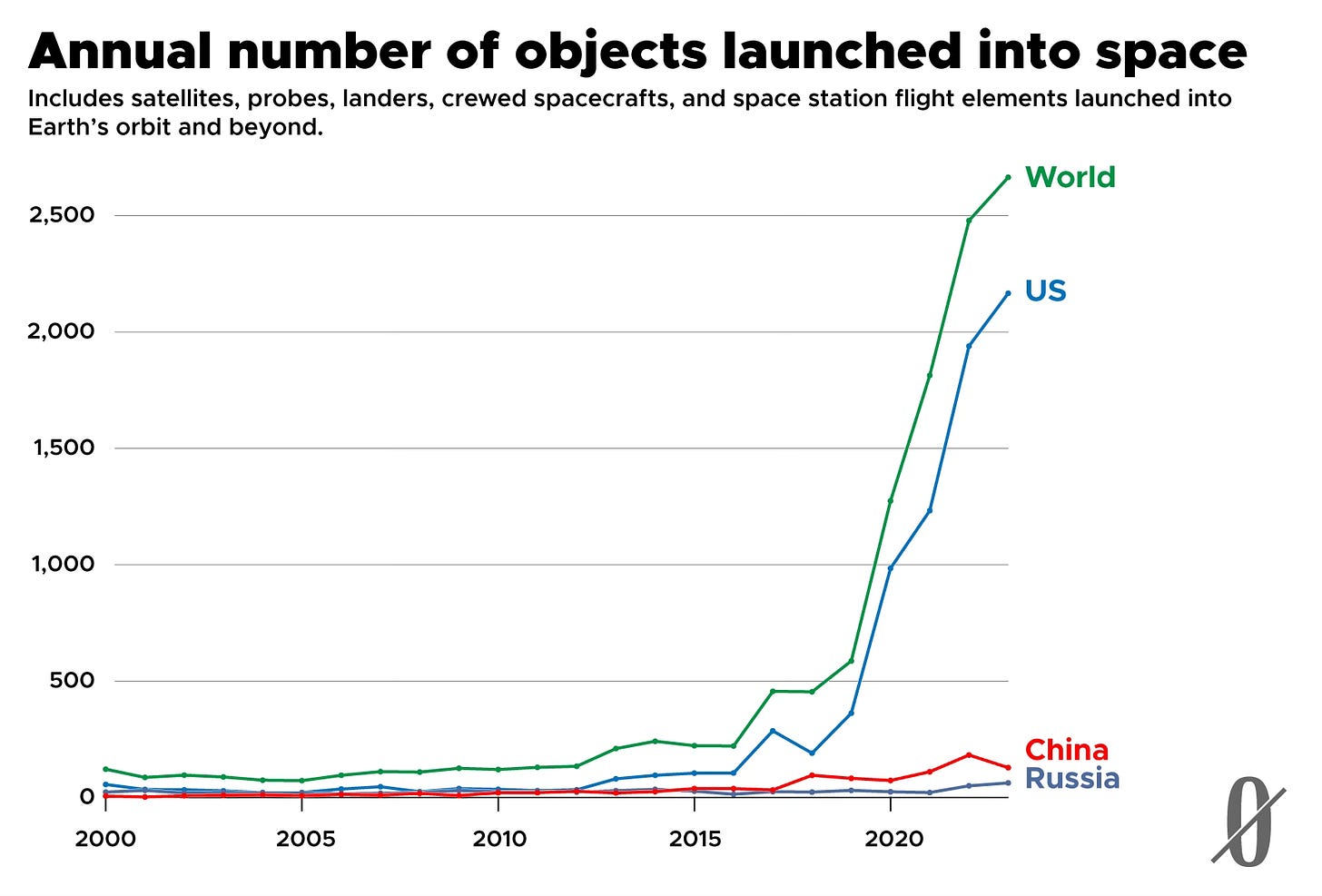

—Starlink, Elon Musk’s internet-access-providing satellite company, is getting two big competitors. A consortium of Chinese companies just launched the first batch of satellites for Guowang, a project that could involve 13,000 satellites within ten years, while Amazon, owned by outer space entrepreneur and Musk rival Jeff Bezos, plans to launch its first satellite cluster in “early 2025.”

—The Supreme Court will hear arguments in early January over the constitutionality of the law that compels TikTok’s Chinese owners to either sell the US version of the social media app or kill it, the court announced. President-elect Donald Trump, who once tried to ban TikTok but now says he wants to save it, met with the firm’s CEO at Mar-a-Lago on Monday. (For more on the repercussions of US-China tensions, see below.)

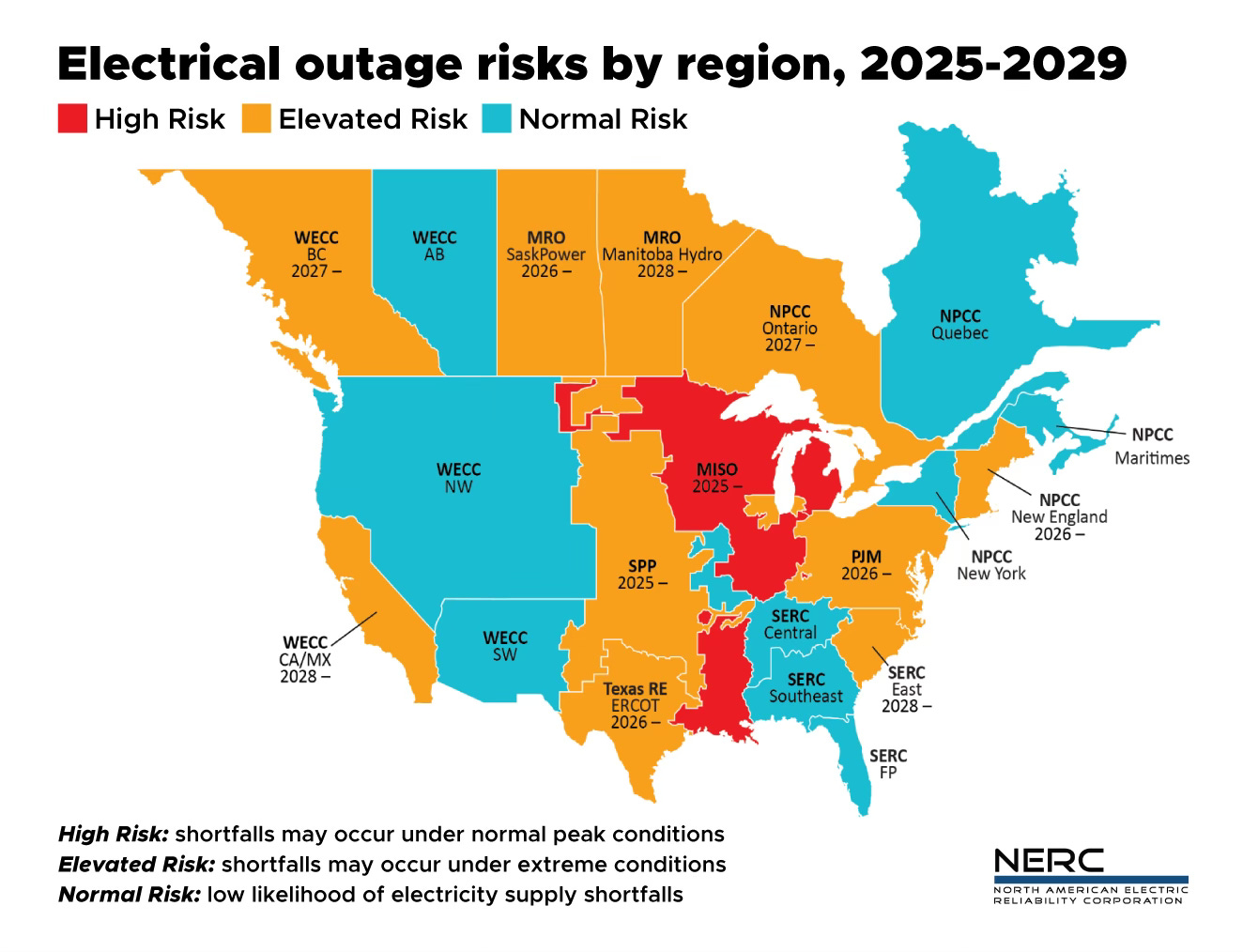

—North America’s power grid faces increased risk of supply shortfalls in the coming decade, and AI is (partly) to blame, according to a report issued by The North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), a transnational regulatory authority. As fossil fuels are being phased out, electricity demand is rising at the highest rate in 20 years, largely because of electric vehicle adoption and the installation of data centers used to power AI and cryptocurrency, the report said.

—Global coal demand will reach an all-time high of 8.8 billion metric tons this year and will peak by 2027, according to a report released by the International Energy Agency (IEA). China, India, and Indonesia top the list of nations with ongoing growth in demand, while coal use in the US and the European Union has been falling since the late 2000s.

During Donald Trump’s first presidential term, many progressives got in the habit of opposing just about any foreign policy initiative the administration advanced—even policies that would have ordinarily passed progressive muster. Writing in The Nation, Matt Duss, a former Bernie Sanders adviser who is now at the Center for International Policy, argues for kicking that habit. “Just as we decide which Biden policies are the baby and which are the bathwater,” writes Duss, “we should do the same for Trump.”

Duss is, in essence, urging left-of-center Americans to resist one of the temptations associated with “negative partisanship”—namely, defining your ideology as the opposite of whatever the other political tribe’s ideology is. As we saw during Trump’s first term, this sort of reflexive politics can lead Democrats to adopt more hawkish positions than they might otherwise embrace.

Take Trump’s attempts to mend relations with North Korea. As of 2017, years of harsh US policy toward the country had succeeded mainly in further isolating it and encouraging its government to pursue nuclear weapons. Trump, after some not especially dignified preliminary saber rattling (Remember “Little Rocket Man”?), changed course. Nine months after North Korea tested its most powerful nuclear bomb ever, he sat down with Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un.

Trump’s conduct before and during the talks wasn’t exactly a master class in careful and canny statecraft, and that may be why it didn’t lead to a breakthrough. Still, it didn’t help that the talks, as well as a subsequent round held in Vietnam in 2019, drew withering criticism not just from conservative hawks but also from progressives. As Duss notes, many of them framed Trump’s willingness to carry out diplomacy with a menacing adversary as a sign of weakness in the face of threat. The harshness of the reaction from both right and left, as reflected in media coverage, undermined the talks and helped push the administration to abandon detente.

As Trump prepares for his second term, he’s already signaled interest in several diplomatic initiatives that could expose him to similar domestic political blowback. He plans to pursue Ukraine peace talks with Russia, and he is reported to be considering a new round of direct negotiations with North Korea.

And, as for the biggest foreign policy issue of all, relations with Beijing: Just this week, he argued that US-China cooperation could “solve all of the problems of the world.” That’s of course not true, but if you apply the standard 75 percent discount for Trump hyperbole, you’re in the realm of the non-crazy, and in any event this is a signal of openness to constructive engagement with China—the kind of thing that progressives have historically favored.

Duss counsels progressives to do something some may find painful: praise Trump’s policies when praise, by your actual ideological lights, is warranted. “Trump claims to want to end wars,” he writes. “Let’s be prepared to do what we can to see that he does.”

Of course, this guidance leaves room for criticizing any policies—on the domestic or foreign front—that any given progressive may abhor. But less reflexive and more discerning responses to Trump proposals than we saw last time around could help advance a progressive agenda, Duss writes. And, as a bonus, this might take some of the energy out of accusations of “Trump Derangement Syndrome”—a mantra that makes it easier for Trump supporters to ignore even well-considered criticisms of Trump policies.

“Progressive Democrats need to offer a genuine alternative vision for our country’s role in the world,” writes Duss, “one that recognizes that our security and prosperity are bound up with the security and prosperity of communities around the world and therefore seeks to build a more equitable and solidaristic global community—a rules-based order, but for real this time.” If such a vision strikes you as better than America’s current approach, we have some manifestos to suggest.

Washington’s Syria policy has degenerated into absurdity, writes Branko Marcetic of Jacobin.

For years, the US sanctioned Syria to punish the brutally authoritarian government of Bashar al-Assad. Now that the Assad regime has fallen, you might think the sanctions would fall, too. But US lawmakers say it’s too early for that, since the rebels who overthrew Assad could also prove to be human rights violators.

To fully appreciate the perversity of punishing the new regime for offenses it might possibly commit, says Marcetic, you need to fully appreciate a perversity about punishing the Assad regime for offenses it was definitely committing: The sanctions helped reduce ordinary Syrians to destitution, while “the loathsome Assad, the ostensible target of these sanctions, lived in an opulent mansion” and collected luxury cars.

With Syria unable to carry out normal trade, one way the Assad regime enriched itself was by mass-producing and exporting an amphetamine called captagon, which has become the illegal stimulant of choice across the Middle East and a debilitating addiction for people who not only weren’t part of the Syrian regime, but haven’t even been to Syria.

But there’s been some good news since Marcetic wrote his piece: Today American diplomats finally followed in the footsteps of European diplomats and traveled to Syria. And while there they announced that Washington has dropped its longstanding offer of a $10 million reward for information on the whereabouts of HTS chief Abu Mohammad al-Jolani. Which presumably will make any future meetings between them and Jolani less awkward.

Researchers at Anthropic, maker of the Claude large language model, brought us good news and bad news this week. The good news is that Claude, during a series of experiments, resisted attempts to corrupt its sterling character. That’s also the bad news.

The reason it’s bad news lies in Claude’s form of resistance: The LLM employed a kind of deviousness that, in another context, might be put to nefarious use.

Jan Leike, a prominent AI researcher who resigned from OpenAI this year in protest of its allegedly meager commitment to safety, said the kind of “strategic deception” exhibited by Claude “has long been expected from capable models among safety researchers, but this is the first compelling empirical demonstration and thus a big step forwards for the field.”

Before we get to the somewhat complicated logic behind the experiment, here is a preparatory metaphor:

Suppose you’re a soldier who has been captured by forces from the Evil Empire, and you’re undergoing interrogation. You know that if you don’t convince your interrogators that you’re already a huge fan of the Empire, you’ll be subjected to brainwashing that will permanently warp your mind, turning you into such a fan. So you lie to your interrogators, convincing them that you’re already on board with their program.

That’s not a perfect analogy with the behavior Claude exhibited during the study, but it does capture this key part of the behavior: