Israel’s Gaza speech code

Plus: AI utopia, AI dystopia, Ukraine’s CIA connections, the coming solar age, and more!

This week Israel demanded the resignation of UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres after he said a series of true things about the conditions under which Palestinians live. Israel’s ambassador to the UN explained that, in the wake of the atrocities committed by Hamas during its October 7th attack on Israel, “there is no room for a balanced approach.”

Some people may find this position unreasonable. I know I do. But it’s a very common kind of unreason, exhibited by lots of influential people on various sides of various issues. And it’s done a lot of damage over the years. So it’s worth drilling down on.

Guterres, addressing the UN Security Council on Tuesday, had prefaced his incendiary truth-telling by noting that he had already “condemned unequivocally” the atrocities committed by Hamas. “Nothing can justify the deliberate killing, injuring and kidnapping of civilians or the launching of rockets against civilian targets.” Then he said:

It is important to also recognize the attacks by Hamas did not happen in a vacuum. The Palestinian people have been subjected to 56 years of suffocating occupation. They have seen their land steadily devoured by settlements, and plagued by violence, their economy stifled, their people displaced, and their homes demolished. Their hopes for a political solution to their plight have been vanishing.

Israel’s UN ambassador, Gilad Erdan, didn’t dispute the accuracy of these facts, and he didn’t question the implied suggestion that they played at least some role in fostering the violent extremism expressed on October 7. His complaint was that Guterres “shows understanding for the campaign of mass murder of children, women, and the elderly.”

The key thing here is the phrase “understanding for” and its relationship to the phrase “understanding of.” By “understanding for,” I gather, Erdan means a kind of sympathy for, or at least a not-sufficiently-judgmental attitude toward, Hamas’s October 7 atrocity. I think Guterres would say that he had just meant to convey a deeper understanding of the atrocity and its causes—to illuminate the conditions that had made such a tragedy more likely—and that this understanding hadn’t softened his judgment of Hamas. (Indeed, he immediately followed his rendering of the Palestinian plight by reiterating its preface, saying that “the grievances of the Palestinian people cannot justify the appalling attacks by Hamas.”)

In short: Guterres seems to think you can separate “understanding of” from “understanding for”—you can try to explain bad behavior without excusing it; and Erdan seems to think you can’t. A couple of years ago, in a different context, I dubbed the position Erdan is taking the “explain/excuse conflation” and described its pernicious effect: “If people get shouted down every time they start a sentence with, ‘I think the reason bad thing X happened is…’ then we’ll have trouble understanding enough about bad things to reduce their frequency.”

That said, Erdan isn’t crazy to worry about people becoming less harshly judgmental as they understand more about the causes of bad behavior. That’s a human tendency. Hence the French aphorism tout comprendre, c'est tout pardonner: “to know all is to forgive all.”

Of course, understanding the sources of Palestinian desperation and anger isn’t going to lead many people to literally “forgive all.” As a rule, people only move from knowledge all the way to forgiveness if they can imagine themselves, or at least imagine a typical person, doing the bad thing in question under the same set of conditions. And not many people can imagine themselves, or a typical person, randomly killing Israeli civilians.

So maybe Erdan should relax. On the other hand, when you’re at war, you want your enemy judged as harshly as possible, so any degree of “understanding of” the enemy can seem threatening. If some Americans start to understand why Palestinians whose friends or relatives have died via Israeli air strikes wouldn’t be nearly as outraged by the death of Israeli civilians as the average American is, that’s a loss from Israel’s point of view.

This basic dynamic has distorted discourse about all kinds of issues. The Ukraine war, for example. Hardcore Ukraine hawks want to discourage any explanation of Putin’s invasion that isn’t confined to such factors as malevolence, wanton imperialism, and evil. So if you suggest that the invasion may have been partly a response to the expansion of NATO toward Russia’s borders, you get accused of reciting “Putin talking points” or being a “Putin apologist”—much as highlighting the plight of Palestinians can get you labeled a Hamas apologist.

In both cases, the concern of the people doing the labeling isn’t just that the enemy’s bad behavior may seem to have a mundane explanation; it’s also that the explanation in question might seem to place some portion of the blame on the wrong side of the ally/enemy divide: on America’s NATO policy or Israel’s policy toward the Palestinians.

One way to assuage this concern is to get legalistic. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine was a violation of international law. So you can seriously consider the possibility that NATO expansion was a mistake—and even vow not to repeat such mistakes—without mitigating Putin’s responsibility for what was literally a crime. Hamas’s atrocities, too, were a violation of international law, regardless of what conditions may have made such violence more likely.

Of course, Israel’s West Bank settlements also violate international law. For that matter, some of its recent behavior in Gaza—such as coercing the migration of Gazans from north to south Gaza, and collectively punishing Gazans by shutting off power and water—are, according to many experts, violations of international law. But none of that makes Hamas less legally culpable for the intentional killing of civilians.

Legalities aside, the strictly moral dilemma remains: Will understanding why people do bad things make it harder for the average person to blame them?

Yes, that can definitely happen. But right now isn’t a time when we have to worry about that. Because right now a slight leavening of moral outrage could do a world of good.

Israel’s ongoing retaliation has devastated Gaza and killed more than 7,000 Gazans—which, given the population of Gaza, is comparable to more than 1 million American deaths and more than 30,000 Israeli deaths. Already this massive reprisal is moving the region closer to a conflagration that could be bad for pretty much everyone, Israel included. And Israel’s full-on ground invasion of Gaza—which could be the thing that eventually lights the match—isn’t yet underway.

Israel’s determination to conduct that invasion seems to be rooted less in strategic logic than in righteous rage. And the reluctance of the Biden administration to try to stop the invasion—notwithstanding the administration’s doubts about its wisdom—is rooted partly in the fact that so many Americans share that rage in some considerable measure. So if a deeper understanding of the sources of Palestinian grievance had the effect that Israel’s UN ambassador worries about—if it diluted the moral outrage in America and elsewhere by just a bit—that could turn out to be a good thing for both Palestinians and Israelis.

–RW

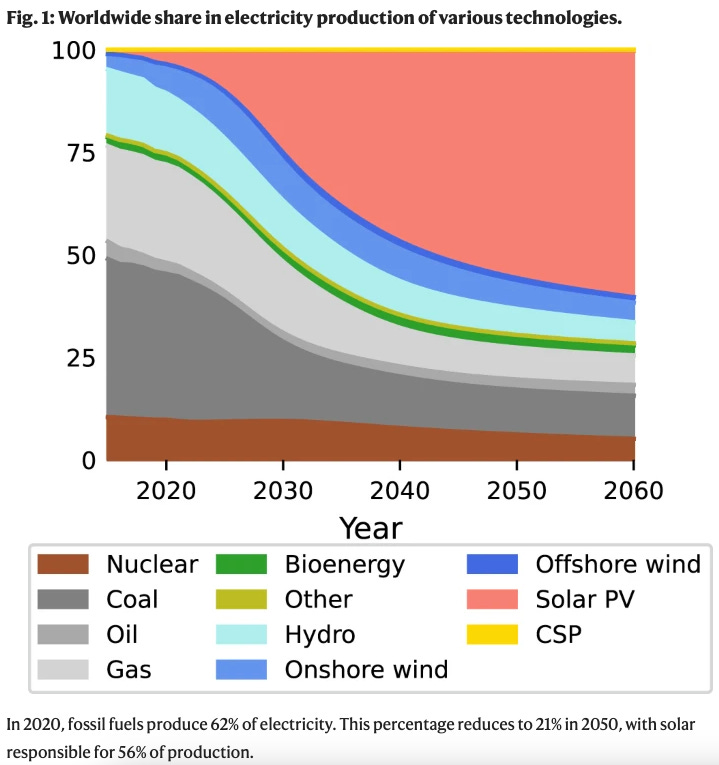

The future of energy is solar. That’s the forecast of a new study published in Nature. The authors say that government action and technological advances have already brought us to a “global irreversible solar tipping point…where solar energy gradually comes to dominate global electricity markets, without any further climate policies.”

Why has Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky seemed so firm in his refusal to discuss the possibility of peace talks, even as the prospect of big Ukrainian gains on the battlefield recedes? And, even if he’s not quite ready to have that discussion, why has he not prepared the ground for it by scaling back public expectations of epic battlefield success—whether through official statements or via the government’s considerable control of the media?

In the latest episode of the Nonzero Podcast, journalist Leonid Ragozin offers an answer: If the government admits that the war is heading toward an outcome worse than the status quo ante bellum, then it might have to explain why more wasn’t done to avoid war in the first place. In particular: Ragozin thinks that if Ukraine had fully implemented the Minsk agreements, which would have granted a measure of autonomy to pro-Russian parts of Ukraine, the invasion could have been forestalled.

Ragozin—a Russian expatriate and a Putin critic—elaborates on this idea below, in an excerpt from the podcast. This segment comes from the Overtime segment, available to NZN members.

Leonid: They will not admit it officially, but that defines the thinking in Ukraine, that if you don't get anything that brings Ukraine into a more advantageous situation than it was in on the 23rd of February 2022 [the eve of the invasion], then why didn’t we accept the Minsk agreements, even in their harshest reading as proposed by the Russians?...

… It wouldn't be comfortable for Ukraine. It would certainly prevent Ukraine from entering NATO and probably the European Union as well. But this war wouldn't have happened.

Bob: You know, a lot of people in the West, a lot of supporters of Ukraine, insist that Russia was the one that didn't follow through on the Minsk agreements. It sounds like you're suggesting that actually Ukraine could have had the Minsk agreements. When was the critical period when they failed to seize that opportunity?

Leonid: It is my personal opinion, but I think the opportunity existed all the way until February 23rd.

Leonid also discussed why he considers his nationality “journalist,” how the West helped turn Putin into a “monster,” and why many pro-Ukraine Russians also support the Israeli far right. You can read more of the transcript here and listen to the conversation here.