Welcome to NZN’s year-end issue! Herein we (1) bring important news about the future of this newsletter (buried deep in the lead piece on Trump withdrawal syndrome—which, we humbly submit, is worth reading in its own right); (2) offer a searing critique of the Biden foreign policy team that doubles as a manifesto for progressive realism; and (3) steer you to readings on such subjects as: the downside of being Machiavellian, the pope’s war on tribalism, the booming ransomware business, and whether Wokism should shape vaccine distribution policy.

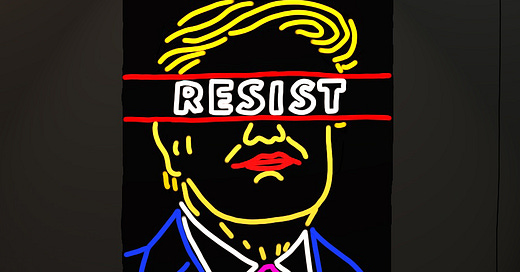

Trump withdrawal syndrome

The enduring attraction of war is this: Even with its destruction and its carnage it can give us what we long for in life. It can give us purpose, meaning, a reason for living... It gives us resolve, a cause. It allows us to be noble.

—Chris Hedges, War Is a Force that Gives Us Meaning

I got my first Trump withdrawal symptom a few weeks ago. It happened while I was listening to Steve Bannon’s podcast—which, I know, I know, I probably shouldn’t spend my time doing, but then again haven’t the last four years been, among other things, a story of almost all of us using media and social media in very suboptimal ways?

Anyway, Bannon’s podcast had become a kind of nerve center for the effort to overturn the results of the presidential election. So I was in the habit of tuning in to monitor the state of play—and also, I admit, because I find Bannon’s seedy charisma fascinating. You can say a lot of bad things about Bannon—that he’s dishonest, that he’s amoral, that his grooming habits could use an upgrade—but you can’t say he’s not a great demagogue.

Each day, in rants that are broadcast not just via YouTube and podcast apps but on hard-right media outlets like Newsmax TV, he rallies his grassroots army (”the deplorables,” he lovingly calls them), exuding boundless confidence in victory against the enemy—the “globalists,” the Democrats (“the party of Davos”), the “Biden crime family,” and so on.

So I was listening to the podcast one day and for a moment Bannon’s spirits seemed to sag, as if the accumulated weight of the legal and political setbacks suffered by the stop-the-steal movement had finally sunk in. Bannon uttered his ritual guarantee of victory—“We got this”—but for the first time it seemed to refer not to Trump’s victory in this election but to the eventual triumph of the movement Trump represents.

Or maybe I was reading too much into it. Certainly Bannon quickly regained his verve; he continues to profess confidence that Trump will be a two-term president. But in that fleeting moment of flagging Bannon energy, I suddenly imagined a day—soon, God willing—when the Trump presidency would be in the rear-view mirror.

My first reaction was relief. Then came the symptom.

It wasn’t a feeling of emptiness, exactly. It was just a momentary lack of orientation, and of motivation. Like: So what do I do next? For four years what seemed like an existential struggle has been playing out on media, on social media, and (before the pandemic) in chance conversations. I might get distracted from it for a while, but the battle was always there, like barely perceptible background music that I could turn up whenever my life seemed low on significance. Or when I just needed an excuse to procrastinate.

Obviously, participating in this war had its downsides, including not-wholly-pleasant emotions such as rage, fear, and hatred. Also, there was that unsettling American-republic-teetering-on-the-brink-of-collapse thing. Still, the last four years gave many of us a sense of purpose and the kind of deep camaraderie that is found only in opposition—against armies on a battlefield, against teams on an athletic field, against… Trump.

And that explains the grim realization that dawned on me during Steve Bannon’s momentary lapse of confidence: I was going to miss Bannon. And I was going to miss the war against Trump. At some level, you probably will too.

So what do we do on January 20, when Trump is finally dragged off stage?

Option 1: Just keep doing what you’ve been doing. If you don’t want to kick your Trump habit, you don’t have to. After Trump has left the White House he’ll continue to indulge his own addiction—to attention—by trolling us via Twitter and other avenues. If you want to stay tuned to Trump and react as you’re accustomed to reacting—with raw outrage, with bitter denunciation, with cool, righteous sarcasm, whatever—he will be happy to facilitate that.

But remember: Your outrage is Trump’s fuel. The more visibly hated he is, the more his fans love him. So if you really hate him—if you’d give anything to see his stature drop and his influence wane and his ego sustain grave damage—then your best bet is to ignore him and encourage your friends to do the same. #UnfollowRealDonaldTrump.

Of course, this would leave a Trump-sized hole in your life. Hence:

Option 2: Take up gardening. Or handicrafts or video games or golf or whatever. In other words: change the channel. You might even consider staying off social media for a while—or, failing that, reconfiguring your social media feed so that it shows you a lot of stuff about… gardening or handicrafts or video games or golf.

But if changing the channel doesn’t work—if you keep feeling the lust for battle—there’s this:

Option 3: Keep fighting the fight. But rather than think of the fight as being against Trump, think of it as being against Trumpism. This is not an original idea. Various people have warned that the threat of Trumpism will persist once Trump has finally left the oval office. But they don’t always define what they mean by Trumpism. So:

By Trumpism I don’t mean any movement that advocates policies Trump claimed to represent—like tighter restrictions on imports and immigration. Reasonable people can disagree about these things, and you can imagine a populist movement that favored high tariffs and low immigration quotas and was a wholesome part of the political conversation.

By Trumpism I mean a kind of populism that is inherently unwholesome—a movement that gravitates toward a leader who is proudly cruel, flagrantly dishonest, vaguely authoritarian, and contemptuous of laws and norms that sustain democracy; a leader who brings out some of the worst parts of human nature in his followers and, ultimately, in his opponents. Defeating Trumpism in America would mean creating a country in which this kind of populist leader wouldn’t get traction.

That’s a scarily big job, but, before you decide to shirk it in favor of gardening, consider this: you would be helping to save not only the country but the world. The things that fuel Trumpism—ranging from specific political grievances to generic dynamics of social media to generic dynamics of human psychology—fuel all kinds of trouble abroad: not just Trumpesque populist movements and their attendant antagonisms, but antagonisms of other kinds: between nations, between religious groups, between ethnic groups. The war against Trumpism is to some extent the war against tribalism and the war for global harmony, which is to say the war to save the world from various disasters that could afflict it if humankind doesn’t get serious about cooperating to avert them.

And for me personally, this war brings another bonus: it may mean I don’t have to say goodbye to Steve Bannon! Assuming Bannon’s Herculean effort to subvert democracy on Trump’s behalf is rewarded with a presidential pardon—so he doesn’t have to stand trial for grifting his beloved deplorables and can instead keep warping their minds via podcast—I’ll be tuning in, at least intermittently. I’ll keep trying to understand the nuances of his appeal to them, and the various forces (technological, sociological, psychological, political) that make them susceptible to his demagoguery. The long-term goal being, of course, to better understand how to undermine the appeal of Bannon and people like him.

But that’s just me. Different people can fight the war—the war to undermine Trumpism and tribalism and build international community—in different ways. This isn’t the time to enumerate all those ways (in part because I haven’t figured them all out). But regular readers of this newsletter know that I consider them to include things ranging from in-the-weeds policy nerdism (especially foreign policy nerdism) to online (and even real-world!) activism to mindful engagement on social media to the cultivation of mindfulness more generally.

Which brings us to my New Year’s resolution and my buried lede:

New Year’s resolution: I want to get more systematic about fighting this war—develop some kind of project that could make real inroads against Trumpism and tribalism and some kind of contribution to, you know, averting the apocalypse.

Buried lede: As part of that project, this newsletter will transition—as they say in the newsletter business—to a paid subscription model. We’re still working out the details, but this much I can say now:

1) The transition will happen sometime in January.

2) The paid version will come out more often than this newsletter has been coming out. That’s not a high bar, I know, so let me raise it: the paid version will come out much more often than this newsletter has been coming out.

3) The paid version will be different in form from this version—in fact, we’ll be experimenting with different forms.

4) There will still be a free version of the newsletter that includes some but not all, or even most, of the stuff that has earlier appeared in the paid version. The free version will probably come out about as often as the current version does.

The next issue of NZN will include details about this coming transition, along with some elaboration on why I consider it to be part of the larger apocalypse aversion project.

When I’m feeling optimistic, I see Trumpism as the birth pangs of a new world waiting to be born. It would be a world that, recognizing the non-zero-sum dynamics among nations and peoples, congealed into a true global community—a community cohesive enough to solve big problems but also a community in which particular national, religious, ethnic, and cultural traditions could be secure in their identities. In 2021 this newsletter will work harder to help that world be born.

To share the above piece, use this link.

What is Progressive Realism?

A couple of weeks ago the Washington Post published, in its Sunday Outlook section, a piece I wrote about the foreign policy paradigm I call “progressive realism.” In the course of the editing process, my lede was changed a bit and a few hundred words vanished—a loss I would have found less traumatic had they not included a couple of treasured bits of snark. As therapy for myself, I now present the director’s cut—the piece as it looked before cooler heads prevailed:

Recently Michael McFaul, ambassador to Russia under President Obama, expressed puzzlement about a term he had been hearing—a label adopted by some people on the left who aren’t happy with the emerging outlines of the Biden administration. “In the debate about the future Biden foreign policy I’m seeing people self-identify as ‘progressive realists’,” he tweeted.

This term bothered McFaul. After all, in foreign policy circles, “realism” has long signified a strict focus on national interest, with little regard for the welfare of people abroad. The famously pitiless Henry Kissinger called himself a realist. Maybe McFaul had Kissinger in mind when he lamented the “deaths and horrific repression” that past realists had countenanced and then asked plaintively, “Where are the progressive idealists?"

Speaking as a progressive realist, let me first say that the answer to that question is easy. “Progressive idealists” are everywhere!

If by that term you mean left-of-center people who wax idealistic about America’s global mission—who think our foreign policy should emphasize spreading democracy and defending human rights abroad—then “progressive idealists” pervade liberal foreign policy circles and will be running the show in a Biden administration. Tony Blinken and Jake Sullivan, Biden’s picks for secretary of state and national security adviser, are progressive idealists.

That’s the problem. Though McFaul considers realism an ideology with blood on its hands—and God knows Kissinger has plenty of blood on his—the fact is that in recent years naive idealism has been responsible for much death and suffering and dislocation. And a lot of that happened on the watch of the Obama administration, where Blinken and Sullivan played important roles; both did stints as Vice President Biden’s national security adviser and both had high-level state department jobs.

So, with another round of progressive idealist foreign policy apparently on the way, it’s worth reviewing the previous round and seeing how things might have been different had realists been in charge. What follows are four basic principles of progressive realism along with examples of their violation by Blinken and Sullivan and the Obama team generally. Whether or not this exercise inspires any defections from the idealist to the realist camp, I hope it will inspire people like McFaul to revisit their assumptions about the moral superiority of idealism.

1) Strategic humility. One thing contemporary realists of the left and right share is a healthy respect for the law of unintended consequences—an awareness, in particular, that the best-intentioned military interventions have a way of making things worse. One thing Jake Sullivan and Tony Blinken have in common is their support for past interventions that made things worse.

You can read the rest of this piece at nonzero.org.

Apparently nice guys don’t really finish last. In Psyche, psychologists Craig Neumann and Scott Barry Kaufman write that people with “dark” personality traits like Machiavellianism have disproportionately poor job performance and heightened risk of violent death, while those with “light” personality traits like empathy report greater happiness and self-esteem. But there’s good news for those of us with a mean streak: Neumann and Kaufman found that “light” traits can be, and often are, learned over time. “Our research, and studies of our closest relatives, nonhuman primates, both show that moral behavior can emerge and change across development—in large part through cooperative social interactions,” they write. “Thus, by embracing and trusting social connections, we can progress toward a light personality trait profile—a pathway that appears to lead to healthy self-actualization and even transcendence.”

In the New York Times, Neal K. Katyal and John Monsky look at one of Trump’s last-gasp hopes for reversing the results of the election: the possibility that Vice President Pence could on Jan. 6 abuse his role as presiding officer at the counting of the electoral votes by Congress.

In the Kausfiles newsletter, Mickey Kaus, gets alarmed by news that covid vaccine distribution may be guided by “social justice” criteria. In this scenario, “essential workers” would—because many of them are people of color—get vaccinated ahead of senior citizens, a whiter demographic. Kaus attributes this proposal to Wokism and argues that Joe Biden could and should put Wokists in their place.

In Wired, Lily Hay Newman writes about the growing frequency and success of ransomware attacks in 2020 and the chances of this trend continuing in 2021.

In the American Conservative, Blaise Malley argues that Biden’s foreign policy won’t be as far left as his domestic policies and offers a theory as to why: many Democrats reflexively oppose policies championed by Trump, and Trump’s foreign policy instincts often align with those of anti-war progressives. “Even if advocating the reverse of what Trump has done means espousing centrist, liberal interventionist or neo-conservative approaches, many opponents of the outgoing president are likely to do so,” Malley writes. “Biden can revert to a conventional form of foreign policy precisely because he can couch it as the opposite of Trump.”

A handful of reporters got famous by battling the Trump Administration. Will they maintain their combative stance after Biden enters office? In the Atlantic, McKay Coppins explores the incentive structure that shapes reporting about presidents.

Pope Francis took aim at tribalism with his recent encyclical letter “Fratelli Tutti." In Commonweal, William T. Cavanaugh reflects on the subtle radicalism of the document’s emphasis on “fraternal love,” which Francis holds up as a response to divisions sown by cynical leaders and neoliberal economic policies. The kind of love the pope has in mind, writes Cavanaugh, involves interaction and even friendship across lines of racial and economic segregation. “Pope Francis is calling us to create different kinds of spaces—economic, political, and social—where we can encounter one another face to face, where we can regard each other as children of the same God and begin the difficult journey of love.”

In Responsible Statecraft, Annelle Sheline takes a dim view of the recently announced deal that will have Morocco normalize relations with Israel in exchange for US recognition of Morocco’s annexation of Western Sahara. Sheline argues that the deal not only flouts international law but threatens global food security. Still, she doubts that Biden will roll back the decision. “Although the Biden administration may be less captured by pro-Israel interests than Trump, Anthony Blinken’s State Department will not wish to re-open the issue and risk undermining a normalization agreement with Israel.”

The New Yorker dedicates most of its latest issue to "The Plague Year," a sprawling piece by Lawrence Wright that tracks epidemiological, political, social, and personal efforts to combat covid.

OK that’s it! You can reach us at nonzero.news@gmail.com and follow us on Twitter here. (We’re tantalizingly close to the 2,500 followers mark. The rest is up to you.) Happy New Year!

Illustrations by Nikita Petrov.

Trump and Trumpism are really the inevitable consequence of all that went before, including Clintons and Obama - especially them. They have ceded ground at every turn to the right, acquiesced enthusiastically in all the wars on evil foreign brown people, to de-regulation etc. No matter how far right the Dems allow themselves to be pushed, they still cannot get enough of appeasement and compromise with this extreme rightwards drift. This is the most depressing aspect of what Biden is already doing. Instead of treating the GoP with the contempt which it deserves, and with which the GOP treats the Dems as a matter of routine, Biden is already cap-in-hand for their approval. Seriously, if anyone wants to tackle 'Trumpism', they had better start with the Democratic Party.