Logic behind Ukraine peace talks grows

Plus: China bashes Biden space proposal. Bigger BRICS is a big deal. Space junk trash bag. Deepfake detector. US chip war backfiring? Sanctions still don’t work. And more!

This week brought reports—in the Wall Street Journal, CNN, and so on—that Ukrainian troops, three months after launching their counteroffensive, have finally broken through the first of Russia’s main defensive lines. The reports aren’t untrue, strictly speaking, but they’re misleading.

Russia’s “Surovikin lines” (named after the general who designed them but then got sidelined over his ties to the mutinous and recently assassinated mercenary magnate Yevgeney Prigozhin) have three rows. The first two—a wide and deep “tank ditch” and a string of four-foot-high concrete pyramids known as “dragon’s teeth”—are meant to stop armored vehicles (or slow them down enough that they’re easy prey for artillery and drones). The third row is a line of trenches and bunkers manned by Russian soldiers.

There’s no evidence that Ukrainian armored vehicles have gotten past any of these rows. But infantrymen have crossed the first two rows and taken over at least one segment of the manned trenches. That’s impressive—especially given all the mines laid between rows—and it’s a significant milestone. But it doesn’t create what words like “breakthrough” and “breach” connote: a gap in the defensive line through which tanks and other armored vehicles can pour.

And, anyway, in an environment where armored vehicles get destroyed mainly by drones and artillery, it’s not clear that even a true breach of terrestrial defenses would allow a river of armor to flow very far very fast.

In sum: the Ukrainian counter-offensive is roughly what it was a month ago—a long, hard slog, featuring incremental gains, incremental setbacks, and lots of casualties. The counteroffensive’s goal of “severing the Crimean land bridge” is nowhere in sight, and the dream of evicting Russian troops from all of Ukraine remains a dream.

But there’s good news of a sort. It lies in an assessment of Russian politics published this week by one of the West’s most sober analysts of Russian and Ukrainian affairs, Anatol Lieven of the Quincy Institute. Lieven’s analysis suggests that Russia may be ready to talk peace. In which case the main obstacle to peace talks is convincing Ukraine’s leaders that an imperfect peace is the best they can hope for—a proposition that the counteroffensive’s meager results and huge human and material costs should lead them to seriously entertain.

Lieven writes in the Guardian:

From conversations I’ve had, it appears that a large majority of elite and ordinary Russians would accept a ceasefire along the present battle lines and would not mount any challenge if Putin proposed or agreed to such a ceasefire and presented it as a sufficient Russian victory.

Hardline nationalist elements in the establishment and military would be deeply unhappy; but they have been weakened by Prigozhin’s fall and the accompanying steps that Putin has taken to curb their influence, including the dismissal of two generals and the arrest of the ultra-nationalist leader and former Donbas militia commander Igor Girkin.

Lieven emphasizes that, though most Russian elites didn’t favor the invasion and don’t share the nationalists’ yearning for total victory, “there is still a general unwillingness to see Russia defeated and humiliated in Ukraine… Nobody with whom I have spoken within the Moscow elite, and very few indeed in the wider population, has said that Russia should surrender Crimea and the eastern Donbas.”

In short: Though Putin continues to resist the big military mobilization it would take to make the nationalists’ dreams of conquest realistic, he would probably have grassroots and elite support for a mobilization if that’s what it took to keep a future Ukrainian offensive from succeeding on a large scale.

All of which underscores something the results of this summer’s counteroffensive also underscore: Ukraine is fighting a war of attrition against a country that has more than three times as many fighting-age males as it has.

It would be nice if the neoconservatives and liberal interventionists who dominate the US foreign policy establishment and dismiss the idea of peace talks acknowledged that this is the war they favor sustaining. And, since they tend to cast themselves as champions of the Ukrainian people, they could stand to ponder one implication of sustaining such a war: Though the number of Ukrainian men who have lost arms and legs and lives is by now into six figures, the worst may be yet to come.

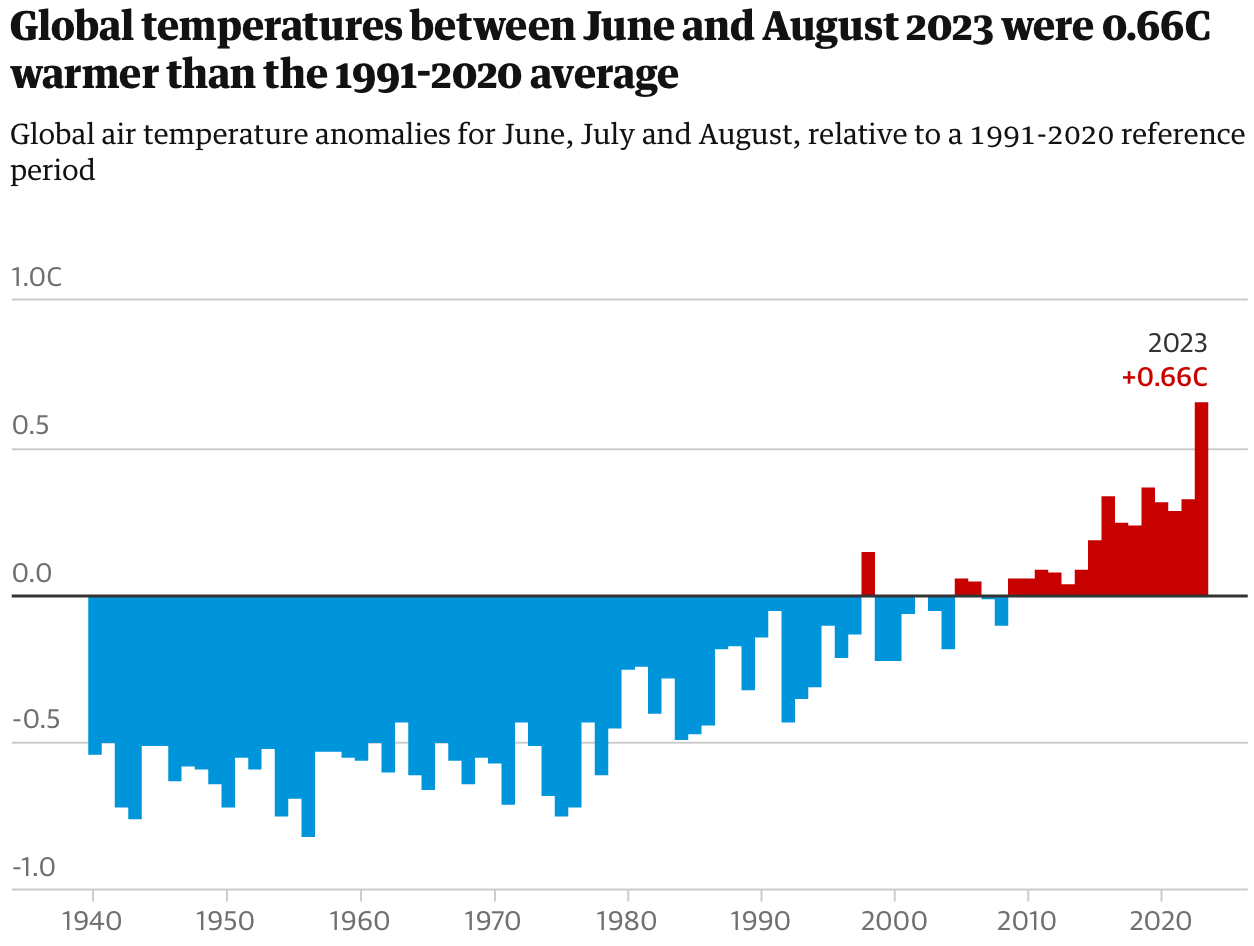

Summer 2023 was the hottest on record, according to data from the EU. From June through August, average global temperatures hit 62.19 degrees Fahrenheit, breaking the previous high (set in 2019) by 0.52 degrees. Climate scientists blame not just carbon emissions but also this year’s appearance of El Niño.

If you’re hoping the carbon-absorbing power of trees will make a big dent in global warming, here’s some cold water: In the New York Times, recent Nonzero podcast guest David Wallace-Wells explains why we should be skeptical of arboreal-based apocalypse aversion strategies. You can watch David discuss the finer points of carbon capture—and other climate hot-topics—on the NZN YouTube channel here.

With AI-generated images—including “deepfakes”—proliferating, it would be nice to have an easy way to detect them. Last week, Google's DeepMind division introduced a digital watermark technology called SynthID to help do that. The labels are invisible and designed to be detectable even after cropping or other modification.

While the technology currently works only with Google Cloud's own text-to-image generator, Imagen, the hope is that if enough big names in the industry adopt such standards, the rest will follow. Alternatively, governments could mandate watermarks—though, like so many AI regulations, this one would need to be international to be very effective.

Will the Biden administration’s chip war against China work? This week Huawei released a smartphone that is being taken by some as an answer. That answer is: