Michael McFaul, useful Ukraine weathervane?

Plus: Creepy AI teddy bears, climate doom anti-baby boom, China-Cuba axis: made in USA, paid subscriber perks, and more!

There are signs that, nearly three weeks into Ukraine’s much-heralded counteroffensive, things aren’t going well. There is President Zelensky’s admission that progress is “slower than desired,” there is a western official’s judgment that the offensive is “not meeting expectations on any front,” and, perhaps most tellingly, there is this: Michael McFaul, the extremely hawkish former US ambassador to Moscow, is suddenly talking about preparing the ground for peace talks. In a Washington Post op-ed, he’s come out of in favor of a “diplomatic surge.”

McFaul’s traditional position on diplomacy in Ukraine has been that people who propose it are hopelessly naive. “To those claiming to make the ‘case for diplomacy,’” he tweeted last year, “please detail how you would persuade or compel Putin to stop the conflict.”

Well, the logical reply to that remains true today: We won’t know whether Putin is open to serious diplomacy until we pursue it (and until President Zelensky drops his refusal to negotiate so long as Russia occupies even a square inch of Ukrainian territory). But one thing seems sure: Putin will be less inclined to negotiate after a failed offensive that leaves the Ukrainian army decimated than he would have been before the offensive started, when for all he knew it would be a smashing success. It may turn out that Michael McFaul showed up to the diplomacy party later than was optimal.

Some of us advocated diplomacy back in December, in the wake of two big Ukrainian battlefield successes, and suggested that Ukraine wasn’t likely to gain much ground at acceptable human cost thereafter. (Ukraine has on balance lost ground since then, along with many thousands of lives.) Some of us also, two months ago, advocated canceling the offensive and using the tens of thousands of troops freshly trained and equipped for it to render Ukraine’s defensive line essentially impenetrable.

One goal of such a move would be this: Convince Putin that he might as well talk peace, since his best case scenario is something like a stalemate, along with ongoing attrition (that is, ongoing death for Russian soldiers, with no compensating gains to show the Russian people).

Though the opportunity to adopt this “assertive defense” has diminished over the past three weeks, it hasn’t disappeared. Thousands of Ukrainian soldiers have been killed or wounded in this offensive, and much armor lost, but most of the forces that were marshaled for it are intact and can still be used to anchor a newly formidable defensive line. And, though Putin is surely feeling more confident than he was three weeks ago, his confidence may not have reached diplomacy-killing levels.

Yet. But it’s probably moving in that direction. It has no doubt occurred to him that, if present battlefield trends persist for months, and Ukraine continues to lose soldiers and armor at a high rate, it will be conceivable that he could (perhaps after another round of mobilization) take all of Ukraine east of the Dnipro River, retake Kherson, and maybe even take Odessa—leaving Ukraine without a port.

If President Zelensky pursues peace he will face internal opposition, especially from the small but politically powerful ultra-nationalist element in the military. But the US, in holding the keys to Ukraine’s future arsenal, has enough leverage to provide Zelensky with the political cover he needs.

Of course, this scenario assumes that President Biden and Secretary of State Blinken will show not only wisdom but more in the way of agency than they’ve so far evinced. And it assumes that Biden will get the political cover he needs (or at least thinks he needs) to play peacemaker.

In theory, much of that cover would come from the Michael McFauls of the world—the hawks who constitute most of the US foreign policy establishment and whose seal of approval is deemed important, notwithstanding their longstanding tendency to be wrong about things (disastrous Iraq ground invasion, disastrous Libya aerial intervention, disastrous Syria proxy intervention, etc.).

Is McFaul’s newfound enthusiasm for diplomacy auspicious, then? Not necessarily. On close inspection, his call to “appoint a special envoy for peace talks” between Moscow and Kyiv seems to be cosmetically motivated. He notes that China has appointed such an envoy, so “we’re being outplayed by the Chinese.” He says our envoy should “shadow” China’s envoy, Li Hui, and counter Li’s pro-Russia talking points with anti-Russia talking points. And one of our talking points should be that more sanctions on Russia are in order.

Maybe the good news is that McFaul now feels the need to package his hawkishness in the guise of dovishness. You don’t rise to the Blob’s upper echelons and amass a Twitter following of 800,000 without knowing which way the wind is blowing.

Attention NZN members! This week we bring you two paid subscriber perks:

Early Access to Bob’s conversation with foreign policy expert Sean Mirski, author of the upcoming book We May Dominate the World: Ambition, Anxiety, and the Rise of the American Colossus. Bob and Sean discussed China, Russia, Latin America, and how the US got its interventionist habits. To watch or listen to the episode, click here, or look for it in your paid-subscriber podcast feed.

The latest edition of the Parrot Room, Bob’s after-hours conversation with arch-frenemy Mickey Kaus.

Could fears of climate change lead to fewer baby Earthlings?

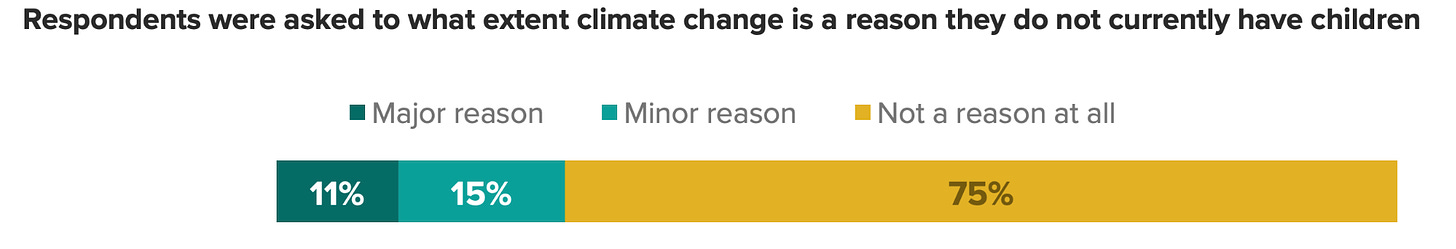

Fifty three per cent of parents surveyed on three continents say climate change has “impacted their perspective on having more children.” The survey, conducted by Morning Consult and commissioned by the tech company HP, involved 5,000 parents in India, Mexico, Singapore, the US, and the UK. A 2020 Morning Consult survey found that 1 in 4 childless Americans cite climate change as one reason they don’t have children.

A question for those one in four: If you’re concerned about global issues like climate change, isn’t it pretty likely that you could convey that concern to your children? By extension, if all the people concerned about climate change decided to forego childbearing, mightn’t that reduce the next generation’s inclination to address it and other such issues?

Plus: Life has always been hard—in many eras harder for the average human than it is now. But as a rule it beats the alternative.

The Wall Street Journal reported this week that “China and Cuba are negotiating to establish a new joint military training facility on the island.” And this comes on the heels of a Journal report 12 days earlier that the two countries “have reached a secret agreement for China to establish an electronic eavesdropping facility on the island, in a brash new geopolitical challenge by Beijing to the US.”

The foreign policy establishment tends to take developments like these as vindication of President Biden’s conception of America’s great calling: to lead the world’s democracies in a global struggle against an insidious network of autocratic (and authoritarian) states. But you could also see these developments as roughly the opposite: evidence that Biden’s foreign policy vision is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

What motivates Cuba to lock arms with China? There’s a clue in the first of those two Journal articles: