Michael McFaul’s dangerous muddle

Plus: How AI could kill the internet, one weird trick to promote human rights in Cuba, deforestation ramps up, and lab-grown chicken nuggets are here! Plus: NZN member benefits.

The dust hasn’t settled in the wake of Yevgeny Prigozhin’s failed Russian mutiny, but Michael McFaul can already discern the moral of the story. McFaul, the former US ambassador to Moscow who is now an influential Russia hawk, says Putin’s handling of the crisis shows that fears of his using a nuclear weapon are exaggerated; Putin chose to negotiate with Prigozhin rather than fight, so we can assume that he wouldn’t go nuclear if faced with big losses on the battlefield, including even the loss of Crimea.

“The lesson for the war in Ukraine is clear,” McFaul tweeted. “Putin is more likely to negotiate and end his war if he is losing on the battlefield. Those who have argued that Ukraine must not attack Crimea for fear of triggering escalation must now reevaluate that hypothesis.”

It’s important to understand how confused McFaul’s guidance on this issue is. The roots of the confusion seem to lie in his comic-book caricature of the position he’s arguing against. McFaul writes of Putin and his handling of the mutiny: “He was the rat trapped in the corner that so many Putinologists have told us to fear. But he didn't lash out and go crazy. He negotiated.”

It’s true that Putin didn’t go crazy. But that’s irrelevant to the main argument being made by those of us who worry that he might escalate under pressure by using a tactical nuclear weapon. Here’s that argument:

(1) Battlefield setbacks could reach a point where Putin fears for the survival of his regime. The closer Ukrainian troops move to Russia’s pre-2022 borders, the more inclined Russians will be to deem his invasion a blunder and/or his conduct of the war incompetent, so the more likely a coup (or, conceivably, a popular uprising) will be.

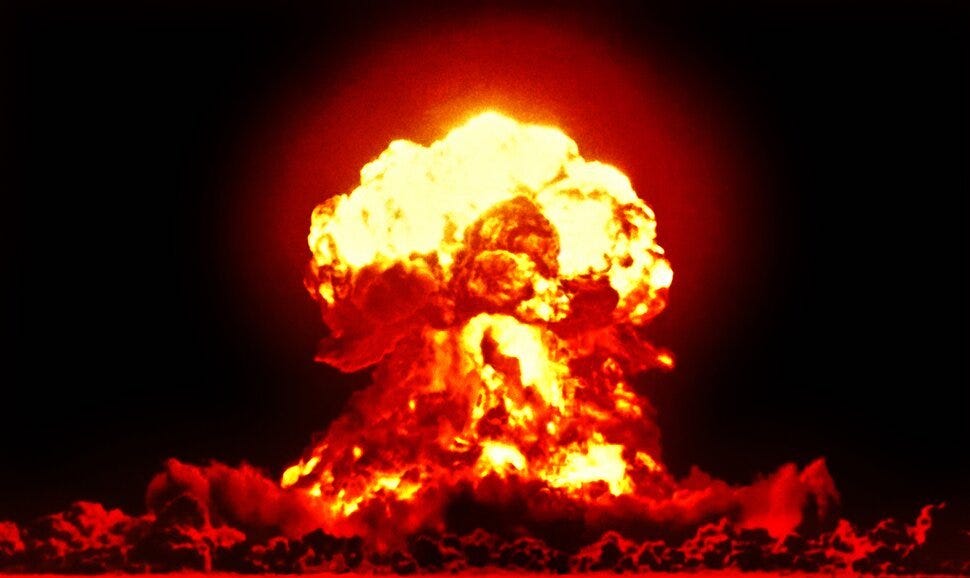

(2) Putin, bent on ensuring the survival of his regime, would then consider it imperative to stop the progress of Ukrainian troops. He might calculate that a nuclear strike—for “demonstration” purposes—would get the Ukrainian government and its western backers to stop and reconsider the wisdom of further advances.

Such a move may strike you as a bad bet, but the thing about existential threats is that they lead people to make bad bets—not because these people are “crazy” but because they’re so determined to avoid a loss they consider unacceptable that they’ll make what they see as the best bet available, even if it’s not a great one.

And note that in this case the existential threat has two dimensions. First, there’s a threat to the existence of Putin’s regime. Second, the closer Ukrainian troops come to Russian territory, the more they—along with the NATO countries that are arming them—can be cast as an existential threat to Russia itself.

Russia’s nuclear doctrine authorizes the use of nukes in the case of that second kind of existential threat. What’s more, Russian strategists take seriously the idea of “escalating to de-escalate”—the idea that a nuclear strike could succeed in halting an enemy in its tracks rather than lead the enemy to retaliate in kind or in comparable magnitude.

If you’d like to see an influential Russian seriously ponder the near-term use of nuclear weapons, you’re in luck. Earlier this month, political scientist Sergei Karaganov—who has advised both Putin and, earlier, President Boris Yeltsin—published an essay called “A Difficult but Necessary Decision.” Karaganov argues that Moscow should lower the threshold for the use of nukes in the Ukraine war. And if a preemptive nuclear strike against Ukraine—or against one of its European supporters—doesn’t make the West back off, “we will have to hit a bunch of targets in a number of countries in order to bring those who have lost their mind to reason.”

McFaul, along with many other observers, says Prigozhin’s attempted mutiny has left Putin’s regime weaker than before—and has also exposed pre-existing and underappreciated weakness. He may well be right. Indeed, Putin himself seems to share this view, judging by how hard he’s working to convey authority and calm while his administration works furiously to identify Prigozhin sympathizers. But note one implication of Putin’s awareness of his weakness: It means he is now more likely to respond to severe battlefield losses by escalating than he would have been only two weeks ago—because he has more cause to worry about his regime’s survival.

At least, that’s the implication if you buy the main argument being made by those of us who worry that Putin might escalate. Maybe McFaul can come up with reasons to reject this implication. But to reject it he’d have to first grasp it, which in turn would require him to grasp the argument itself—a challenge that so far he hasn’t met.

So let’s try to boil this down for him: Our concern is that Putin will escalate in the course of rationally (as he sees it) trying to preserve his regime.

Notably, one way to describe how Putin handled the Prigozhin mutiny is to say that he rationally tried to preserve his regime—and succeeded. For a few hours last Saturday success seemed far from assured. A coup seemed possible, and a civil war seemed possible. Neither of those things happened. Putin once again showed himself to be, above all, a survivor.

Yet McFaul seems to expect Putin, if cornered, to gracefully surrender—because, according to McFaul, that’s what happened last week. He says Putin “capitulated” to Prigozhin.

Huh? Prigozhin had these demands: (1) Don’t integrate Wagner’s forces in Ukraine into the Russian military. (2) Fire Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu. (3) Fire Chief of the General Staff Valery Gerasimov. Prigozhin got none of these things. Plus, he got exiled! And the (probably few) Wagner troops who choose to follow him into exile won’t be allowed to bring heavy armaments.

Putin did make one big concession: he abandoned his threat to charge Prigozhin with treason. If McFaul wants to argue that Putin could have cut a better deal—that he could have gotten out of this mess without giving Prigozhin a reprieve yet without large-scale and ultimately destabilizing bloodshed—then he should make that argument. (Good luck.) But for a former ambassador to characterize the deal Putin cut as “capitulation” is to demonstrate a puzzling unfamiliarity with the vocabulary of international relations. And for the US to expect Putin to capitulate down the road is to court disaster.

Attention paid subscribers! This week we bring you three NZN member benefits:

1. The latest edition of Earthling Unplugged, Bob’s conversation with NZN staffer Andrew Day about items from The Earthling, along with a few stray thoughts.

2. Early access to Bob’s conversation with Google AI researcher (and mathematical physicist) Timothy Nguyen. Tim does his best to explain to Bob how large language models work, and Bob does his best to get the picture. Plus, near the end, Tim gives us an update on well-known self-described genius Eric Weinstein. (The previous Bob-Tim conversation was titled “Is Eric Weinstein a Crackpot?”)

3. Tonight’s edition of the Parrot Room, the after-hours conversation between Bob and Mickey Kaus that directly follows their weekly public podcast.

And remember: If you’re a paid subscriber and you set up your special members-only podcast feed, this kind of bonus content will flow automatically into your podcast app forevermore, alongside the publicly available content. To do that, click the links in items 1 or 2 above and then click “listen on.”

US sanctions against Cuba for human rights abuses show no signs of having their desired effect (unless their desired effect is to make innocent Cubans suffer). But here’s something that might improve the human rights situation in that country: