When the New York Times warps our view of the world

Plus: The Trumpiest day in months; Virality and Virulence; Verizon, Facebook, and other menaces...

Welcome to another NZN! In this issue I (1) revisit one of the most intensely Trumpish days in the history of Trumpism; (2) accuse the New York Times of consequentially warping our view of Syria; (3) recount my roller coaster ride, on Friday, through the dark depths of Twitter infamy into the glorious sunshine of Twitter affirmation; (4) steer you to background readings on such things as curiosity and its hijacking, negative partisanship and its perils, creeping facial recognition technology and its creepiness, and Verizon’s plan to erase a non-trivial chunk of the collective human memory.

But first: Thanks to the new NZN subscribers—and for that matter the old NZN subscribers—who this week helped push our subscription past the 14,000 mark. (Social media bragging here.) Next stop: Total domination of the noosphere.

Essence of Trump

Thursday was an amazing day even by the elevated standards of the Trump era. In the span of a few hours, these four things happened:

1) The Trump administration said it had orchestrated a five-day ceasefire—whose wording, it turns out, validated Turkey’s invasion of Syria the week before and its goal of creating a 5,400-square-mile “buffer zone” in the Kurdish part of Syria.

2) In proudly discussing the ceasefire, Trump seemed to validate, as well, one product of that invasion: the ethnic cleansing of some 150,000 Kurds over the past two weeks. Trump said that, from Turkey’s point of view, northern Syria had to be “cleaned out,” and that sometimes you need to exercise “a little rough love,” an “unconventional, tough love approach.” Which in this case apparently entailed invading a country in plain violation of international law, shelling and bombing it, and, for good measure, deploying Syrian jihadists who set about committing atrocities that terrified Syrian Kurds into fleeing—all of which left Kurdish troops little alternative to accepting the ceasefire. Or, as Trump cheerfully characterized the dynamic he’d set in motion by abruptly withdrawing US troops from northern Syria: “When those guns start shooting, they tend to do things.”

3) The White House announced that next year’s G-7 summit will be held at Trump’s Doral golf resort. This would seem to violate the Constitution’s Emoluments clause, which prohibits the president from accepting “any present, Emolument [profit or benefit], Office, or Title” from a foreign government. Even if you accept Trump’s claim that Doral will give everyone such a deep discount that he won’t make a profit (warning: don’t accept that claim!) there is huge “branding value” in hosting the G-7 summit—both the publicity emanating from the event and the longer-term value of the resort becoming historically significant. (No doubt Trump is already imagining Doral’s walls adorned with commemorative plaques and pictures of him and his fellow potentates.) But I guess if you’re getting impeached anyway you might as well go whole hog. And speaking of impeachment:

4) Trump’s chief of staff, Mick Mulvaney, openly admitted that Trump withheld military aid from Ukraine to pressure it into seeking information that would help him politically—specifically, evidence that would support his claim that Russia hadn’t actually hacked the DNC’s email in 2016. This admission doesn’t add as much fuel to the impeachment bonfire as would have been added had Mulvaney said that investigating Hunter Biden was another goal of the arm twisting. But it added enough fuel that Mulvaney, after a brief period of reflection and consultation, said he hadn’t actually said what he’d said.

As a rule, this newsletter ignores the white noise of Trump’s ongoing ethically and legally dubious behavior. After all, the premise behind the newsletter’s predecessor, The Mindful Resistance Newsletter, was that mounting serious opposition to Trumpism requires discipline—not being distracted by Trump’s daily antics and transgressions, not reacting to them in ways that play into his hands, and not letting a perfectly understandable loathing of him warp our view of the world. In fact, this newsletter, like its predecessor, spends at least as much time criticizing people who abet that warping (see, for example, my criticism of the New York Times immediately below) as criticizing Trump.

Still, every once in a while you have to pause and take stock—reflect on how high the stakes are and, lest Trump’s biggest transgressions be normalized, note what big transgressions they are. Any one of the four things listed above would, in ordinary times, dominate the news for many days. And rightly so. So let’s do pause briefly and reflect on Thursday, October 17, 2019—the 1001st day of Trump’s presidency—before getting back to the war on Trumpism.

How the New York Times distorts our view of Syria

The New York Times wants to make sure you know that Trump’s withdrawal of US troops from northern Syria has strengthened US adversaries.

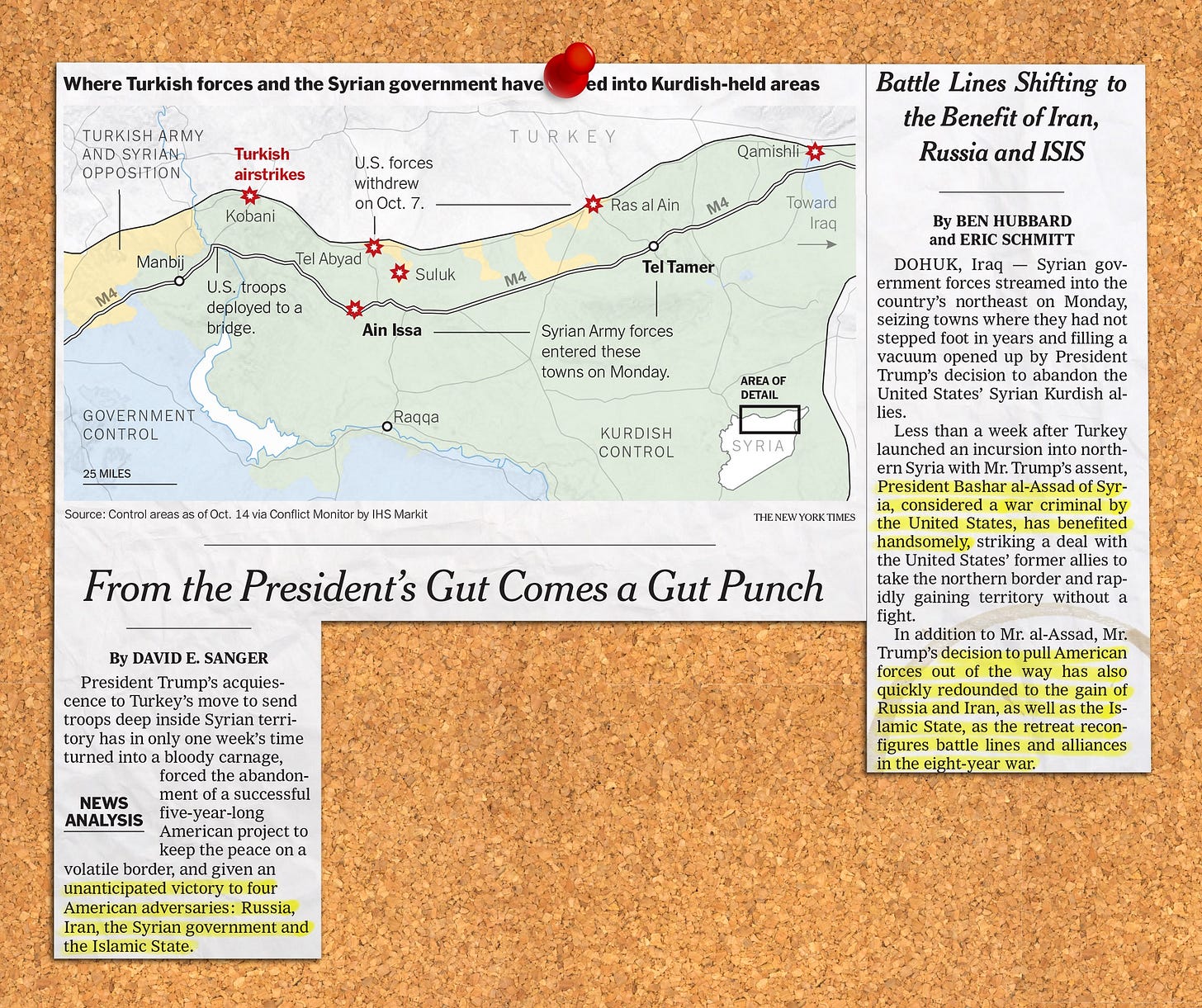

On Tuesday, after Kurds imperiled by the withdrawal cut a deal with the Syrian government to step in and protect them—thus expanding the influence of the Syrian regime and its allies, Iran and Russia—the Times featured two front page stories about Syria. Over one of them was a headline that said “Battle Lines Shifting to the Benefit of Iran, Russia and ISIS.” The other one said, in its very first paragraph, that Trump had “given an unanticipated victory to four American adversaries: Russia, Iran, the Syrian government, and the Islamic State.”

OK, we get the message. But there’s a problem with the message. These two stories are at best misleading and at worst flat-out wrong. And, sadly, they’re typical of much mainstream media coverage of Syria—and reflective, I think, of cognitive distortions that afflict many American journalists, warping our view of the world.

The first warning sign, in both of these stories, is a paradox: some of the parties they call beneficiaries of recent developments—Syria, Iran, Russia—are enemies of another party they call a beneficiary of recent developments: The Islamic State, or ISIS.

Now, it’s not impossible that a deal that strengthens Syria and its allies could also help their enemy. On the other hand, the Syrian regime considers ISIS a very threatening enemy, and can be counted on to try to destroy any remnants of ISIS within reach. And when these two stories appeared, that reach had just been greatly expanded, via the deal that the Kurds had cut with the Syrian regime. So isn’t it possible that the deal would actually hurt ISIS rather than help it?

I want to be clear: Trump’s original withdrawal of American troops had presumably helped ISIS by directing the attention of the Kurds away from ISIS and toward the Turkish incursion. I noted this effect in last week’s newsletter (qualifying it with “at least in the short run”).

But now we were seeing an influx of Syrian and Russian troops into Kurdish territory, and that could direct fresh and hostile attention toward ISIS. So, all told, this influx was cause to think that the previous week’s concerns about a resurgent ISIS (which the Times had spent plenty of ink on) may have been overblown. Indeed, was it even conceivable that the long-run consequences of Trump’s troop withdrawal could turn out to be, on balance, bad for ISIS?

To check this speculation, I emailed Paul Pillar, who from 2000 to 2005 was National Intelligence Officer for the Near East and South Asia, which means he was in charge of the analysis of those regions for the CIA and all other American intelligence agencies. I asked whether it was crazy to think that Trump’s withdrawal of US troops could wind up being a “net negative for ISIS”—since, as I put it, there would now be an overall increase in “the number of armed enemies of ISIS” in Kurdish territory.

Pillar replied that he wouldn’t jump to the “net negative for ISIS” conclusion just on the basis of the number of anti-ISIS troops in the area. He wrote, “Rather, the basic point is that those other players [Syria and its allies] have at least as much of a direct interest in combating ISIS as the United States does.” But then he added, “The one possible way you might get a ‘net negative’ out of it is that having the U.S. military on the ground as a foreign presence has been—as earlier events in Iraq and Saudi Arabia have demonstrated—a recruiting asset for radical Sunni terrorists.”

In short: the situation is complex—complex enough that the New York Times’s casual assertions about the impact on ISIS (which were basically just unreflectively recycled assertions from the previous week, when they’d made more sense) weren’t really up to New York Times standards.

And, anyway, leaving aside the question of the net impact on ISIS of Trump’s troop withdrawal, one thing is hard to deny: if you compare ISIS’s prospects the day before the Kurds OK’d the influx of Syrian and Russian troops to ISIS’s prospects the day after, they had gotten dimmer. Mightn’t the Times have at least mentioned this fact—since, after all, this influx was precisely the big development that was being reported and assessed in that day’s paper?

No such luck. Neither of these two front page stories acknowledged that expanded Syrian influence should be expected to undo at least some of the damage done to the war on ISIS by the American troop withdrawal announced the previous week. Both stories (one by David Sanger and one by Ben Hubbard and Eric Schmitt) kept their preferred narratives—that the wind was in ISIS’s sails—unsullied by fresh analysis.

I don’t think any of these reporters are trying to deceive us. I suspect they’re victims of two cognitive distortions, and are inadvertently inflicting those distortions on us.

1) Crudely zero-sum thinking. There definitely are dimensions along which the US has a zero-sum relationship with Russia, with Syria, with Iran. But the trouble with the label “adversaries” (or, worse still, “enemies”) is that it suggests a zero-sum relationship along all dimensions. It keeps you from even entertaining the possibility that something that’s good for Russia, Syria, or Iran could be good for the US. But it could be. In the real world—whether we’re talking about a person’s relations with “friends” and “enemies” or a nation’s relationship with them—there are very few purely zero-sum or purely non-zero-sum relationships.

2) #Resistance thinking. The New York Times, the Washington Post, and other media outlets are working in a polarized political environment, which means they can best prosper by catering to one political tribe or the other. And they’re working in a technological environment that provides precise and instantaneous information about how many readers each of their stories gets—a fact that puts individual reporters and editors who want a big readership (and don’t all of us want a big readership?) directly in touch with this tribalizing incentive. Plus, of course, a lot of journalists have feelings about Trump that are strong enough to color their thinking without them realizing that.

All told, media sites tend to move toward one of two camps—Trump or the Resistance. I don’t think the New York Times is as much in the Resistance camp as, say, Fox News is in the Trump camp. But I think it leans in that direction, even if that’s not the conscious intention of its reporters and editors. Possible bad consequences of Trump policies come more readily to mind than possible good consequences.

My speculations about the Times’s institutional psychology aside, there’s no doubt that a Times story saying Trump has delivered a victory to our enemies, like a Fox News story saying he has vanquished our enemies, will draw a bigger audience than a story saying the truth is more complicated than either of those narratives. Yet complicated is what the truth often is. And I think our foreign policy would be less destructive than it’s been in recent years if our most important media outlets did a better job of conveying the complexity.

Virality and virulence

This week I was reminded anew of the promise and peril of tweeting right after your morning coffee. And in the process I was reminded (not that I really needed it) of Twitter’s tribal nature.

On Friday morning, just as the caffeine was taking full effect, and I was settling in to work on this newsletter, I fatefully took a look at my Twitter feed. I saw that Hillary Clinton, in an interview, had suggested that Tulsi Gabbard was being “groomed” by Russia to be a third-party spoiler candidate, and that Jill Stein, who played that role last time around, was “also” (like Gabbard, that is) a “Russian asset.”

That’s pretty extreme. As Hillary Clinton undoubtedly knows, and as Wikipedia confirms, the term “asset,” in that context, is typically taken to mean that the person in question isn’t just being exploited by a foreign power but is consciously and secretly cooperating. Not to mention the fact that people aren’t typically “groomed” without being aware of it.

Now, my opinion of Jill Stein—like my opinion of Ralph Nader ever since his third party candidacy got George W. Bush elected president—is low. And I’m not a big Gabbard supporter. I like much of what she says about foreign policy, but I also find her in some ways offputtingly quirky. (For example: She replied to Hillary’s conspiracy theory with a kind of conspiracy theory of her own. And, though I’d like to think this was sly commentary on Hillary’s seeming paranoia, I fear it wasn’t—and if it was, I think it was too subtle for its own good.)

But, all that said, there are few things that trigger me more than McCarthyism, and Hillary’s accusations struck me as a clear case of it. So, with what in retrospect seems like remarkably little reflection, I tweeted: “Hillary now has two respectable options: either provide evidence to back this up or apologize to Stein and Gabbard. Anything else is an indictment of her character.”

That last line was the coffee talking. I mean, I stand by it, kind of, but it’s a little on the Olympian side. Come to think of it, so was the first line.

Anyway, I quickly saw that I was being “ratioed”—that is, the ratio of replies to retweets and likes was pretty high, which is often a sign of negative reaction. Further exploration confirmed the negativity.

I did enough interacting with my critics to discern that by and large they either (1) thought that Jill Stein’s having sat at a dinner table with Vladimir Putin, or Tulsi Gabbard’s having met with Bashar al-Assad (whom she also called a “brutal dictator,” by the way), were conclusive evidence of conspiracy; or (2) insisted that Hillary wasn’t suggesting conspiracy—the former Secretary of State, apparently, was using the term “Russian asset” in a way it’s not typically used in the State Department.

It’s amazing how unpleasant widespread criticism can be even when you’re convinced that the critics are confused. This was a kind of suffering that even caffeine couldn’t overcome.

My coalescing regret over having tweeted was about to morph into sustained self-reproach when…the cavalry arrived! A low but persistent level of retweeting had, via the magic of Twitter’s secret algorithm, moved my tweet into a friendlier part of the opinion ecosystem. By the end of the day I had more than 500 retweets and more than 2,000 likes—a lot by my standards—and hundreds of replies, most of them supportive.

Which, I admit, cheered me up. But here’s what was depressing: To judge by the replies, at least, pretty much nobody—my critics or my supporters—was motivated by opposition to McCarthyism per se. They were either Gabbard haters or Stein haters or Hillary lovers, on the one hand, or, on the other hand, Gabbard lovers or Stein lovers or Hillary haters. For example: at least 100 of the 300+ replies consisted of people picking up on my phrase “indictment of her character” and deploying some variation on the theme that Hillary has no character. And a few people said other unflattering things about her (occasionally in ways that appealed to my sophomoric sense of humor).

But the main point is that almost every reply, whether from critics or supporters, involved a negative characterization—and usually not a very high-minded one—of one of the three players: Hillary, Gabbard, or Stein. It was an example of a phenomenon that is said to have grown greatly in the US in recent years: “negative partisanship”—tribal solidarity motivated largely by hatred of the other tribe. And the fact that in this case the word “partisanship” is misleading—that the tribal divide didn’t correspond exactly to the Democrat-Republican divide—isn’t much consolation.

In the New York Times, psychologist Daniel Willingham dissects curiosity, explains why it so often hijacked by the internet to ignoble ends, and offers some tips for fighting the hijackers.

In Fast Company, Harry McCracken asks whether Verizon, the current owner of Yahoo, is acting responsibly in deleting the archives of Yahoo Groups, a once-thriving ecosystem of online communities. “Verizon is eradicating a meaningful chunk of the internet’s collective memory,” McCracken writes. “The Yahoo Groups archive is an irreplaceable record of what people cared about in its heyday.” This won’t be the first Yahoo-related digicide. As Jordan Pearson notes in Vice, “In 2009, Yahoo shut down GeoCities, taking roughly 7 million personal websites with it.”

Two years ago in Politico Magazine, social scientists Alan Abramowitz and Steven Webster explained what “negative partisanship” (see “Virality and virulence,” above) is and why its growth is bad for American politics.

In Politico, Aaron David Miller, Eugene Rumer, and Richard Sokolsky lay out “what Trump gets right about Syria.” Among their points: “the foreign policy establishment—the ‘blob’—has spilled a lot more ink complaining that his move benefits Russia than thinking about its actual effect on U.S. interests.” Two points about this point: (1) It meshes with my complaint about New York Times coverage of Syria, above; (2) It uses the semi-derisive term ‘blob’ for the foreign policy establishment—even though these authors, especially Miller, would traditionally have been thought of as members of that establishment. This is a welcome sign that the spirit of anti-blobism may be spreading from fringe renegades (me, for example, or Stephen Wertheim and Trita Parsi of the new and edgy Quincy Institute, who have a very worthwhile piece about Trump’s Syria policy in Foreign Policy this week) into parts of the mainstream. Hey Richard Haass, the phone call is coming from inside the house!

In a week when a New York Times op-ed advocated banning facial recognition technology “in both public and private sectors,” Wired reports on the growing if still quite limited use of the technology in schools.

This week a retired admiral—and former commander of US Special Operations—won much applause by saying in a New York Times op-ed that Trump is a threat to the Republic and suggesting that this view is shared by many of the admiral’s peers. I’m ambivalent about this. I feel a bit uncomfortable when a former flag officer who implies that he speaks for many in the military writes that “it is time for a new person in the Oval Office” and “the sooner the better.” I realize he’s thinking about impeachment, not a coup, but I guess I’m old school; my father was a career army officer, and back in his day he and many other officers felt so strongly about the importance of separating the military from politics that they didn’t even vote. I have no doubt that that the admiral, William McRaven, is genuinely worried about the Republic. Me too. But but one thing about the Republic that worries me is that we’ve gotten to a point where we’re desperately looking to the military for political guidance.

Anti-trust tweet of the week: On Thursday Mark Zuckerberg, in a speech at Georgetown, declared that it isn’t Facebook’s role to play speech police. As he put it in an interview, “I don’t think people want to live in a world where you can only say things that tech companies decide are 100 percent true.” In response to which Gabriel Snyder, former editor of The New Republic, tweeted that what people don’t want is “to live in a world where just *ONE* tech company decides what people can say.”

Incoming: Thanks to all the readers who emailed us (nonzero@substack.com) in response to last week’s newsletter. Several, responding to my lamentation about the dearth of anti-war activism among Buddhists and for that matter among progressives, directed me to welcome exceptions. Two readers—Jeff A. and Dat D.—mentioned the venerable Quaker group Friends Committee on National Legislation. Alan R. of Santa Cruz, an ordained Zen priest, hailed his local chapter of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship. And Elizabeth F. provided a master list of pro-peace groups. (You have to scroll down to get to the Peace/Anti-War section, and if you’re not disciplined you may be diverted to some other kind of activism before you get there. Be strong!)

And finally: Feel free to make use of the “like” and “share” buttons below. And to follow us on Twitter. See you next week!