The neoliberal case for Bernie

Plus: A talk with Freeman Dyson; Coronavirus backlash; lovingkindness the easy way; etc.

Welcome to another NZN! In this issue I (1) argue that Bernie Sanders could be the salvation of the very neoliberal order that deems him an existential threat; (2) share a conversation I had two decades ago with the legendarily offbeat physicist Freeman Dyson, who died a week ago; (3) share links to readings on such things as: how the coronavirus could fuel nationalism and nativism; people who love doomed products; how to do lovingkindness meditation even if you’re not the type; a fraying Afghanistan peace deal; a dubiously justified Bolivian coup; and a look at the first presidential campaign ever conducted on the web.

Note: In the previous issue I said publication of the newsletter was about to become irregular (though not necessarily less frequent). As you may have noticed, that hasn’t happened. Rather, we skipped a week (which we always do after publishing three issues in a month), and now this issue is coming out on Saturday, as usual. But I still aspire to irregularity and promise to achieve it before long! Meanwhile, this week’s appeal for your promotional help: If you retweet this tweet, you’ll help spread awareness of the newsletter and earn our undying gratitude.

Why neoliberals should love Bernie

Three months ago, on the website Counterpunch, Richard Ward wrote that Bernie Sanders is “the one possible challenger to the neoliberal order.” That status, he went on to assert, accounted for the timing of the Senate impeachment trial; it was the neoliberal order’s way of keeping Sanders off the campaign trail. I can only imagine what Ward thought this week after the Democratic establishment swung into action to convert Joe Biden’s victory in South Carolina into victory on Super Tuesday.

If Biden’s resurrection was indeed in some sense the work of the “neoliberal order,” the effort may have been misguided. However qualified Sanders is to overthrow that order, he’s also qualified—maybe uniquely qualified—to save the things about it that many neoliberals profess to cherish, things that may otherwise suffer a grim fate.

To see what I mean, you have to first appreciate an odd thing about the word “neoliberal.” Unlike most ideological labels, it is claimed by virtually no one. It’s used mainly as a pejorative, typically to mean something like “a free market fundamentalist who happily does the bidding of corporate overlords, helping them run roughshod over the world’s working people.” And that’s not the kind of phrase you put in your LinkedIn profile.

But even if no one wears the neoliberal label proudly, and even if the term is now thrown around so loosely as to make it unclear who really merits the label, it’s possible to apply it with some precision. If you follow the term “neoliberal” back to the 1990s, you’ll find it referring to a distinct set of policies—policies collectively called “the Washington consensus”—and an underlying philosophy. Adherents of that philosophy are still around, and many of them—neoliberals in a precise and not-necessarily-pejorative sense—are now being called neoliberals in the vaguer, pejorative sense.

These are the people I’m calling neoliberals, and here is the point I want to make about them: If their detractors are right—if they are mere tools of rapacious capitalism, cloaking their true motives in liberal cliches—then they should definitely oppose Sanders. But if their goals are the more high-minded ones that they profess, Sanders may be their man and Joe Biden may not.

The Washington consensus was a view, prevalent in Washington-based institutions like the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the US government, about how countries should structure their economies—a view that struggling countries often had to accept if they wanted aid from those institutions.

The prescription these countries got was heavy on free-market medicine: privatization, deregulation, opening up to freer trade and to foreign investment. And there was an emphasis on fiscal responsibility that sometimes meant cutting government services (though the Washington consensus did encourage spending on public education, health care, and infrastructure).

When these policies went awry—when, for example, the “shock therapy” of sudden fiscal austerity hurt a country’s workers and destabilized its politics—the “neoliberal” philosophy naturally got the blame. Hence the pejorative sense of the term, which only got stronger as the Washington consensus was linked to other kinds of trouble—as the free flow of capital was implicated in the 1997 Asian financial crisis, and as free trade was blamed for shuttered factories and stagnant wages in America and other affluent nations. (There was at least one other meaning of “neoliberal” prevalent in the 1990s, but it’s the “Washington consensus” meaning that led most directly to the pejorative use of the term, and that’s the meaning that’s relevant to this argument.)

So what do people who backed the Washington consensus have to say for themselves? What would Bill Clinton—who not only backed it but helped implement it—say his motivations were?

I have some relevant experience here. My book Nonzero, which came out 20 years ago, had some nice things to say about globalization, international trade, and even about a big bete noire of the left, the World Trade Organization. The book was embraced by Clinton, who is now viewed on the left as among the most nefarious neoliberals (rivaled in nefariousness, perhaps, by his wife). Clinton mentioned my book in more than a dozen speeches, had White House staffers read it, and told Foreign Policy Magazine that it had a “huge effect on me as the president.”

That last part may merit a grain of salt; when the book came out he had barely more than a year left in office. Still, his descriptions of the book—including in a brief conversation with me—make it clear that he broadly shared its view of globalization, and that it reflected the hopes he had for the neoliberal order he helped build. Looking at the fate of those hopes twenty years later, we can see both why that order is imperiled and why Sanders, however ironically, may be better equipped than Joe Biden to save the parts of it that are worth saving.

For Clinton, the aspirations behind the Washington consensus fit into a larger vision of the post–Cold War world that he hoped to usher in. Prosperity would spread to poorer countries, and in the process the world’s nations would be drawn together via economic interdependence. Such a world would be well positioned to sense and act on other areas of interdependence—cooperating to address climate change and other environmental challenges, as well as problems like global pandemics and the proliferation of chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons.

In short, nations would recognize that they’re playing lots of non-zero-sum games (hence the title of my book)—games that could have win-win outcomes if they collaborated wisely and lose-lose outcomes if they didn’t. As global governance evolved to mediate this collaboration, the world would cross the threshold into a true global community.

At least, that was the hope. People who still share this hope—which includes lots of prominent Democrats, certainly including many who are called neoliberals—face a question: Which of the 2020 presidential candidates is most likely to use the White House to help us move closer to that vision?

Obviously not Trump. He explicitly and generically rejects “global governance,” and he has worked against particular manifestations of it such as the Paris accord on climate change and various arms control agreements.

Indeed, Trump is a threat not just to the global governance that is indirectly tied to the Washington consensus—the kind that is facilitated by the web of economic interconnection the consensus aimed to build—but to the kind that sustains the web itself. He has paralyzed the World Trade Organization’s dispute resolution mechanism by blocking the appointment of judges (perhaps to evade judgment of his more dubious unilateral trade tactics).

So the question becomes: Is Joe Biden or Bernie Sanders more likely to pave the way for the world Clinton envisioned and Trump rejects? The first step toward answering that question is to underscore one of the big upsides of the Washington consensus and its relationship to one of the downsides.

[To read the rest of this piece (or to get the link to use for sharing the piece) click here.]

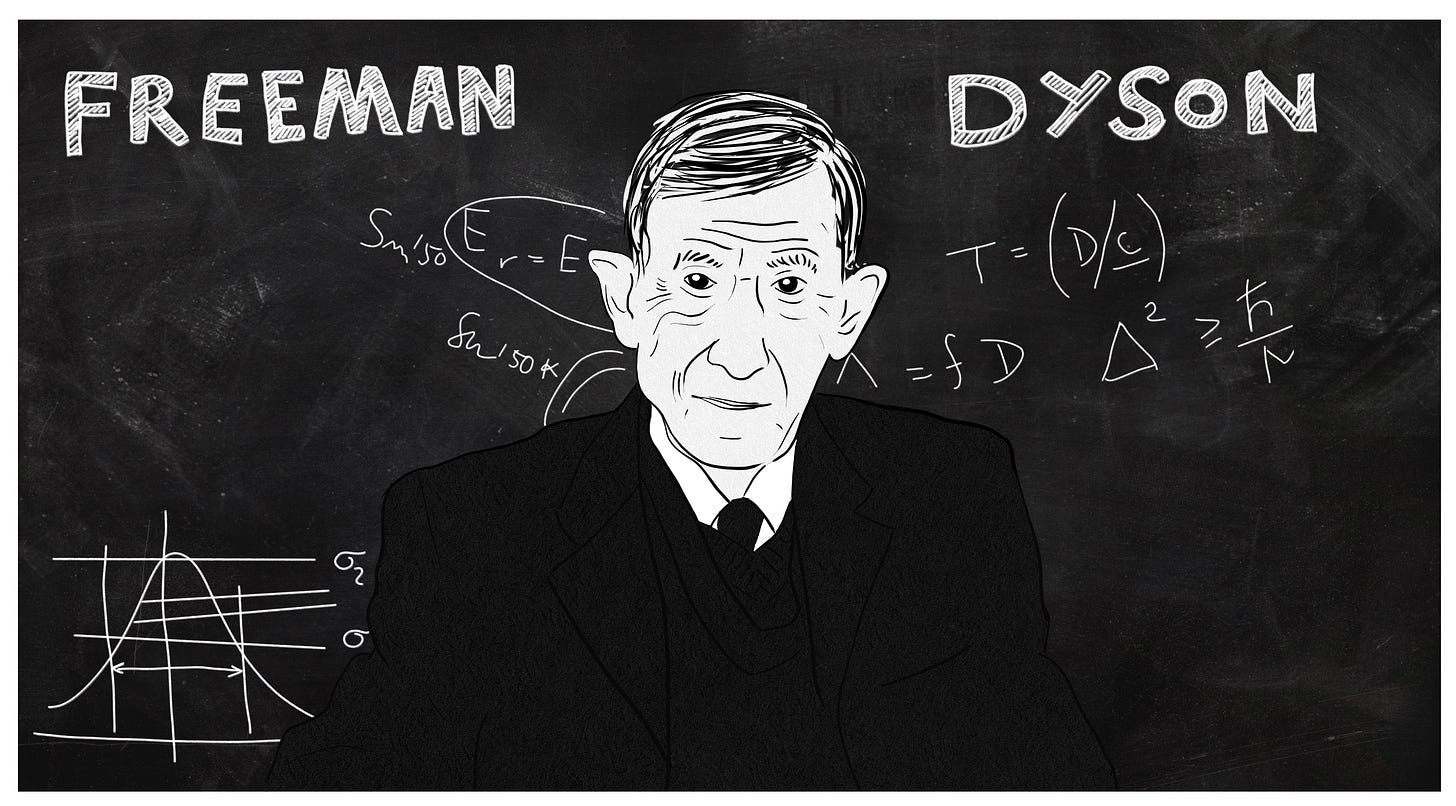

Freeman Dyson (1923-2020)

The New York Times obituary of the physicist Freeman Dyson, who died a week ago, includes such characterizations as “iconoclast,” “heretic,” “visionary,” and “religious, but in an unorthodox way.” All of that and more came through in an interview I did with Dyson two decades ago (one of the very first video interviews I ever did, back at the dawn of online video). Below is a mildly edited transcript of the interview. Reading it, I was reminded how eclectically adventurous Dyson was—jumping from the Gaia hypothesis to an eccentric definition of God to the idea that the universe involves “three levels of mind” and to many other things. I was also reminded what a nice person he was.

ROBERT WRIGHT: First of all, thanks very much for letting me come talk to you here today. I've never been within the walls of the Institute for Advanced Study before, and I feel kind of privileged. It has a kind of mystique about it. Do you find that people react to it that way?

FREEMAN DYSON: Well, I tried to demolish this aura of sanctity that surrounds the place. What it is basically is a motel with stipends. ... It's just a place where young people come from all over the world and are given a year or two with pay.

A somewhat more selective admissions policy than some motels have. Right?

Yes. But still that's basically what it is. Mostly the important thing is what they do when they get home, not what they do while they're here.

I see. But there have been—I mean, Einstein, von Neumann and so on—there have been a lot of people thinking deep cosmic thoughts here, right?

Yes, but that's not really what the place is for, that's accidental.

It's not for cosmic thoughts really?

Well, if you're lucky, of course you get a few of those. ...

You, in any event, have been doing your share of thinking cosmic thoughts.

Not very much.

Well, I don't know. Let's do a brief review.

You wrote a paper some time ago on the question of whether life could survive indefinitely in an expanding universe.

Right.

You invented this concept of what's now called the Dyson sphere, which crops up in the science fiction literature sometimes.

Yes. Both of those items really have nothing to do with work. Those were, both of them, essentially just little jokes. It's amusing that you get to be famous only for the things you don't think are serious.

You've done a good job of not being serious then.

[You can read the rest of this dialogue at nonzero.org.]

In the New York Times, Peter S. Goodman writes that the coronavirus has “accelerated and intensified the pushback to global connection,” heightening fears about immigration and exposing the vulnerability of global supply chains. And the pushback may be just beginning. As Jeet Heer notes on Twitter, Trump’s initial, optimistic messaging strategy—Don’t worry, we’re on top of this—may soon give way to xenophobic, anti-globalization fear mongering. Secretary of State Pompeo has already started calling the virus the “Wuhan virus.”

Elizabeth Preston reports in Quanta that the aquatic salamander known as the axolotl—which looks even weirder than its name suggests—has now had its genome fully sequenced. The resulting knowledge could someday give humans a quintessentially axolotlic skill: the ability to regenerate lost body parts.

In Fast Company, tech writer Harry McCracken takes a look at the presidential campaign of 1996, “the first to be fought on the web.” It wasn’t a momentous battle; most voters weren’t on the web, and “nobody in politics was an expert on leveraging its power.” McCracken says the candidates’ websites were “eyesores…even by 1996 standards”—and a perusal of them provides some supporting evidence. But I was most struck by the air of innocence and earnestness. The home page of Phil Gramm’s site declares, “We have established this presence on the internet in the interest of providing a wide range of news and information that will interest those who are already involved in our campaign and those who want to learn more about our efforts.” That it took only 20 years to get from there to 2016—when the web was a battleground of bot-abetted, microtargeted deception—is sobering.

The Trump administration’s support of the bloodless coup that deposed Bolivian President Evo Morales hasn’t wavered amid the repression unleashed by his military-installed successor, to judge by a piece in the Washington Post. And, to judge by another Post piece, the justification for that coup is looking even shakier than before. A statistical analysis by two MIT scholars casts doubt on the claim that there were “voting irregularities” suggestive of foul play by Morales.

I’ve never been good at lovingkindness (“metta”) meditation. (People who know me aren’t mystified by this.) In Tricycle, Thai forest monk Ajahn Brahm suggests that metta-challenged meditators like me start the practice by imagining a kitten. No way, dude. But I’m willing to try a dog. Anyway, this short article is linked to Tricycle’s annual Meditation Month—a challenge to commit to 31 days of (not-necessarily-metta) meditation, along with a package of materials that help.

In the New York Times, Alex Stone looks at a demographic of growing interest to scholars of marketing: people who are consistently drawn to new products that will wind up bombing in the marketplace. These “harbingers of failure” may someday be used by companies to abort the launch of doomed products (whose past examples include Crystal Pepsi, Watermelon Oreos, and Cheetos Lip Balm.) Apparently there are whole zip codes whose residents seem to have this sixth sense.

The recent peace deal between the US and the Taliban looked tenuous this week as Taliban attacks on Afghan government targets brought American counterattack. John Glaser of the Cato Institute argues that the deal will remain fragile so long as the US continues to make compliance with it conditional on constructive engagement between the Taliban and the Afghan government, rather than acknowledge the limits of American leverage.

On the Wright Show, I interviewed alleged Bernie Bro David Klion, author of a tweet so notorious that Mike Bloomberg featured it in an ad implicitly aimed at Bernie Bros. I thought I had convinced Klion that it would be a good idea to tone down his more hyperbolic, tribalistic tweets, but a few days later he tweeted this. Sigh.

OK, That’s it! See you next time. If you haven’t done the thing we routinely implore you to do—follow us on Twitter—it may be time for you to do some soul searching. And if you have thoughts about this issue that need expressing, email us at nonzero.news@gmail.com or make use of the comment section at the bottom of the web version of the newsletter on Substack.

Illustrations by Nikita Petrov.