Welcome to what is, for obvious reasons, one of the less lighthearted issues of NZN. But it’s not unrelievedly grim! For example: I examine an intriguing new proposal for fighting the coronavirus pandemic without courting global economic collapse. And, in an all-coronavirus edition of the Readings section, I highlight a few positive side effects of the pandemic. But first, in the two pieces immediately below, I ask whether COVID-19, being a peril to all of America and all of the world, will exert a unifying effect on them. Or will it wind up deepening divisions within the US and/or between nations? (Hint: Donald Trump will have something to say about this.)

The China Derangement Syndrome

Did you know that “America is under attack—not just by an invisible virus, but by the Chinese”? Did you know that, even amid this attack, “Joe Biden defends China and parrots Communist party propaganda”? If not, maybe you should get on the mailing list for news updates from the Trump-Pence campaign.

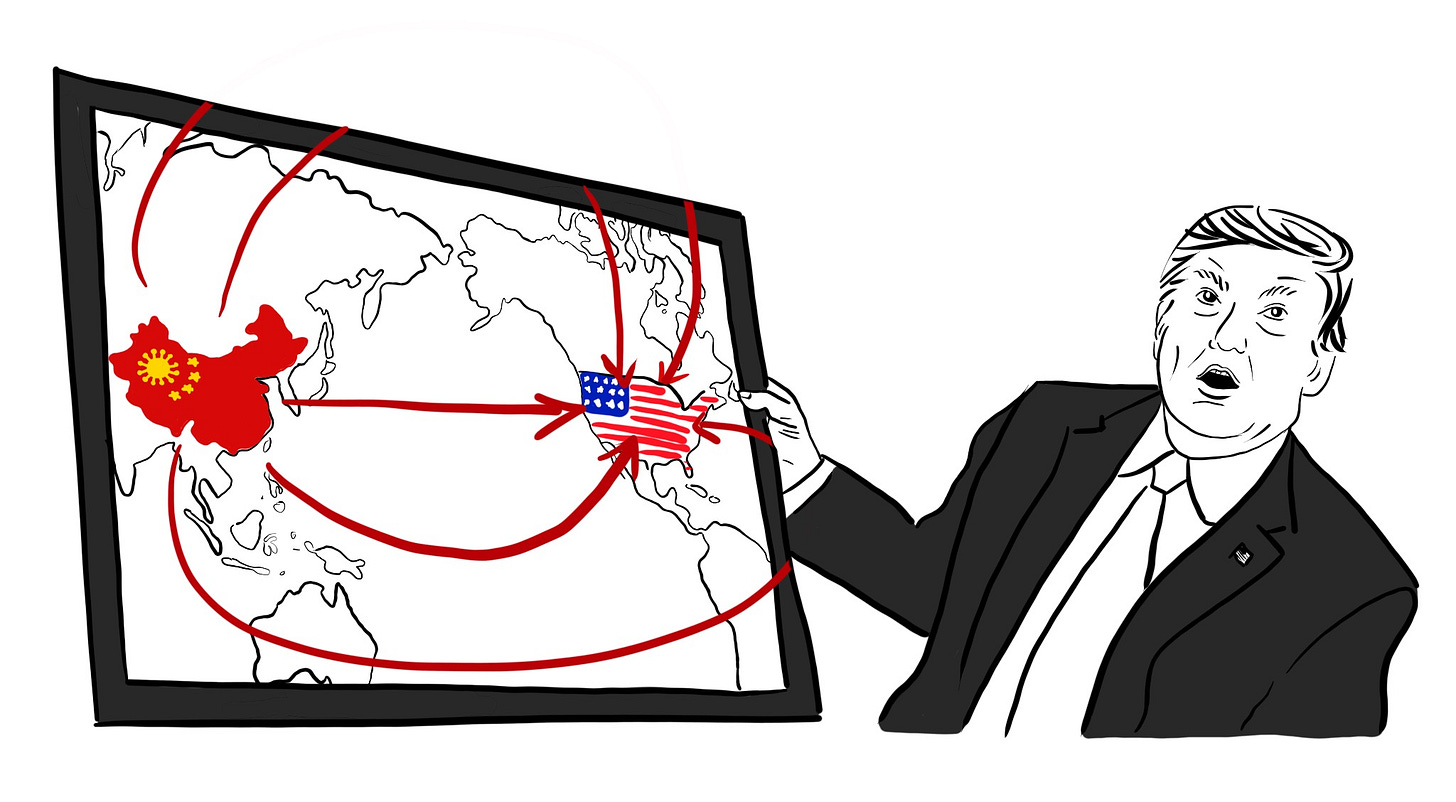

Team Trump has shifted into full-on blame-China-first mode. In a span of two weeks, we’ve gone from Trump using the term “coronavirus” to Mike Pompeo test-marketing the term “Wuhan virus” to Trump abandoning all pretenses of subtlety and going with “Chinese virus.”

There’s no denying that China deserves lots of blame. Its failure to adequately regulate Wuhan’s “wet markets”—where wild animals are sold for consumption—seems to be what inflicted this epic problem on the world.

Then again, in 2008 America’s failure to adequately regulate its financial markets inflicted an epic problem on the world. That’s life amid globalization: screwups in one nation can rapidly infect other nations. Sometimes you’re the screwer, and sometimes you’re the screwee.

To put this in more formal language: in a globalized world, nations are locked into a non-zero-sum relationship; there can be lose-lose outcomes or win-win outcomes, depending on how they play their games. This pandemic has been lose-lose, but in the fight against it there will be win-win moments—not just in the sense that victories over the virus in any nation make other nations safer, but in the sense that successful tactics and treatments discovered by one nation will spread to other nations. For better and for worse, we’re all in this together.

One of the main things this newsletter is about (hence the name!) is how the world’s various non-zero-sum games can be played more wisely. Sometimes that mission means championing the kind of global governance that facilitates cooperation among nations. So, for example, I’d be against cutting US funding to the World Health Organization. And I’d certainly be against trotting out the idea of a 50 percent cut in that funding at exactly the time that a pandemic is enveloping the world—which, remarkably, the Trump administration actually did.

But cheering for good global governance isn’t enough. If you’re serious about fostering it, you have to foster a political climate conducive to it, which means fighting the xenophobia and crude nationalism that so often poison that climate.

You may think my next sentence is going to be: “And that means fighting Trump and Trumpism.” Wrong!

I mean, it goes without saying that you have to fight Trump and Trumpism. But Trump and his supporters aren’t the only problem. If they’re going to sustain enough xenophobia and crude nationalism to keep global governance in the primordial ooze phase of its evolution—where it’s been mired for some time now—they need some help from mainstream voices.

And they get it! The US foreign policy establishment—aka the Blob—in various ways helps sustain the tensions with other nations that make advances in institutionalized cooperation hard.

Consider a piece published this week in the Atlantic (a pillar of the liberal-hawk part of the foreign policy establishment) by Shadi Hamid, a fellow at the Brookings Institution (another pillar of the liberal-hawk part of the foreign policy establishment). Hamid—whom I know a bit and respect a lot—is a good example of the problem because he’s not himself a xenophobe or a crude nationalist. But by advancing the Blob’s moralistic framing of foreign policy questions, and by sharing the Blob’s tendency to exempt America from the degree of moral scrutiny it brings to other nations, he winds up unwittingly abetting xenophobia and crude nationalism.

Hamid’s Atlantic piece defends Trump’s blame-China framing of the pandemic and concludes that, after the crisis subsides, “the relationship with China cannot and should not go back to normal.” Because “this pandemic should, finally, disabuse us of any remaining hope that the Chinese regime could be a responsible global actor. It is not, and it will not become one.”

My problem with this piece isn’t that it makes no valid criticisms of China. It’s true, for example, that after Wuhan officials were notified of a cluster of strange illnesses in late December, they spent days trying to keep this information from the public, even going so far as to detain doctors who talked about it.

And after Chinese officials did go public about the outbreak, they tried to downplay the peril it posed, even concealing information about it—so, all in all, it took nearly four weeks for Wuhan City to be shut down. (Hamid says the shutdown came “seven weeks after the virus first appeared.” Technically true, but misleading: when the virus appeared, doctors didn’t grasp its significance; they didn’t report it to local officials until three weeks later.)

This delay is reprehensible and turned out to be massively consequential, and we should complain about it. But it’s not shocking, given the tendency of institutions to try to conceal unflattering news. For example: The Life Care Center nursing home in Kirkland, Washington had by February 10 started discouraging visits because patients there were suffering from a strange flu-like illness that turned out to be COVID-19. But, as the Washington Post reported, the nursing home didn’t notify local officials of the problem until 17 days later—even though it was required by law to notify them of flu cases within 24 hours.

And as for the fact that some Chinese officials soft-pedaled the threat of the disease even after disclosing it: Again, worth complaining about. But if you’re an American who is using this as a key plank in your argument that the Chinese regime can never, ever be “a responsible global actor,” maybe you should at least acknowledge that your own president famously and catastrophically soft-pedaled the threat posed by COVID-19 long after Chinese officials deemed it a grave peril and the World Health Organization declared a public health emergency.

Hamid, though, doesn’t even mention this. Instead he chastises those who “seem comfortable drawing moral equivalencies between the Chinese regime and Donald Trump” and then declares, “I, for one, am glad to live in a democracy, however flawed, in this time of unprecedented crisis.”

I, for one, am too. And I’m not saying Donald Trump is morally equivalent to Xi Jinping (though, God knows, he’d be closer to that if he thought he could get away with it).

Nor do I approve of, for example, a Chinese official suggesting that hundreds of US military personnel who visited Wuhan last fall may have brought the virus to China. (Though, to be fair, that seems to have been retaliation for semi-deranged Republican Senator Tom Cotton, a frequent Trump ally, having suggested that the virus emerged from a Chinese bioweapons lab.)

In fact, there are tons of things I don’t like about the Chinese government’s behavior—first and foremost that it has forced God-knows-how-many Muslims into “education” camps, where “teachers” try to expunge their cultural heritage from their brains.

And if I thought that ostracizing China—or doing whatever Hamid has in mind when he says relations with China should never “go back to normal”—would bring relief to its Muslims or to Chinese in general, I’d seriously consider the idea. But decades of experience tell us that when we go beyond denouncing human rights violations and try more forceful measures, we often make things worse, not better. There are good moral arguments against the current governments in Iran and Venezuela, but those arguments have been deployed to inflict huge suffering on the people in those countries via crippling economic sanctions—and the governments, in response, have grown only more repressive.

Meanwhile, common sense tells us that pragmatic engagement with all the world’s countries is essential given the number of non-zero-sum games we’re playing with them—in the realm of health, for sure, but also in realms like environmental policy and arms control. (Tom Cotton is right to worry about bioweapons labs abroad, though he’d never sign onto the kind of intrusive global governance required to handle the threat.) Common sense also tells us that to weather the current crisis we may need to play any number of ad hoc non-zero-sum games with China—like, say, the multinational coordination of monetary policy to stave off economic collapse. So maybe vilifying China right now is kind of stupid.

Hamid correctly writes that “China has a history of mishandling outbreaks, including SARS in 2002 and 2003.” But his claim that China’s “negligence…after the first outbreak” of COVID-19 “far surpasses those bungled responses” is strange. SARS had been circulating in China for more than two months before it was reported to the World Health Organization. COVID-19 was reported to the WHO four days after a doctor brought it to the attention of Wuhan health officials.

In other words, the coronavirus episode suggests that China has, in at least some important ways, become a more responsible global actor—demonstrating exactly the kind of improvement that, according to Hamid, the coronavirus episode proves China is incapable of demonstrating.

When this pandemic finally passes, the world’s nations should have a candid conversation about what allowed it to happen, and decide how to strengthen national and international institutions in ways that could prevent a repeat. If people like Trump and Tom Cotton—with the assistance of influential Blobsters who seem incapable of escaping the perceptual and cognitive distortions that accompany American exceptionalism—continue to gratuitously deepen tensions with China, that will be a lot harder than it needs to be.

To share the above piece, use this link.

Red virus, blue virus

On March 11—back before President Trump had declared a national emergency and sent various other signals that he was now taking COVID-19 seriously—the Economist posted some numbers showing that Democrats were more worried about the virus than Republicans and more likely to have taken precautions against it. The headline said, “In America, even pandemics are political.”

There’s certainly some truth to that. Once Trump, out of the gate, minimized the dangers posed by the virus, some of his supporters followed their leader—as supporters are especially inclined to do in polarized times. And their attachment to his position was probably strengthened by the derisive dismissal of it coming from his detractors. Psychology of Tribalism 101.

But to fully appreciate the coronavirus’s potential to deepen American polarization, you need to see how thoroughly it can be woven into the narrative that got Trump elected. And to see that, you need to understand another reason Trump supporters didn’t get as freaked out by the virus as Trump detractors: It wasn’t as much of a threat to them.

The virus was at first a blue-state problem: California, Washington State, New York, and Massachusetts had the biggest spots on the coronavirus map. And as the disease spread, it hit the bluer parts of the red states—the big cities. (As various analysts have noted, America’s great divide isn’t so much blue state versus red state—after all, big chunks of blue states are red, and vice versa—as high-population-density areas versus lower-density areas.)

Of course, this is changing. The virus is now in all states, and it’s starting to move from cities to towns. So maybe people on both sides of America’s political divide will more and more be seeing things the same way?

In the sense of taking the epidemic seriously, yes. There’s been an uptick in Republicans’ interest in and concern about the coronavirus as it has spread and as Trump has gone from being dismissive of it to being conspicuously in command of the war against it. But there’s reason to worry that this convergence of perspectives won’t bring broader harmony between red and blue.

For one thing, if you’re in a red state or a red town, and you see the virus headed your way, where is it headed from? From blue states and blue cities! Moreover: How did it get to those blue states and blue cities? From abroad.

This image—blue America as a conveyer belt for foreign menace—fits nicely into the core narrative of Trumpism. It’s a narrative not just about the perils of global interconnection but also about the American coastal elites who abet it, who support and profit from unbridled international trade and easy immigration. In one version of this story, the coronavirus would never have reached our shores had these cosmopolitans not been flying around the globe, mingling with foreign elites rather than with the ordinary Americans they secretly disdain. COVID-19, a cell less than one ten-thousandth of an inch long, may be the most compact embodiment ever of Trump’s key campaign themes: nationalism, xenophobia, and populist resentment of America’s coastal cosmopolitan elites. It is a living link between Trump-designated foreign enemies and Trump-designated domestic enemies.

Or maybe this is all in my head. I have a tendency to fret about dire scenarios that have yet to unfold. For now, at least, much of red America still doesn’t sense enough peril to start blaming people for it. As Trump said at Friday’s press conference, even as New York and California are “hotbeds” of contagion, “you go out to the Midwest, you go out to other locations, and they’re watching it on television, but they don’t have the same problems. They don’t have by any means the same problem.”

But even this difference of perspective can be divisive, as blue Americans ask for federal help and some red Americans champion a stew-in-your-own-juice policy. After my wife complained on Facebook that Trump hadn’t yet used his emergency powers to get more facemasks and ventilators manufactured in anticipation of likely shortages in New York City (where our daughters live), a Trump-supporting nephew of mine replied that “The President of the United States isn’t responsible for everything that happens to the entire population of the country.” He suggested that my wife direct her pleas to New York officials. “But the local government is far left so of course it’s not their fault, right? Well you should hold your local government responsible. Because they are.”

Meanwhile, even if Trump isn’t spelling out the whole blue-states-as-foreign-menace-conveyers narrative, he’s certainly playing up the foreign menace part. Calling COVID-19 the “Chinese virus” not only diverts blame from his early inaction but pushes some of the nationalist and xenophobic buttons that got him elected. And supportive commentators even in fairly high-brow journals are fleshing out the narrative a bit further—asserting, for example, that the predicament the virus has left us in should be blamed on both the nefarious Chinese and on America’s embrace of heedless globalization.

Two weeks ago, in The Week, Damon Linker argued that the coronavirus would strengthen Trump’s brand of nationalism not just because the virus came from abroad but because of the very nature of contagious disease. “Nationalism is a politics of fear and threat,” he wrote. “The fear of falling prey to the pandemic inspires suspicion of newness and crowds and ‘others’ of all kinds. We long, instead, for safety and protection, for cleanliness and purity. For the comfort and security of home.”

For this and other reasons, Linker predicted that the coronavirus will strengthen and even expand populist nationalist movements not just the United States but in other countries where they’ve taken root: Poland, Hungary, Brazil, Germany, France, and elsewhere.

The silver lining in Linker’s analysis was his belief that, as the epidemic spread, supporters of Trump would likely see that his early nonchalance about it was wrong and costly. In a conversation with me on The Wright Show podcast, Linker said it was reasonable to hope that Trump supporters would conclude that “the liberals who were up in arms about this virus weren’t completely crazy”—and the result might be an America with “not just conflicting narratives” but “more of a shared reality.”

I hope that Linker’s right—that, even if COVID-19 is good for Trumpism, it could help discredit Trump. But at the moment Trump’s approval numbers are roughly where they were two weeks ago, back when he was minimizing the threat posed by the virus and before it had invaded all 50 states. And approval of his handling of the epidemic has actually risen. The “rally round the flag” effect of national crises is famously strong, and it would take salient and sustained ineptness on Trump’s part to wholly negate it.

If Trump wants to fully harness that effect—which you’d think he’d want to do in an election year—he presumably will subdue his more egregiously polarizing tendencies. He might even use this opportunity to try to unify the nation. And—who knows?—he could even go whole hog and try to unify the world. But if he instead opts for his default mode of national and international divisiveness, this virus has given him plenty of raw material to work with.

To share the above piece, use this link.

Killing COVID-19 without killing the economy

Our situation would seem to be this: the price of fighting COVID-19—the price of the massive social distancing the U.S. and other countries are now deploying against it—is almost certainly a recession and possibly a global depression. And global depressions have, among other downsides, something in common with COVID-19: they kill people.

In the New York Times, David L. Katz, a physician, argues that there’s a way out of this dilemma—a way to avert economic collapse without paying a massive toll in death and suffering.

The basic idea is to apply social distancing more selectively but more intensively: identify the most vulnerable (older people, plus younger people with such conditions as diabetes), and strengthen the rules that protect them from infection, while relaxing the rules for the less vulnerable, and thus allowing them to participate in the economy.

In this scenario, the contagion would continue, but it would continue within corridors that would keep the death rate low—that is, corridors occupied by relatively young and healthy people. The typical experience of people infected would range from feeling no symptoms at all to having something like a bad case of the flu. And after infection they would presumably be immune, at least for a while. Eventually America would achieve “herd immunity”: a high enough percentage of the population would be immune so that the virus would quit spreading.

Most people, including me, find “herd immunity” scenarios a bit chilling, as they entail unflinching resignation to a certain level of death, however low, within a certain part of the population. And that just seems less humane than trying to save everyone, even if that effort is doomed to fall well short of its goal. But before dismissing Katz’s idea, you should read his op-ed, because he notes downsides of the current approach (including lethal ones) that go beyond flirting with economic apocalypse.

Besides, you can imagine more moderate versions of his plan. We could, for example, try to slow the rate of transmission within the corridor of contagion, thus providing more time for a vaccine, or at least powerful anti-viral treatments, to emerge. (The standard expectation is that we’ll have anti-viral treatments that save at least some lives before we have a vaccine.) We might even draw on the growing population of immune people to fill jobs that involve lots of public contact, like supermarket checkout clerk, waiter, or postal worker. And we could encourage some measure of social distancing even among the young. (And, of course, anyone of any age would be free to exercise as much social distancing as they wanted.)

I think the broad-gauged social distancing we’re practicing in New York, California, and other hot spots makes sense for the time being. It’s our best chance to slow the epidemic before it overwhelms hospitals, and it will give us time to get a clearer sense of where things stand—how prevalent the disease is, and how lethal it is. (Various pieces of evidence suggest that the death rate may be significantly lower than the rate reported in China, and the lower it is, the less chilling is Katz’s proposal.) And if we do decide that a model like Katz’s makes sense, we need time to set it up.

My father grew up in west Texas amid the Great Depression. His father was a sharecropper, and good medical care was remote, and by the time my father was 14 both of his parents and three of his siblings had died. I’ve always assumed that affluence would have saved some of them, but I’ve never known for sure whether it was accurate to say that the Great Depression killed some of my ancestors. In any event, we know for sure that it killed some people and inflicted deep suffering on others.

We tend to assume that there won’t be another such calamity—that even if there is something that qualifies as a global depression it won’t be as cruel and lethal as the last one. But the truth is we don’t know what a worldwide economic collapse in the modern era would be like. I’m willing to entertain even chilling ideas if they offer a way to avoid finding out.

To share the above piece, use this link.

New York Times tech writer Kevin Roose sees upside in the physical isolation the coronavirus has imposed on us. The virus “is forcing us to use the internet as it was always meant to be used—to connect with one another, share information and resources, and come up with collective solutions to urgent problems. It’s the healthy, humane version of digital culture we usually see only in schmaltzy TV commercials, where everyone is constantly using a smartphone to visit far-flung grandparents and read bedtime stories to kids.”

Pollution dropped markedly in China and Italy as a result of coronavirus-induced social distancing. On the environmental blog G-Feed, Marshall Burke calculates that the lives saved in China via reduced pollution exceeded the lives lost to the virus. Whether or not that’s true, the satellite images accompanying the blog post are testament to how much the air seems to have cleared up in China. Satellite shots of northern Italy before and during its lockdown paint the same picture. Of course, these reductions in pollution were part of an economic slowdown that you wouldn’t want to sustain forever. Still, the pandemic will no doubt heighten our appreciation of how many things we can do remotely, via information technology, without generating as many pollutants as we’re accustomed to generating. These things include not just telecommuting but, for example:

Quartz reports that the pandemic has brought a boom in telehealth, as doctors—in part to shield themselves from infection—become more amenable to virtual office visits.

In the New York Times, John Schwartz assesses the extent to which some of the tools of social distancing—telecommuting, virtual conferences, and the like—could slow the rate of climate change. The question is more complicated than you might guess. If, for example, working remotely means spending the day in a house that would otherwise be uninhabited, the fuel consumed to heat or cool the house has to be weighed against the fuel saved by not commuting (which itself varies greatly depending on whether you drive to work or take public transportation).

Tricycle is offering free online meditation sessions “to help ease anxiety amid our social-distancing efforts.” And Dan Harris’s Ten Percent Happier website offers a free “coronavirus sanity guide.”

OK, that’s it! If you still haven’t had enough of me, you can watch me discuss the coronavirus and other things with NZN artist-in-residence Nikita Petrov on the Patreon site (where you could also, by the way, become one of our cherished Patrons). And by tomorrow I’ll have posted a Wright Show podcast with psychologist Paul Bloom about the coronavirus. I close with the usual exhortations: Follow us on Twitter, share content you think is worth sharing, and email us with feedback: nonzero.news@gmail.com. Also: stay safe and try not to endanger others.

Illustration by Nikita Petrov.