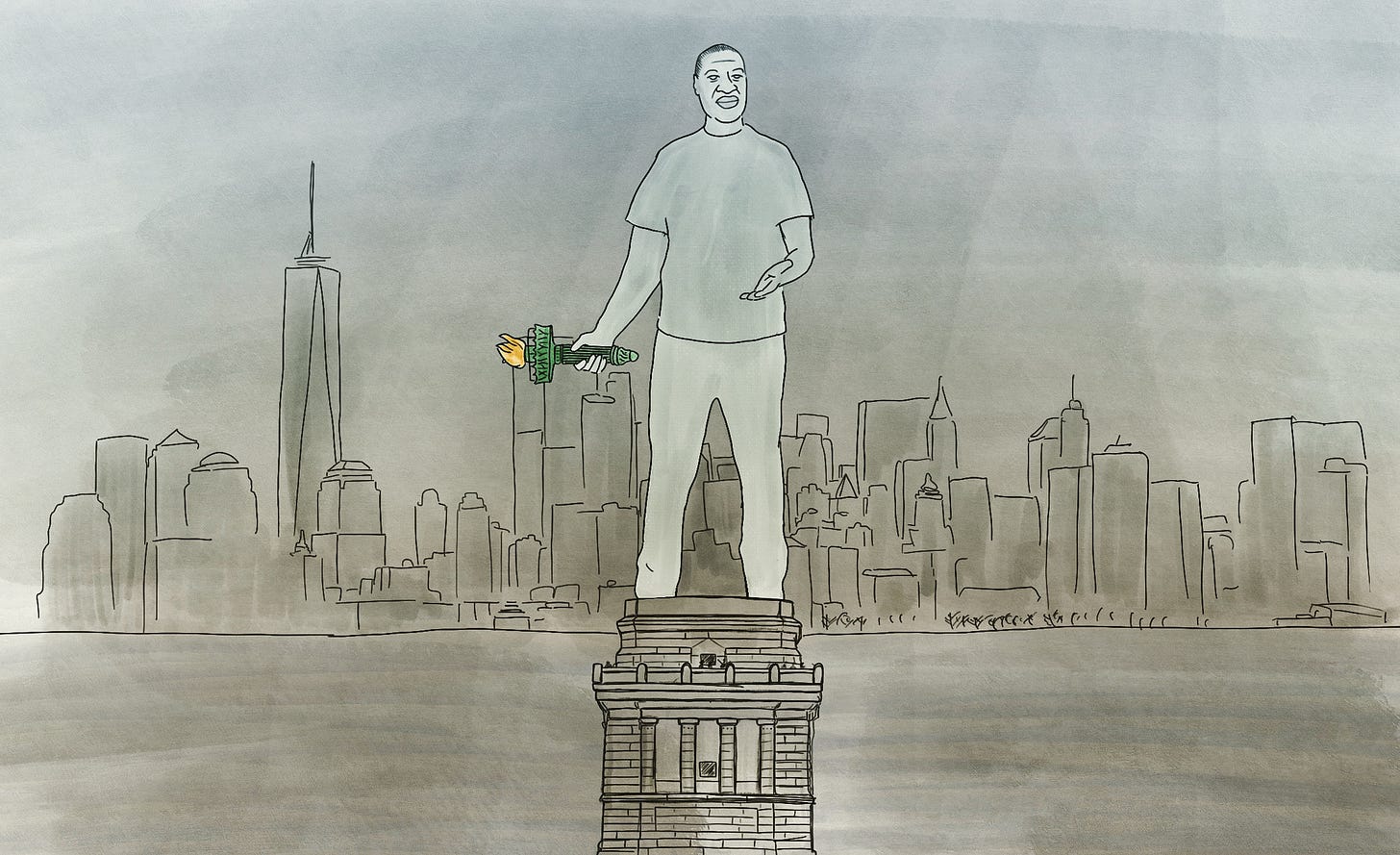

Let’s make the George Floyd moment bigger!

Plus: Does consciousness pervade the physical world? And readings on ADHD’s upsides, Bolton’s downsides, canceled Roman statues, etc.

This issue of the newsletter borders on being a magazine—there’s a whole lot of words (and pictures) in it! In consecutive pieces, I argue for using the George Floyd moment to push for (1) an ambitious policy agenda that I think would make life better for the George Floyds of tomorrow (and might reduce racism in the meanwhile); and (2) a foreign policy that involves less in the way of killing and oppressing the less privileged people of the world. Then I ponder, in conversation with philosopher Galen Strawson, whether consciousness is something that pervades the physical world (and whether “physical” is the right word for the physical world). Plus, I note the emergence of a thriving Black Lives Matter meditation community and steer you to readings on such things as: the hidden virtues of having ADHD; what the Romans can teach us about tearing down statues; a John Bolton listicle; the death of the two-state solution; the meaning of “the Great Awokening;” and whether the Black Lives Matter protests have been co-opted by establishment elites.

Can we make the George Floyd moment even bigger?

Here are some things that have grown out of the social and political ferment catalyzed by the killing of George Floyd:

1) Merriam Webster says its dictionary entry for “racism” will be amended to “make the idea of systemic or institutional racism even more explicit in the wording of the definition.”

2) The TV show COPS has been canceled, and police cars have vanished from the bestselling video game Fortnite.

3) Github, the Microsoft-owned company that runs the world’s biggest site for software developers, plans to get them to quit using the word “master” to refer to the main branch of a computer program’s code.

I’m sure things like this can do some good. Language and culture influence our attitudes more than we realize (if not always in uniform ways; in my own experience, COPS often stirred empathy for the people arrested and underscored the pointlessness of jailing them). And particular words, like “master,” can offend some people in ways others are oblivious to.

Still, it does seem to me that an inordinately large number of the initiatives spawned by the Black Lives Matter protests lack a certain… concreteness.

There is, of course, one concrete-sounding proposal emerging from the protests: “defund the police.” But many people who espouse it spend lots of time explaining that they don’t mean what you might think they’d mean by “defund the police.” And the ones who say they do want to actually abolish police forces are advocating something so unpopular that, for now at least, we can forego discussion of it.

I’m just a random old-fashioned white guy, and it’s possible that my identity is blinding me to momentous change, happening even as I write, that will enduringly improve the lives of people of color. Certainly there will be some worthwhile reforms (including some being discussed under the unfortunate rubric “defund the police”). And certainly the George Floyd protests have brought commitments from big companies—to diversify workforces, to set aside money for laudable programs—that could wind up making a sizable difference. Still, precisely because I’m old-fashioned, I’d hate to see a moment so packed with political energy pass without leaving a legacy of an old-fashioned kind: momentous changes in public policy, including some well-funded ones (where “well-funded” translates as “Can we finally get serious about raising taxes on rich people?”).

So I say we think big! Let’s imagine converting this energy into large-scale policy change that would honor the memory of George Floyd and address injustices highlighted by his death. What follows are two proposals, one in the realm of domestic policy and one in the realm of foreign policy. (Yes, foreign policy—that’s how big I think we should think!)

George Floyd, racial justice, and economic justice

Last week the New York Times ran a piece depicting Bernie Sanders as woefully out of step with the current political moment by virtue of his tendency to see the world through the prism of economic class, not ethnic identity. Calls from the Black Lives Matter movement “to address systemic racism and police brutality,” said the Times, are resonating in a way that “Mr. Sanders’s message of economic equality did not.”

It’s true that we’re hearing very little about that favorite Sanders theme of raising taxes on high-income people and using the money to help low-income people. By and large, the George Floyd story is being seen as a story about racial injustice and not about economic injustice.

I think that’s a mistake, in two senses.

First, it’s a tactical mistake for the left. This is a moment full of activist energy, and it’s opened up new political space; there’s a chance to push for radically increased government spending on, for example, education, housing, and health care for low-income people. Such spending disproportionately helps black people, and to pass it up because it’s technically about class, not race, would be wasteful to say the least.

Second, it’s a conceptual mistake. Racial justice and economic justice are deeply connected, as has been noted by a number of people, including Martin Luther King, Jr. (“What does it profit a man to be able to eat at an integrated lunch counter if he doesn’t earn enough money to buy a hamburger and a cup of coffee?”) If we’re going to launch a serious attack on racism, it needs to include a serious attack on economic inequality.

Or, to put it another way: If we want to help as many as possible of the George Floyds of the world, we need to see the story of George Floyd in wide angle. It’s not just the story of a black man dying at the hands of a brutally indifferent white cop. It’s the story of a black man whose circumstances of birth, like those of many black men, made it likely from the get-go that he’d have antagonistic encounters with police, and that these encounters would lead to various kinds of bad outcomes, ranging from jail to death.

Floyd was born in a poor Houston neighborhood featuring crime and drugs and bad schools. He was a good athlete and went to a Florida college on scholarship, but after two years he returned to Texas, and there he traveled a path familiar to people in his neighborhood. Like 29 percent of the black males born in the U.S., he wound up in prison.

Disentangling issues of racial and economic injustice is hard. Floyd twice went to prison for possessing less than a gram of cocaine, and he was once sentenced to ten months for selling ten dollars worth of drugs. There’s no doubt that a white suburbanite is much less likely to do time for such things, but is that because police don’t stop people for driving while white or because affluent suburbanites, whatever their race, can afford good lawyers?

No doubt both. So when we look at the downstream consequences of Floyd’s first imprisonment—like the fact that it’s harder to get a good job when you’ve been convicted of a felony, and that if you don’t have a good job you’re more likely to commit another crime—we’re dealing with the consequences of both racial and economic injustice.

And when we look upstream—look at Floyd’s childhood—the two kinds of injustice are again hard to untangle. Floyd’s mother was by all accounts devoted (he had a tattoo of her nickname), and if she’d had enough money she might have moved to a more auspicious neighborhood, with better public schools, or sent her son to a private school. But she was a single mom working at a hamburger stand while taking college classes at night. No doubt Floyd encountered consequential racism while young, but no doubt this economic deprivation also took a toll. If he’d been a black kid born into a more affluent household, his chances of winding up in the criminal justice system would have been lower.

To put a finer point on it: On any given day, a black man between the ages of 27 and 32 is more than twice as likely to be in jail if he was born into a household in the bottom tenth of the income distribution for African-Americans than if he was born into a household with the median income for African-Americans. And that median income—for the entire household—is only $42,000.

In any event, Floyd’s path led to five stints in prison. He tried repeatedly, with some success, to get off drugs, but there were relapses. And the coronavirus pandemic was doubly bad news for him. He was infected with the disease, and the restaurant where he worked as a bouncer closed its doors as part of the lockdown. On the day when he famously bought cigarettes with a $20 bill that a store clerk deemed counterfeit, he was jobless and, according to the coroner, had traces of opioids and amphetamines in his system.

The disadvantages facing people born into poor neighborhoods like the one Floyd was born into are many and complex, and I’m not qualified to prescribe the multidimensional government spending the problem calls for. But to mention a few obvious policy possibilities:

(1) Improve public schools in low-income areas and provide lots of financial aid for low-income students who want to attend college or vocational school. A 2010 study found that black men who don’t finish high school are ten times as likely to have been in jail by their early 30s as black men who have finished college and three times as likely as black men who have finished high school but not college.

(2) Expand the number of low-income people eligible for free health care and improve the health care low-income people get, including robust treatment for substance abuse and other mental health problems.

(3) Create a government jobs program that, ideally, would have the side effect of improving the quality of life in low-income communities by, say, upgrading and maintaining public spaces or expanding recreational programs.

I could go on—but only after doing more research. Again, this is a complicated problem, and it’s worth not just massive government expenditure but creatively and carefully designed expenditure—a kind of Apollo project of social policy.

The Black Lives Matter protests are impressive in their energy and diversity, but when it comes to policy advocacy, they haven’t been a model of clarity and tactical savvy. “Defunding the police,” advocates say, doesn’t mean what lots of people naturally take it to mean—depriving the police of all funding. (Then why do they call it… never mind.) Rather, it means taking some police services—handling domestic disputes or the homeless, say—and moving them to other agencies, along with commensurate parts of the police budget; or maybe using a chunk of the police budget to fund some new community service.

OK, but even leaving aside what a counterproductive label “defund the police” is (polls show that blacks and whites alike react negatively to it), the underlying idea is in a certain sense too modest. It sends the message, however unintended, that new community initiatives are limited by the amount of money that can be pried away from police departments. I say think bigger!

There sometimes is bigger talk in Black Lives Matter circles—in particular about reparations. But reparations, however strong the moral case for them, will almost certainly never happen—and if they did happen, they’d probably be divisive, perhaps even making the eventual arrival of another ethno-nationalist president more likely.

This suboptimal policy agenda—consisting of things that are too ambitious, not ambitious enough, and/or self-destructively labeled—seems to be rooted in the unspoken premise that almost everything about the George Floyd tragedy is attributable either to racist policing or racism more broadly. Certainly policing needs reform, and certainly racism looms large. Even the economic disadvantage Floyd was born into is largely a product of racism. Still, if you don’t address economic disadvantage directly, as a problem in its own right, you’re leaving a lot of policy tools unused, and you’re leaving a lot of money on the table. As a practical political matter, we can direct way more resources toward victims of racism by deploying class-based policies than by relying on race-based policies alone.

Two days ago New York Times columnist Jamelle Bouie wrote a piece asserting that economic equality has long been an aspiration of the Black Lives Matter movement. He’s right—as you can see if you do a little digging on the website of Movement for Black Lives, an umbrella group encompassing BLM. But the fact that he had to remind us of this more than a month after George Floyd died is testament to how little airtime the issue of economic justice has gotten lately.

Bouie’s column cited a bygone labor slogan: “Black and White: Unite and Fight.” Exactly! Class-based policies, though by definition not about race per se, can in principle erode racism. The kinds of policies I’m advocating would naturally appeal to low-income whites, which means they’d give low-income whites and low-income blacks common political cause.

I’m not saying this would magically heal America’s racial divide. But it’s well-established that bigotry tends to grow when one group sees itself as having a zero-sum relationship with another group, and that the perception of a non-zero-sum relationship—like common policy goals, jointly pursued—can have the opposite effect.

There are black activists and politicians who are talking in non-zero-sum terms, even if cable news producers and opinion editors, for whatever reason, have spent the last month ignoring most of them. Jamal Bowman, the black former middle school principal who (pending the counting of mailed ballots) seems to have beaten incumbent Eliot Engel in a New York congressional primary, did a particularly nice riff on economic equality recently.

For three and a half years we’ve had a president who has worked to undermine the sense of interracial common cause that Bowman conveyed in that riff. Trump has tried to convince low-income whites that the Democratic party is in the thrall of identity politics and is therefore their enemy, along with its constituents. The George Floyd moment has the potential to produce powerful evidence to the contrary.

To share the above piece, use this link.

George Floyd and American foreign policy

In early June, small groups of demonstrators gathered in Israel and the West Bank to protest the killing of two men. One was George Floyd and the other was Eyad al-Hallaq, an autistic Palestinian who on May 30, while making his daily trek to a school for people with special needs, was killed by Israeli police. Protesters held signs that said #BlackLivesMatter and signs that said #PalestinianLivesMatter.

Are these two cases really comparable? Does the moral logic behind America’s Black Lives Matter protests naturally extend to a country 5,000 miles away?

Yes is just the beginning of my answer. Comparing the cases of George Floyd and Eyad al-Hallaq can be the first step toward a broad re-examination of American foreign policy. The George Floyd moment is an excellent time to ask why, in various countries, the United States routinely contributes to the killing, brutalization, and oppression of so many people—and why pretty much all those people are people of color.

It’s easy to point to differences between the cases of Floyd and al-Hallaq. Al-Hallaq, like all Palestinians living under Israeli occupation, had faced discrimination of a more formal kind than Floyd faced. He didn’t, for example, get to vote in Israeli elections, even though the Israeli government controls the Palestinian territory on which he lived.

Still, both men had been born and raised in circumstances that translated ethnicity into injustice, circumstances that tended to foster antagonistic encounters with authorities—including armed authorities who, by virtue of that ethnicity, viewed these men warily. The Israeli police who killed al-Hallaq said they’d mistaken his cell phone for a gun.

And there’s another parallel: In both the Floyd and al-Hallaq cases, the US government helps sustain those circumstances. Many Palestinians, including boys in the West Bank who gather and throw rocks at the Israeli soldiers occupying their territory, have been killed with US weapons, sometimes weapons paid for by US taxpayers. (To say nothing of the bigger pieces of US military hardware that every so often are used to kill Palestinians on a much larger scale in Gaza, which is suffocating under the pressure of an economic blockade imposed by Israel with America’s approval.)

America’s role in oppressing Palestinians goes beyond supplying Israel with arms. International attempts to condemn the building of Jewish settlements in the West Bank (which violates international law) have more than once been thwarted by America’s use of its veto in the United Nations Security Council. And thanks to an executive order issued by President Trump, American colleges that let students criticize Israel in specific harsh ways could lose federal funding.

This and the various other forms of US government support for the status quo in Israel are sometimes attributed to the “special relationship” between the two nations. And it’s true that their bond is sui generis. But America aids and abets violence and repression in other Middle Eastern countries as well.

Egypt is ruled by a US-backed dictator who in a single day killed more than 900 peaceful protesters. (They objected to his having seized power via a coup that the Obama administration insisted wasn’t a coup.) And by “US-backed dictator” I mean a dictator who is lavishly supported with American weapons and other forms of aid.

So too with Saudi Arabia’s semi-deranged crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, whose most notorious crime—having a journalist he found annoying dismembered via bonesaw in Turkey—is just the tip of the iceberg. There’s no telling how many Saudis he’s had tortured or killed. And then there are the thousands of Yemenis he’s killed—with American logistical support and often with American weapons—since 2015, when he launched one of the most ill-advised military interventions in recent history.

And then, of course, there are the cases where America has done the killing itself—most notably the Iraq invasion of 2003 and the Libya intervention of 2011.

Note that most of the victims of the above mayhem—the people who have been killed, tortured, or oppressed in the Middle East either by America or with America’s help—are people of color. Which is something they have in common with the people America continues to kill outside the Middle East, via endless aerial strikes in Somalia, Afghanistan, and elsewhere.

To be sure, in some of these cases, the brutality directed at people of color is being perpetrated by people of color. There is, for example, the Arab-on-Arab violence, done with a little help from Uncle Sam. But that doesn’t mean words like “bigotry” and “racism” have no place here. Would the average American taxpayer be so unperturbed by the carnage America sponsors if the victims were thought of as white? Or, at least, if the victims couldn’t be cast as part of an alien religion or a strange and exotic culture?

I don’t know the answer to these questions, and I don’t claim they’re easy to answer. Certainly America’s use of force isn’t always governed by ethnic or cultural affinity. Twice in the 1990s the US intervened against Christians (Bosnian Serbs in the mid-nineties and Serbs in the late-nineties) and on behalf of Muslims (Bosnians and Kosovans, respectively). But that kind of thing happens rarely, and it hasn’t happened in a while.

At a certain level of abstraction, the Black Lives Matter protests are about how America treats marginalized people, particularly people who aren’t white—how these people can be brutalized and even killed, day after day, without all this violence rising above the level of background noise until a particularly egregious instance of it goes viral.

Well, America’s foreign policy could be described much the same way. We participate in the killing, brutalization, and oppression of typically nonwhite, marginalized people, and it passes without notice except when some particularly grotesque snafu makes it newsworthy. (This time the brown people I don’t know who were killed by a missile my tax dollars paid for were at a wedding! That’s unconscionable!)

One of the admirable things about the much-derided “social justice warriors” at elite American colleges is that many of them are agitating on behalf of categories of people they don’t belong to—poor people who face incarceration, for example. So too with the Black Lives Matter protests, which have featured lots of people who will never know what it’s like to be black.

Well, American foreign policy offers an opportunity for all Americans to engage in such protest; they can protest the systemic brutalization of people in whose shoes they will never be.

PS: Rep. Barbara Lee, a peacenik of impeccable credentials, has started a movement to “defund the military”—not entirely (which even I think would be excessive!) but considerably. The activist group Win Without War has the details.

To share the above piece, use this link.

What is it like to be an electron?

In recent years more and more philosophers seem to have embraced panpsychism—the view that consciousness pervades the universe and so is present, in however simple a form, in every little speck of matter. It’s a view that’s hard to wrap your mind around, so I’m glad I got to have a conversation with Galen Strawson, a noted philosopher who is one of its most articulate proponents (and who, as a bonus, is charmingly offbeat). I interviewed Galen on the Wright Show (available on both meaningoflife.tv and as an audio podcast) more than a year ago. Below is an extended excerpt.

ROBERT WRIGHT: There’s a view that I think people are hearing more and more about called "panpsychism," and the idea there is that consciousness … pervades reality. There's some kind of consciousness over there where my curtains are—only a little tiny bit, maybe, but there's some.

And it's a view that you subscribe to, I think—but then you throw in a twist and add the word “physicalist”… So you have, I think, a pretty distinctive view. And I want to approach it by, first of all, getting clear on what you mean by "physicalism."

Now, am I right in thinking that that has come to be the term that philosophers use for what might have also been called at one time "materialism"? People hear "materialism" and they think of the idea that all there is is physical stuff, right? But now philosophers use the word "physicalism" for that. Is that right?

GALEN STRAWSON: Yes. I think it is right. I certainly use it in that way. Some philosophers mean more by physicalism than that. They tend also to mean something like "physics will tell us everything there is to tell about reality." And that's a mistake, in my view.

Yeah, I was just thinking about that today: … that science gives us everything we need to manipulate reality, but not all we need to understand reality.

Correct.

You agree?

Yes, I do. And, you know, I think of myself as a very passionate and committed naturalist. So it's not as if I have any odd agenda. I'm also an atheist, so I don't believe in any kind of god, and I don't have any sort of new age type of aspirations.

I think that I'm forced into the position I hold precisely because I wanted to have an entirely naturalistic attitude to reality.

Right. Now, a thing about physicalism is that, when you really start thinking about it, it's harder to define than you might think. … When you first hear it, you think "Well, okay—so it's all physical stuff, you could reach out and touch it, it's there, there's nothing spooky, there are no supernatural forces." But then you realize that … the deeper physics penetrates reality, the more you wonder in what sense there is physical stuff there, you know what I mean? Does that make sense?

Yes, it does, if you mean that the old picture of little tiny grainy bits of stuff—I mean, that was wiped out a hundred years ago. There aren't any such things, it seems.

Yeah, we think of atoms as these physical things, but they turn out to consist of these other things, which consist of these other things, and it's not clear that there's anything at the bottom, other than, in certain sense, math, right? ...

Well, yeah. But even there, I think you have to be careful not to have an over-substantive, over-solid picture of what that is. There just seem to be patterns in fields—like the electromagnetic field—and that's really all there is. There are no grainy little bits, even at the very bottom.

And in fact, one thing quantum physics tells us is that, once you get down to the level of the electron, things start getting pretty weird. And there are times when ... it's maybe both a particle and a wave, which seems contradictory—or it may be neither until you measure it, or maybe a probability wave until you measure it—when you get down to the smaller so-called particles, things get really weird.

Yes.

And so ... the question of whether electrons actually exist in any intuitively clear sense is kind of an open question, right?

You can read the rest of this dialogue at nonzero.org.

Activist update

Back when this newsletter was called Mindful Resistance, we created a discussion group in the Insight Timer meditation app under the same name. (The group is still there, and sporadically active, though you have to do some searching to find it.) One of the members undertook the radical initiative of organizing a group of mindful resisters that met in actual physical space—but not to discuss things, just to meditate. Well, it turns out that, lo these many years later, the group is still at it. So if you find yourself in Providence, Rhode Island, you can join a sitting on Monday or Friday at 8:30 a.m. alongside the Blackstone Boulevard running path, near Brookway Road. The group no longer posts the Mindful Resistance sign, but you shouldn’t have much trouble distinguishing them from other people in the area. They’ll be the ones sitting down with their eyes closed.

And speaking of such people: Another member of the Insight Timer discussion group recently drew our attention to a larger gathering of meditators. Sundays at 10 a.m., in Herbert Von King Park in Brooklyn, people have been gathering under the rubric “meditate for black lives.” If you want to be apprised of the group’s future events, just go here and sign up for its newsletter.

In the Times Literary Supplement, classical historian Mary Beard notes that the Romans often decapitated or replaced statues of leaders who had fallen out of favor and then offers some thoughts on dealing with controversial monuments in our time.

A bit more than a year ago, Matt Yglesias presciently wrote in Vox about what he called “the Great Awokening.” Since 2014, he observed, “white liberals have moved so far to the left on questions of race and racism that they are now, on these issues, to the left of even the typical black voter.”

As the world waits for Bibi Netanyahu to say whether Israel is going to annex parts of the West Bank (and if so which parts), critics are calling any such move the death knell for hopes of a “two-state solution” to the Israel-Palestine conflict. But in Foreign Affairs, Yousef Munayyer, executive director of the U.S. Campaign for Palestinian Rights, argues that it’s already too late for a two-state solution, and the question is what kind of one-state solution there will be.

Good news for me! Having an abysmally short attention span has its upside. In Scientific American, Holly White explains that people with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder often excel along three dimensions of creative thinking. (This piece was published last year, but I was too distracted to notice it then.)

A New York Times poll finds that Biden supporters are less likely than Trump supporters to feel proud and hopeful about America and more likely to feel anxious and angry about the state of the country—and way more likely to feel exhausted.

The Guardian lists eight of “the most stunning claims” in John Bolton’s new book The Room Where It Happened. You may not be stunned by all of them (“Trump offered favors to authoritarian leaders”) but the list is worth perusing. In the American Conservative, Barbara Slavin says the book’s account of Bolton’s approach to his job as Trump’s national security adviser is “an instruction manual for how not to do foreign policy.”

Conservative New York Times columnist Ross Douthat comes up with what, as he notes, could pass for a radical left take on the current social unrest: The Black Lives Matter protests are, in effect, being co-opted by the establishment. Because elites would be threatened by a Bernie Sandersesque class-based revolt—involving things like seriously taxing the rich and redistributing resources to the poor (as I advocate in “George Floyd, racial justice, and economic justice,” above)—the consequences of the protests are being confined largely to things like the destruction of offensive icons, the renaming of buildings, and renewed pledges for workplace diversity, especially at the elite level.

OK, that’s it! Thanks for reading. The usual entreaties apply: please share any content you feel is worth sharing, follow us (or even retweet us!) on Twitter, and consider supporting us on Patreon. And we welcome your feedback at nonzero.news@gmail.com. See you next time.

Illustrations by Nikita Petrov.

A few words on reality -- such as it may be. We evolved to perceive our surroundings and ourselves -- everything, in ways best suited to our survival. That's about the gist of it, yes? So why would we try to see beyond what we evolved to see? I mean, ok; we are curious monkeys and we love a puzzle. But if we somehow managed to see beyond what we are equipped to see I doubt it would make any sense at all to us. In fact it would likely scare the crap out of us and leave us a pile of gibbering goo. But we just can't help ourselves, can we?

I guess we would need a machine to see that other reality and display it for us -- but not being built to see that other reality, we still wouldn't see it. And so it goes. Whaddya think?

"tax the rich": there is a movement in NYC to do exactly this--that is, raise taxes on NY's 118 billionaires to fund relief for excluded immigrant workers, who pay taxes; many are essential workers. It's supported by a wide range of nearly 100 political groups, advocacy and community orgs, unions, and faith orgs, and a lot of state legislators. #FundExcludedWorkers #MakeBillionairesPay

The governor, of course, is opposed. But he's been known to respond to strong community pressure (eg, when he was moved to ban fracking in the state). So maybe...