Trump, TikTok, and America’s cognitive empathy deficit

Plus: Paul Bloom on emotional empathy and its perils

In this issue of NZN: How media coverage of Trump’s war on TikTok reflects a lack of “cognitive empathy” that (I argue) is sadly characteristic of America’s approach to the world. Also: I talk with psychologist Paul Bloom, who thinks people often deploy the other kind of empathy—“emotional empathy”—counterproductively. (And if all that doesn’t quite meet your weekly quota for empathy-related material, then be advised that on Thursday—the day this newsletter is going out—at 8 p.m. Eastern Time, I’m doing a livestream on cognitive empathy and politics with Josh Summers in memory of our mutual friend, the late Michael Brooks; details here.) Plus: Readings on the Kamala Harris foreign policy think tank, how to handle conspiracy theorists, Buddhists and racial justice, etc.

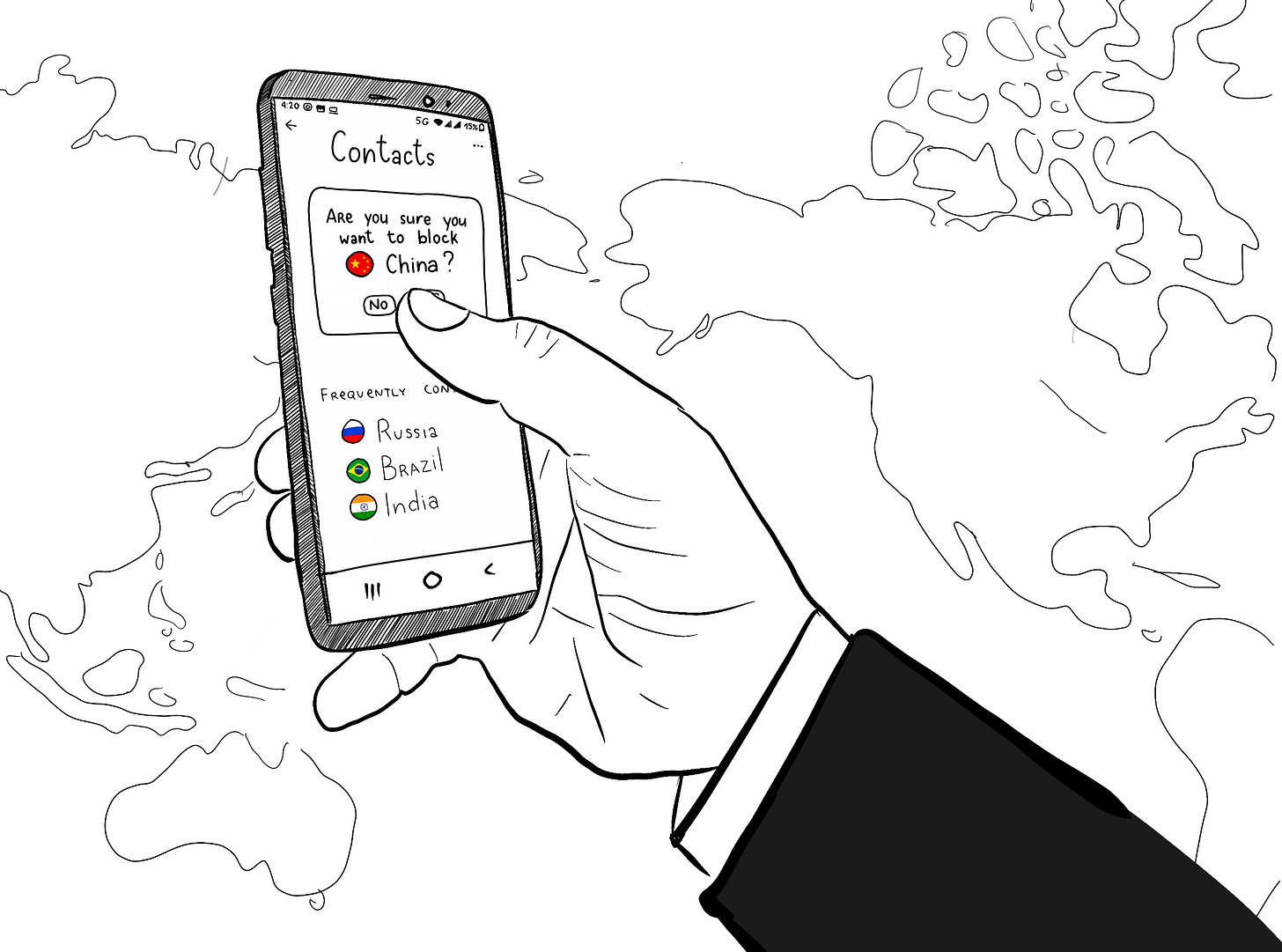

Trump’s global war on TikTok

As you may have heard, President Trump is waging thermonuclear war against a smartphone app. Last week he declared, in an executive order, that the famously zany video app TikTok represents a national emergency and will be crippled by new legal restrictions come late September—unless, he has said, it’s sold to an American company by the Chinese company that owns it.

You may have also heard that Chinese political and corporate leaders aren’t happy about this. But you probably haven’t heard that lots and lots of regular Chinese people aren’t happy about it. This is something that, so far as I can tell, the American media isn’t reporting.

In fact, to confirm my suspicion about this grassroots blowback, I had to go beyond googling and email a Chinese-American friend who for years lived in China and now follows China closely as part of his job back here in the States. He emailed back, “There's certainly a lot of popular resentment at the Trump Administration for the TikTok ban.” Many Chinese people are “livid,” he continued, “that Trump has tried to kneecap the one Chinese app to finally break through globally.”

In other words: Trump’s latest move has strengthened nationalist sentiment in China. And you know who likes to keep nationalist sentiment strong in China? Xi Jinping, the country’s authoritarian leader, whose popularity is directly proportional to it.

Kind of ironic! After all, a professed purpose of Trump’s increasingly hostile stance toward China is to weaken its authoritarian leader. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, in a landmark speech delivered last month at the Richard Nixon library, said the U.S. must “engage and empower the Chinese people” to that end. (He “stopped shy of explicitly calling for regime change,” the Wall Street Journal noted.) Yet Trump, rather than engage the Chinese people, is alienating them—and in the process has empowered the regime.

This isn’t a one-off. Various Trump tactics—the war on Huawei, restricting visas and academic exchanges, closing a supposedly spy-infested consulate, blaming China for the “China virus” and on and on—are having the same effect. “Strengthening the Chinese people’s allegiance to their authoritarian rulers is definitely a side effect of the Trump administration approach,” Gabriel Wildau, a consultant who until last year was Shanghai bureau chief for the Financial Times, told me.

Don’t waste your breath trying to explain to Trump that his policy toward China is more likely to strengthen the Communist Party’s grip on power than weaken it. Though there are people in his administration who truly want regime change in China, Trump himself is more focused on preventing regime change in America. Ever since he decided to use China as a scapegoat for his own mishandling of the pandemic, amping up tensions with China has been part of his re-election strategy. And it has only become a more integral part as he has discovered the many ways the perfidious “Beijing Biden” can be woven into an anti-China narrative.

Meanwhile, the administration’s more ardent China hawks are seizing this political moment to sever sinews of engagement with China that were decades in the making. The result of all this is massive momentum toward a new Cold War that could last decades and impede desperately needed international cooperation on multiple fronts, ranging from climate change and other environmental challenges to various kinds of arms control challenges (weapons in space, bioweapons, cyberweapons, etc.).

This slide toward planetary crisis will be hard to stop. But one way to slow it would be for the American media to depart from its long tradition of doing a pretty bad job of reporting on how people in other countries see the world. If more Americans knew that Trump’s policies are systematically energizing, and probably expanding, Xi Jinping’s grassroots base, these policies might become at least a bit less politically profitable.

To put it more clinically: The American press, along with the American people, needs to do a better job of balancing two kinds of empathy: emotional empathy and cognitive empathy.

Emotional empathy is the kind of empathy you’re probably familiar with: identifying with the emotions of others—“feeling their pain,” for example. It’s also the kind of empathy that already plays a pretty big role in American foreign policy discourse.

The plight of the Uighur Muslims in China’s Xinjiang province, for example, has evoked a fair amount of emotional empathy. And rightly so. Though the contours of their persecution aren’t entirely clear—how many of them have been sent through what the Chinese government euphemistically calls “education camps,” what exactly happens there, and what happens to them when they leave—it may not be an exaggeration to say, as some have said, that the government is conducting “cultural genocide.” (Satellite images seem to show whole mosques disappearing.)

But this emotional empathy—sensing and even in some measure sharing in people’s suffering—doesn’t by itself enable you to reduce the suffering. That takes skill, and skill requires the second kind of empathy: cognitive empathy, which just means understanding how people view the world, whether or not you identify with their emotions. If we don’t apply cognitive empathy to the major players in China—political leaders, other elites, and the Chinese people—we’re unlikely to understand the political and cultural situation there well enough to help the Uighurs, pro-Democracy protestors in Hong Kong, or anyone else.

If a failure to understand how people abroad view the world helps usher in a new Cold War, that won’t be the only catastrophic war of this century grounded in such a failure. In 2003, on the eve of the invasion of Iraq, Vice President Dick Cheney predicted that American troops would be “greeted as liberators.” And some Iraqis did greet them as liberators! But lots of Iraqis didn’t, and many of them had guns.

Cheney’s generic misconception was one that to this day is widely held by lots of Americans, including a disconcerting number of journalists. In this view, authoritarian countries consist of two parts: (1) oppressive authoritarian regime; (2) oppressed people, who hate their autocratic rulers and spend their waking hours longing for liberation.

In truth, authoritarian countries are kind of like non-authoritarian countries: some people see themselves as benefiting from the leader’s policies, and view the leader favorably, and some people don’t. When a country’s leaders, like China’s, have led the country on a four-decade march toward the status of global superpower—and in the process have radically elevated living standards in the bottom half of the income distribution—there will probably be a fair number of people in that first camp. Dealing with an emerging superpower without understanding basic facts like this can lead to a world of trouble.

Understanding these facts won’t bring miracle cures. Once you see the breadth of the regime’s support, you realize that anyone who wants to fundamentally improve human rights in China—in Hong Kong or Xinjiang or anywhere else—will probably have to play a long game.

My own view is that part of that game should be preserving engagement with China, for two reasons. First, as I’ve said, we can’t afford to wait for a decades-long Cold War to pass before addressing threats to the planet that in some cases are truly existential. Second, I think we have a better chance of nudging China toward progress on human rights in a context of engagement than in a context of belligerent disengagement.

And I emphasize the word “nudging.” We have to recognize the practical limits on our ability to reshape the world’s nations in our image. To say nothing of recognizing why, in the eyes of those nations, our image may not be as impressive as it seems to us, and our history may not look like an untarnished credential for moralizing. If you need help with this particular exercise in cognitive empathy, google “Japanese-American internment” or “Jim Crow laws”—or, to bring it up to the present moment, “national incarceration rates,” a metric that allows Americans to chant without fear of contradiction, “We’re number one!”

None of this means never playing hardball with China. Though some of Trump’s get-tough policies are transparent attempts to capriciously wreak havoc on Chinese companies (the war on Huawei smartphones, for example), some of them rest on security concerns that are at least remotely plausible (like the question of whether Huawei should build our 5G network). Even concerns about TikTok aren’t totally groundless (some of the app’s past data-gathering practices do warrant scrutiny)—though Trump’s thuggish approach to the issue is, among other things, embarrassing. (He’s even said the US government should get a commission on any sale of TikTok to an American company, since his executive order will have coerced TikTok’s owner into selling!)

So too in the realm of economics: Our trade policies have paid too much attention to corporate profits and not enough to American workers or to respect for intellectual property. Raising these issues with China in a tough and coherent way is good policy.

But coherence is not a word you can apply to Trump’s China policy—unless, maybe, you see it as a coherent attempt to get him re-elected, or a coherent attempt to fracture the world.

A humane and effective foreign policy would draw on both emotional and cognitive empathy, with the former helping us set goals and the latter helping us reach them. America has probably never managed to deploy these two resources optimally, but it’s rarely been as far from that ideal as now.

To share the above piece, use this link.

Paul Bloom is not a monster! I don’t normally begin my introductions of people with those kinds of reassurances, but Paul, a professor of psychology at Yale, is the author of a book called Against Empathy—and that title has led to some misunderstandings. Paul would like you to know that he isn’t entirely against empathy; he’s just against its counterproductive application—which he thinks is pretty common. After his book came out in 2016, I had a conversation with him on The Wright Show. I always have fun talking to Paul, and I think this extended excerpt shows why.

PAUL BLOOM: ...I actually suffer from an abundance of empathy. This book is, in some sense, a self-help book for myself. I tear up at things, I get really upset when I hear stories about people suffering. My charitable contributions are bizarre, based on personal prejudices and strong feelings.

ROBERT WRIGHT: So this book is a cry for help.

This is definitely a cry for help.

I would think that the temptation, if you write a book called Against Empathy, when you meet someone who has only heard the title… is to say, "No, don't get the wrong idea."… And the subtitle kind of says it: "The case for rational compassion."

Exactly. The subtitle is saying: “Look, I'm against something, but this is not one of those weird pro-psychopathy books that [says] we should be cruel to each other. It's not some sort of a plea for selfishness or brutality. It's rather: if you want to be a good person, there's a better way to do it.” ...

Some people think "empathy" is just a catch-all term for everything good: being kind, being moral, being compassionate or understanding. I have no problem if people want to use the word that way, and in that case, I'm not against empathy. I mean it in a more narrow sense: roughly, putting yourself in the shoes of other people, feeling their pain, feeling their suffering.

And even taking that into account, I'm not against empathy for all realms of life. I think it's a wonderful source of pleasure. But the argument I make, which still remains somewhat controversial, is that this narrow type of empathy is a very bad moral guide. It makes us into worse people, it makes the world worse.

I think later we'll get into some of these distinctions: between empathy and compassion, and also a distinction you make between emotional empathy—you know, feeling their pain—and cognitive empathy, [which is] just understanding what the world looks like to them—that you're not railing against... Why don't you give us some examples of the damage empathy can do.

So, I give two examples.

You can read the rest of this dialogue at nonzero.org.

A piece in the newsletter BNet makes the case that, “Being skeptical of TikTok is not weird. Being skeptical of TikTok to a far larger degree than any other Big Tech company is absolutely weird.”

Wondering what kind of influence Kamala Harris might exert on foreign policy in a Biden administration? In October of last year, in the lefty periodical In These Times, Branko Marcetic profiled the Center for a New American Security, the think tank that was channeling its influence on the presidential campaign largely “through the campaign of Sen. Kamala Harris, who has drawn heavily from its ranks to fill her line-up of foreign policy advisors.”

In Tricycle, Ann Gleig, author of American Dharma: Buddhism Beyond Modernity, looks at the historical relationship between Buddhists and racial justice.

In FiveThirtyEight, Likhitha Butchireddygari recently looked at the polling on American attitudes toward China over the last fifteen years. Plot spoiler: we’re at a Sinophilic low point. But Butchireddygari explains why these sentiments may not give Trump much help in the 2020 election.

In MIT’s Technology Review, Tanya Basu offers some advice on how to change the minds of conspiracy theory believers in your life.

On The Wright Show, I recently had conversations with two DC foreign policy thinkers—Heather Hurlburt, a self-described “pragmatic liberal internationalist,” and Emma Ashford, a “realist”—about what paradigm should guide America’s engagement with the world. Plus, I’m now doing a weekly show with my old friend and ideological nemesis (He voted for Trump!) Mickey Kaus. Audio versions of all these conversations are available on The Wright Show podcast feed.

OK, that’s it! Don’t forget that you can follow us on Twitter— @NonzeroNews –and can send us any praise or chastisement you may have: nonzero.news@gmail.com. See you next time.

Illustrations by Nikita Petrov.