Introducing the progressive realism report card

Our first student: Biden foreign policy adviser Tony Blinken.

Remember last Saturday? When the networks declared Joe Biden the president-elect, and it was possible, for one bright shining moment, to imagine that Donald Trump would respond to news of his imminent departure from the White House by preparing to depart from the White House?

Now, a week later, there is so much worry about Trump refusing to leave that people are semi-seriously talking about how a skilled hostage negotiator would handle the situation. But here at the Nonzero Newsletter we’re choosing to optimistically assume a happy ending to this crisis and focus our worry elsewhere. Namely: on the question of whether, after Trump is finally extracted from the oval office, its new occupant will be much of an improvement over him in the foreign policy department.

Today we launch a series of evaluations of people who are in the running for major roles on Biden’s foreign policy team. We call these evaluations “progressive realism report cards”—which raises two questions:

1) Why progressive realism? For starters, because that is this newsletter’s unofficial foreign policy ideology. (I described its essence concisely in a 2016 piece in The Nation and, less concisely, in the 2006 New York Times essay in which I coined the term.) But also because progressive realism stands in such stark contrast to the ideology of “the Blob”—the bipartisan foreign policy establishment that has long managed to retain power in Washington notwithstanding its demonstrated tendency to screw up the world.

To put a finer point on it: I think that if progressive realist principles had guided America’s foreign policy since the end of the Cold War, Donald Trump wouldn’t have been able to get the political traction he got in 2016 by promising to extricate American troops from the various messes we’ve gotten them into. Because, by and large, the messes wouldn’t exist.

2) Why report cards? Do I honestly think that the people we give low grades will be assigned commensurately low-status positions (or none at all) in the Biden administration? No, for two reasons: (1) the Washington establishment seems to work the other way around: the worse your record on foreign policy, and the more damage your ideas have wreaked on the world, the more influence over policy you are granted; (2) we’re just a little newsletter, not a big and influential platform.

However, if enough like-minded, public spirited readers share these report cards on Twitter or Facebook, maybe we’ll be able to punch above our weight! And maybe, eventually, thanks to efforts at this newsletter and like-minded renegade outlets, the foreign policy establishment will start to feel the heat. (A guy can dream…)

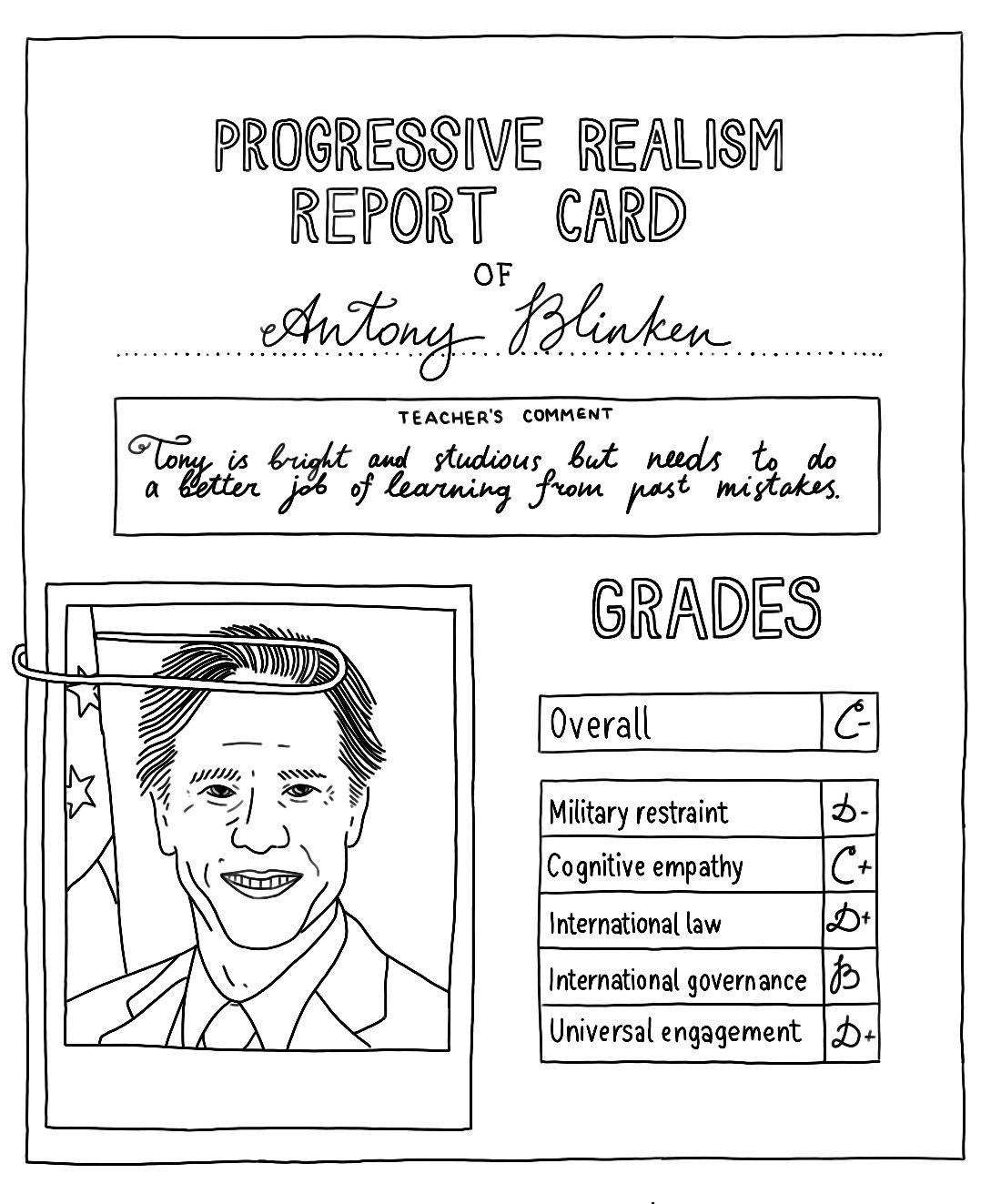

Below is our first report card. It’s for Tony Blinken, who is probably Biden’s closest foreign policy aide and will almost certainly wind up with great influence in the new administration. Immediately below the report card itself is the heart of the matter—our justification for each of the grades Blinken received. (If you want to read a subject-by-subject explanation of the grading criteria—which doubles as a short introduction to progressive realism—that’s here.) In the coming weeks we’ll issue report cards to other prospective Biden foreign policy advisers—some of whom, we’re happy to report, will get higher grades than Blinken.

To share the above piece use this link.

Grading Biden’s Foreign Policy Team: Tony Blinken

Background: Blinken is a liberal interventionist with an emphatic idealism about the virtues of “American leadership.” His relationship to Biden goes back decades, and he is considered a favorite for national security adviser or secretary of state.

Military restraint (D-)

Blinken was a key adviser to Biden when the senator voted to authorize the use of force against Iraq. Blinken has tried to recast the vote as merely “a vote for tough diplomacy,” but post-invasion remarks by Biden make that claim implausible. In a recent Washington Post op-ed that Blinken co-authored with Robert Kagan, one of the chief architects of neoconservative foreign policy doctrine, he implied that the problem with the Iraq War was poor execution (“bad intelligence, misguided strategy and inadequate planning for the day after”) rather than the very idea of invading a country in violation of international law even after it had admitted weapons inspectors to assess the claims motivating the invasion.

Nor does Blinken have second thoughts about the US and its allies having flooded Syria with weapons that turned a doomed insurrection into a raging but futile civil war, leading to countless deaths and creating countless refugees (a policy that, as an Obama administration staffer, he played an important role in shaping). Blinken says, along with Kagan, that the problem with our Syria policy was that we didn’t deploy even more force (in what, remember, was an explicit attempt to depose the government of a sovereign nation). Blinken and Kagan also express opposition to withdrawing US troops from Syria.

Cognitive empathy (C+)

Blinken’s capacity to understand the perspective and motivations of world leaders sometimes seems deficient. His judgment that North Korean leader Kim Jong-un “at best acts impulsively, and maybe even irrationally” evinces, in the view of Asia security specialist Denny Roy, “a disappointingly shallow understanding of North Korea.” The casual attribution of irrationality to foreign leaders often generates popular fear that can lead to war, and it often raises the question that Blinken’s version of it raises here: If the leader in question is so irrational, how has he managed to stay in power notwithstanding various steep challenges (including, in Kim’s case, the facts that (1) his impoverished people have every reason to dislike him; (2) he inherited leadership at a young age, amid skepticism and even resistance from within North Korea’s political establishment; and (3) various powerful nations would love to see him deposed)?

When the subject turns to Russia, Blinken’s cognitive empathy record is mixed. On the one hand, he accepts that such American actions as NATO expansion made Vladimir Putin feel threatened, which shows some understanding of Russian interests in its “near abroad.” But his defense of NATO expansion attributes to Putin an indifference to risk that is inconsistent with Putin’s record. “I think it’s a good thing that we expanded NATO,” Blinken has said. “I ask myself, where would the Baltic states be right now if they were not in NATO? Where would Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic be?” The suggestion that Russia would have rolled tanks into Warsaw if Poland hadn’t joined NATO strains credulity. The closest real-world analogy, Putin’s seizing of Crimea, involved a region that had been part not just of the Soviet Union but, until the 1950s, of the Russian republic—and a region whose mainly Russian-speaking populace by and large supported the return of Russian rule.

Blinken gets points for recognizing that Russia felt betrayed by America’s 2011 Libya intervention (which morphed from a humanitarian mission authorized by the UN Security Council with Russian acquiescence into an unabashed regime change operation). And he sees that this complicated prospects for the Obama administration’s attempted “reset” of relations with Russia. Still, he seems reluctant to contemplate the possibility that this and other perceived American affronts were critical in the subsequent souring of US-Russia relations, preferring to cast Putin’s disposition as the determining factor. “Mr. Putin started with or developed a very zero-sum view of the relationship,” he said in a PBS interview. “That's really the defining problem today.”

Respect for international law (D+)

Blinken supports applying international law to adversaries, but he has little time for legal strictures when they could constrain American behavior. So, on the one hand, he heaped praise on Trump’s advisers for their moral and legal clarity about Russia’s invasion of Crimea. (“It is not acceptable for one country to change the borders of another by force... It is not all right for Russia to decide Ukraine’s future.”) But his respect for universal rules seems to have deserted him during the invasion of Iraq (which then–Secretary General of the UN Kofi Annan has deemed illegal). So too with the arming of Syrian rebels and the subsequent placement of American troops in Syria against the wishes of its government—both highly dubious under international law and both fine by Blinken’s lights.

Blinken once cited George H.W. Bush’s invasion of Panama and subsequent extradition of its president, Manuel Noriega, as a judicious use of force. Invading a country in order to arrest its leader is, at best, problematic under international law, as a legal scholar noted in the Christian Science Monitor at the time.

Support for international governance (B)

Blinken supports various useful international agreements and institutions in realms such as arms control and the environment, and he helped then–Vice President Biden get India on board with the Paris Climate Agreement. He has also advocated using trade deals like the Trans-Pacific Partnership to fight climate change and improve labor conditions. And, while in the Obama administration, Blinken helped negotiate multilateral agreements, most notably the Iran nuclear deal, which set a new standard for arms control verification and defused a source of Middle East tension.

However, Trump abandoned that deal, and now, amid hopes that it could be revived in a Biden administration, comments made recently by Blinken are not encouraging. In abandoning the deal, Trump not only reimposed sanctions that had been dropped as part of the deal—he added new “maximum pressure” sanctions that have inflicted additional suffering on the Iranian people and have shown no signs of altering Iranian policy. In an interview with Jewish Insider, Blinken said that a Biden administration, even if it suspended the nuclear-related sanctions as part of a return to the deal, would “continue non-nuclear sanctions as a strong hedge against Iranian misbehavior in other areas.” The apparent assumption here is that Iran wouldn’t insist on a return to the status quo ante—including freedom from Trump’s “maximum pressure” sanctions—as part of reentering a deal that it had been fully complying with when America reneged on it. Even leaving aside the question of whether Iranian politics do permit a return to the deal under humiliating conditions, shouldn’t Biden want to uphold the idea that America stands by its word and sticks to the original terms of its deals, notwithstanding the unfortunate aberration of the Trump era?

One ray of hope: In an earlier interview Blinken sounded more open to restoring the status quo ante, with the elimination of all Trump-era sanctions. But one additional source of worry: In the Jewish Insider interview, Blinken declined to rule out the possibility that Biden would demand additional concessions from Iran, unrelated to the nuclear deal, in exchange for reviving the deal. This moving of the goalposts has long been favored by neoconservatives and other hardliners who opposed the original Obama nuclear deal.

Support for universal engagement (D+)

On the positive side, Blinken rejects the idea of “decoupling” the American and Chinese economies. But Blinken’s worldview sometimes evinces a bit of the Manichaeism that can create or deepen global economic and diplomatic fissures—a real concern at a time when some observers fear the onset of a “new Cold War.” He casts the world as a battle “between techno-democracies on the one hand, and techno-autocracies, like China, on the other hand.” He has advocated a “league of democracies” that would strengthen “military security” and “forge a common strategic, economic, and political vision.” The world’s democracies, he says, could develop “a road map for countering challenges, whether it’s coming from Russia, or China in different ways, or Iran.”

At a time when so many problems—environmental problems, arms control problems, and more—call for broad international collaboration, does it really make sense to focus your bridge-building efforts on the countries most like yours—countries you tend to get along with pretty well anyway? Especially when those efforts, by their nature, could exacerbate tensions between you and countries you don’t naturally get along with?

Miscellaneous: In 2017, after leaving the Obama administration, Blinken co-founded a consulting firm with Michèle Flournoy (a leading candidate for secretary of defense) called WestExec Advisors, which refuses to disclose its clients but has said that some are in the defense industry. Blinken began a leave of absence from WestExec in August, and he could, by severing ties to the firm, technically avoid conflict of interest issues while serving in a Biden administration. Still, his robust participation in the “revolving door” culture of the military–industrial complex raises questions about his ability to focus steadfastly on the national interest.

Overall grade: C-

—Robert Wright and Connor Echols

To share the above piece use this link.

In Current Affairs, Nathan J. Robinson argues that the time to start worrying about Trump's post-presidential resurgence is now. (And, yes, as the piece’s epigraph reminds us, the New York Times actually did run a “Hitler Virtually Eliminated” headline—albeit a small one—on the front page in 1923.)

After the terrorist beheading of a French teacher who showed students cartoons of the prophet Muhammad, French President Emmanuel Macron called for a more French, secularized version of Islam and was greeted by criticism and protests in numerous Muslim-majority countries. In Bloomberg Opinion, Pankaj Mishra contends that Macron’s discourse about the “right to offend” Muslim people hurts prospects for harmony between his country’s “secular” (historically Christian) majority and its Muslim minority. “It is one thing to defend freedom of expression—an obligation of all democratic leaders,” Mishra writes. “It is quite another to deploy a whole nation behind a particular expression of that freedom.”

Elixir for tribalism: America is divided in many ways, but in every state where the legalization or decriminalization of drugs was on the ballot, it won, notes Vox.

In Responsible Statecraft, Anatol Lieven argues that a lack of (cognitive) empathy has led American foreign policy astray. He laments our failure to understand Russian interests, even when they parallel our own. In Syria, for example, Russia has supported a dictator in order to avoid a power vacuum—much as we once did in Algeria and currently do in Egypt. Lieven leaves us with advice on how to deal with Washington’s new bogeyman: “We had better hope that in dealing with the vastly more formidable challenge of China our policy elites will engage in real study, eschew self-righteousness, and identify and not attack the vital interests of China, as long as Beijing does not seek to attack our own.”

A video on the philosophy of Thomas Metzinger offers reasons to think that the “self” may not exist. (I interviewed Metzinger in 2018 on my podcast, The Wright Show.)

In Vox, Umair Irfan assesses Pfizer's Covid vaccine, explaining what 90 percent efficacy actually means, how the drug company's approach to developing the vaccine works, and why it may take a while for the vaccine to get to market.

In Commonweal, Jesuit Scholastic Fernando C. Saldivar makes the case that the U.S. should join the E.U. and China in ratifying the Arms Trade Treaty, which bans the export of weapons that could be used to commit atrocities. The priest-in-training condemns the current, unregulated system, which gives arms dealers “a highly lucrative freedom to look the other way while the Saudis target noncombatants” in Yemen. “We can no longer pretend not to know—or appear not to care—what is being done with bombs and missiles made in America,” Saldivar writes.

A thought experiment about utilitarianism raises the oft-overlooked question of whether maybe you should let an AI eat you.

OK, that’s it! Don’t forget to follow us on Twitter, send us heartfelt missives (nonzero.news@gmail.com), and share anything in this newsletter you consider worth sharing. Thanks.

Illustrations by Nikita Petrov.

Kind of disturbing his record on International Law. Thank you for this newsletter. I was referred by Peter Beinart