Could William Burns save Biden’s foreign policy?

Plus: Sharon Salzberg on how mindfulness came to America

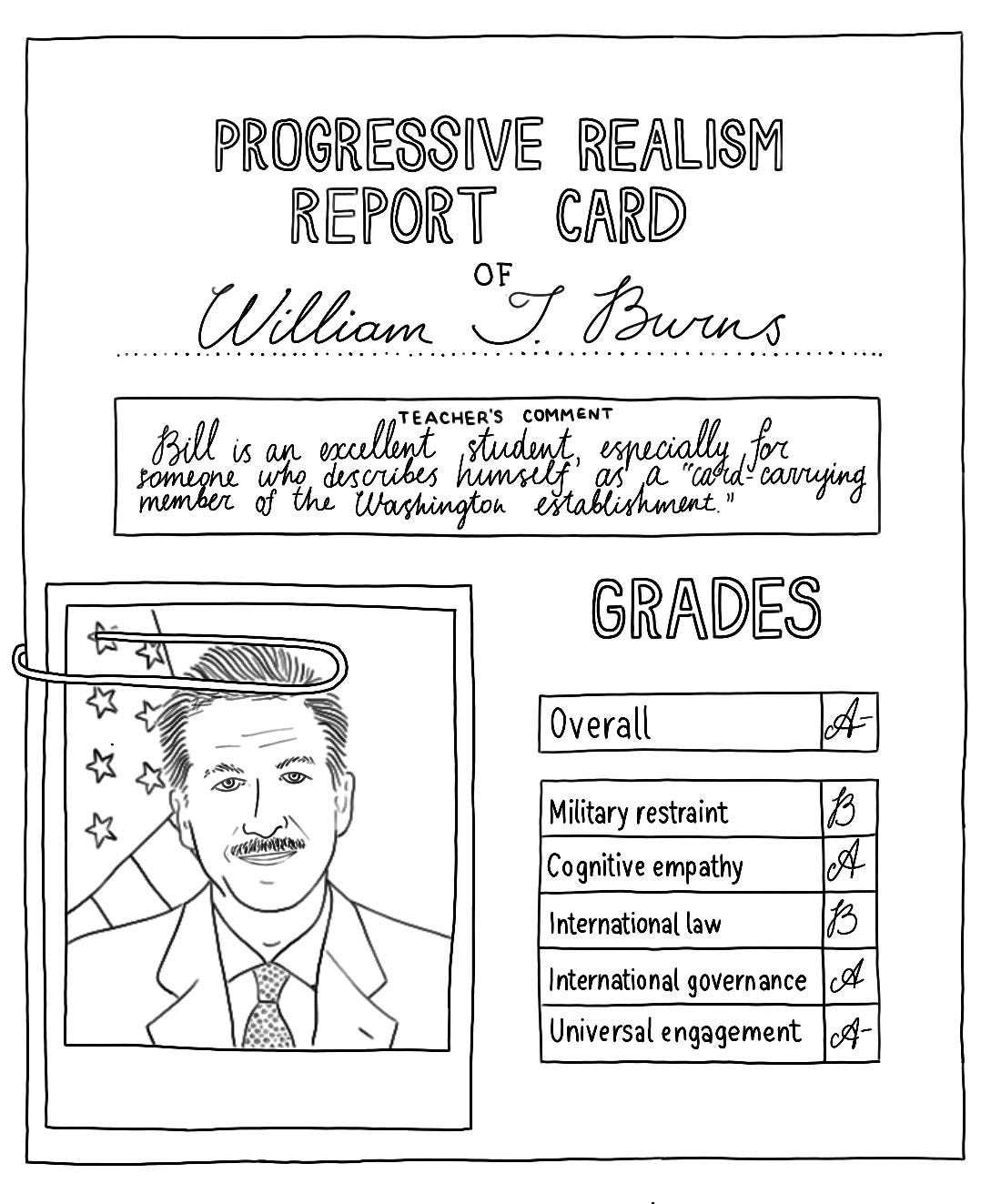

In the previous issue of NZN we unveiled the progressive realism report card—a way of evaluating candidates for the Biden administration’s foreign policy team. We issued the first report card to longtime Biden adviser Tony Blinken, who was judged a C- student (and who evinced such diplomatic skill in his response to this grade that we were briefly tempted to raise it to C ). This week’s report card is for William Burns, much-mentioned as a candidate for secretary of state. Burns hasn’t entirely escaped the influence of the dreaded Blob (aka the foreign policy establishment), but he’s probably the closest thing to a progressive realist in the running for that critical state department position. So check out our assessment of Burns below. And below that, you can check out my conversation with Sharon Salzberg about how she and a couple of other seminal American Buddhists (Joseph Goldstein and Jack Kornfield) helped bring mindfulness practice to America in the 1970s. And at the very bottom of the newsletter, as usual, are some readings.

Grading candidates for Biden’s foreign policy team: William Burns

Background: Burns, a career diplomat who has served as ambassador to Russia and as deputy secretary of state, gets particularly high marks for cognitive empathy—understanding the perspectives and motivations of international actors.

For our grading criteria, click here.

Military restraint (B)

Few if any contenders for foreign policy positions in the Biden administration surpass Burns when it comes to appreciating one tenet of progressive realism: military interventions have a way of leading to bad things. In a ten-page memo Burns wrote to Secretary of State Colin Powell, then his boss, during the runup to the Iraq War, he laid out a cornucopia of possible unintended consequences, including some that became all too real. (Like: Iran feels threatened and acts accordingly.)

Even highly surgical uses of violence, Burns recognizes, can have blowback. Last year he wrote that, during the Obama administration, as “drone strikes and special operations grew exponentially,” they were “often highly successful in narrow military terms” but at the cost of “complicating political relationships and inadvertently causing civilian casualties and fueling terrorist recruitment.”

So it’s not surprising that Burns has often pushed for non-military solutions to foreign policy problems. Still, he has supported dubious interventions—such as America’s joining allies in arming Syrian rebels, a policy hatched while Burns was deputy secretary of state in the Obama administration.

In retrospect, it’s not shocking that this policy only succeeded in amplifying the killing and chaos, given the conflicting agendas of our allies and the divergent aims of the various rebel groups—not to mention the aforementioned inherent unpredictability of military action. Yet, even with years of hindsight, Burns confined his criticism of this proxy intervention to matters of timing and execution. In his 2019 book The Back Channel, he said we should have given more aid to the rebels earlier. But Burns does, at least, get credit for considering Obama’s public demand for regime change (“Assad must go”) unwise, and for having initially hoped for more open-ended negotiations than that demand permitted.

Cognitive empathy (A)

Burns is adept at seeing the perspectives of international actors, as demonstrated in particular by his views on Russia. He has a history of dealing effectively with the country, and he takes Moscow’s interests seriously. Unlike many in the foreign policy establishment, Burns doubts the wisdom of NATO expansion—including its early phases but especially its later ones. When the US “pushed open the door for formal NATO membership for Ukraine and Georgia,” he has said, “I think that fed Putin’s narrative that the United States was out to keep Russia down, to undermine Russia and what he saw to be its entitlement, its sphere of influence.”

Burns believes that, though Putin clearly sees the US as an adversary, he doesn’t see the US-Russia relationship in purely zero-sum terms; Putin is capable of seeing “those few areas where we might be able to work together. He is capable of juggling apparent contradictions.”

Burns is very aware—as many US officials over the years have not been—that hectoring foreign countries about how they should behave can be counterproductive. “I’ve always felt we get a lot further in the world with the power of our example than we do with the power of our preaching,” he said in a New Yorker interview. “Americans can sometimes... be awfully patronizing overseas.”

Respect for international law (B)

Burns is generally a strong advocate of international law. And in the course of his career he has often had occasion to invoke it—as when, in 2014, he said disputes over islands in the South China Sea should be resolved via adjudicatory mechanisms outlined in the Law of the Sea Convention. (Had he not been speaking for the US government, he might have added that, regrettably, America itself has not ratified that convention.)

Unfortunately, Burns seems to have adopted the habit, widespread in the foreign policy establishment, of being more fastidious in applying international law to adversaries than to the US. In The Back Channel he offers some practical criticisms of America’s 2011 intervention in Libya, but he doesn’t note that when the mission shifted from defending imperiled civilian populations to overthrowing the regime, it arguably violated the letter of the authorizing UN resolution and certainly violated its spirit. Similarly, his discussion in that book of Obama’s arming of Syrian rebels evinces no concern about the fact that this intervention, according to common legal reckoning, violated the UN Charter.

Support for international governance (A)

Burns certainly supports international governance of a progressive sort—agreements and institutions that address climate change and arms control, for example, and the inclusion of labor and environmental provisions in trade agreements. And he has been deeply involved in multilateral problem solving, such as the Iran nuclear deal.

But what sets Burns apart from your typical progressive supporter of international governance is his understanding of the need to expand it beyond these traditional areas. He recognizes, for example, that if work in artificial intelligence and genetic engineering proceeds without restraint in a context of intense international competition, bad things could happen. So he wants to “create workable international rules of the road” in these areas, and he wants the US State Department to “take the lead—just as it did during the nuclear age—building legal and normative frameworks.”

Universal engagement (A-)

As a quintessential diplomat, Burns believes that the U.S. should be open to relations with any country willing to talk. He is especially emphatic about the importance of maintaining diplomatic and economic engagement with China; he criticizes those who “assume too much about the feasibility of decoupling and containment—and about the inevitability of confrontation. Our tendency, as it was during the height of the Cold War, is to overhype the threat, over-prove our hawkish bona fides, over-militarize our approach, and reduce the political and diplomatic space required to manage great-power competition.” And Burns recognizes one of the biggest payoffs of engagement with China: to “preserve space for cooperation on global challenges.”

Burns eschews a Cold War not just with China but with authoritarian states more broadly. He is refreshingly skeptical of proposals—fashionable in neoconservative and some liberal circles—to form a “league” or “concert” of democracies that would fight “techno-authoritarianism.”

Burns doesn’t seem to have expressed the degree of skepticism about America’s promiscuous use of economic sanctions that a progressive realist might like. But he gets points for at least recognizing the inconsistency of their application. “We focus our criticism on Maduro, in Venezuela, who richly deserves it, and then pull punches with Mohammed bin Salman, in Saudi Arabia,” he said in a New Yorker interview.

Burns also recognizes that the foreign policy establishment’s obsession with Iran is, well, obsessive. Tehran has “an outsized hold on our imagination,” he says. Yes, he believes, Iran poses threats to American friends and interests, but those threats are manageable, in part because, contrary to a common American view, Iran is “not 10 feet tall.”

Miscellaneous

(1) After leaving the government, Burns became president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. That’s a highly and rightly respected position. But it should be noted—since any good progressive realist wants to root out the influence of the military industrial complex—that Carnegie has taken money from Northrup Grumman (as well as from such foreign countries as Taiwan and the United Arab Emirates and from NATO).

(2) Burns deserves credit for seeing that the foreign policy establishment, confronted by Trump’s jarringly disruptive policies, is in danger of mindlessly retreating to pre-Trump policies that in fact need sharp revision. Recounting (and embracing) the bipartisan opposition to Trump’s abrupt withdrawal of military support for Kurds in Syria, he adds, “If all this episode engenders, however, is a bipartisan dip in the warm waters of self-righteous criticism, it will be a tragedy… We have to come to grips with the deeper and more consequential betrayal of common sense—the notion that the only antidote to Trump’s fumbling attempts to disentangle the United States from the region is a retreat to the magical thinking that has animated so much of America’s moment in the Middle East since the end of the Cold War.” This magical thinking, he continues, involves “the persistent tendency to assume too much about our influence and too little about the obstacles in our path and the agency of other actors.”

Overall grade: A-

To share the above piece, click here.

Bringing insight meditation to America

I was lucky enough to do my first meditation retreat—back in 2003—at a landmark of American Buddhism: the Insight Meditation Society in Massachusetts. As much as any institution, IMS was responsible for bringing to America a kind of meditation known as vipassana—which is usually translated as “insight” and can be thought of, for practical purposes, as roughly the same thing as mindfulness. I was also lucky to have already met, at this point, two of IMS’s co-founders—Joseph Goldstein (who has previously appeared in the newsletter) and Sharon Salzberg, who is now world-famous for her teachings not only on mindfulness but also on lovingkindness meditation. Recently I had a conversation on The Wright Show podcast with Sharon about her latest book, Real Change, and we wound up talking both about the book and about the 1970s, when she and Joseph and Jack Kornfield co-founded IMS after sojourns in Asia.

BOB: I'm so glad I'm going to get to talk to you. We're old friends, for one thing. But also, you've got a new book out. It's the latest in a series of Real books. You've written a book called Real Happiness, you've written a book called Real Love, and this book is called Real Change.

SHARON: That's right. I somehow got on the Real train. I don't know how that happened. People are teasing me, like "maybe your next book is Real Life."

Or, you could fool them and just go with a series of Fake books. Fake Change. Fake Love. Fake Happiness. Actually, we're all pretty good at fake happiness already. You don't need to write that one.

You’re very well known in the American Buddhist community. You co-founded a very important institution, the Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Massachusetts, which I would say is asresponsible as any institution for bringing mindfulness meditation to the attention of the American public.

I mean, there had been waves of Buddhism. The first was Zen in California, then Tibetan in Colorado. Neither of those is so associated with mindfulness per se as the Theravada (and, specifically, Vipassana) tradition that you brought in.

Yeah, I think that's fair to say. We started IMS on Valentine's Day of 1976. Joseph Goldstein and I (who had met in India) had been back for a couple of years teaching. Jack Kornfield was having a parallel life in Thailand while we were in India, and he was also back. And the three of us, and some other friends, would just teach in these different cohorts as an invitation came in. And somebody suggested to us, "Why don't you start a center?"

We were young and naive. I was 23 years old. I'm not sure I knew what a mortgage was in those days. And we said, "Sure." I thought we could get a mortgage. We had three friends who went to the bank, and personally got out loans so that we could open up.

Is that right, couldn't get a mortgage?

Couldn't get a mortgage.

They were bad judges of potential, I would say. So you'd been to India at a very young age. I think you were what, 18?

I was 18, yeah.

18 when you went to India. As one did in those days, I guess, if one was looking for a certain kind of thing.

Your book is called Real Change—the subtitle is Mindfulness to Heal Ourselves and the World. I think some people think of meditators as people who aren't really out to change the world, and in fact there's people who are using meditation to kind of insulate themselves from the world.

I wanted to start out by asking: What was the spirit of the times in the 70s? I mean, there was very much a sense that it was time to change the world. You would've been in India in the early 70s, is that right?

Yeah, I left in 1970.

So yeah, that's like, you know, hippie city, and everyone wants to change the world. Was the idea explicit that, if you were going East to seek wisdom and learn about meditation and contemplative traditions, that was part of transforming the world?

Well, first, I just want to say that I was actually at Woodstock. If we're talking about hippies, I have some authenticity I can lay claim to!

That's impressive! Let me ask a Woodstock question. Is it true that it looks better in retrospect than it felt at the time? I mean, there was a lot of rain and stuff, right?

You can read the rest of this dialogue at nonzero.org.

A lament in The Beinart Notebook—a new newsletter put out by my old friend Peter Beinart—notes that Joe Biden is unlikely to pursue a very progressive foreign policy and that “American progressives haven’t mobilized to change foreign policy in the way they have on domestic policy.” If you want to help improve that situation, you should subscribe to Peter’s newsletter (while, I might suggest, continuing to read this one).

Adapting to changes our species has inflicted on Earth’s environment is possible! At least, it’s possible for species other than ours. A flower called Fritillaria delavayi, which grows on rocky mountains in China, has long been used in traditional medicine. A study by Chinese and British scientists finds that, in areas where commercial harvesting is intense, the flower has evolved to be less conspicuous, changing from a bright green to a brown or grey that blends in with surrounding terrain.

In the New York Times, Jessica Bennett profiles Loretta J. Ross, a radical Black feminist professor who’s fighting “call-out culture.” Her weapon of choice? “Calling in.” Calling in is “a call out done with love”—that is, in private, with compassion and respect. Ross, a visiting professor at Smith College, believes that “we actually sabotage our own happiness with this unrestrained anger. And I have to honestly ask: Why are you making choices to make the world crueler than it needs to be and calling that being ‘woke’?”

Trump deeply disturbed the Blob this week with his plans to cut the number of troops in Afghanistan in half by the end of the year. In Responsible Statecraft, Andrew Bacevich and Adam Weinstein criticize foreign policy elites for freaking out: “Even as the dysfunction that has characterized the war is widely recognized, few in the foreign policy establishment are willing to consider the possibility that its continuation no longer serves the interests of the United States.” Meanwhile, one of several CIA-backed paramilitary groups in Afghanistan has come under fire for allegedly killing over a dozen civilians in a series of raids last month. In Foreign Policy, Emran Feroz reports that “many Afghans want the groups disbanded when the United States withdraws.”

In Aeon, anthropologist James K Rilling reviews research, including his own, into the biological effects of becoming a father—such as a drop in testosterone, a hormone that, in other species, has been shown to be inversely correlated with a male’s parental devotion. “We have known for decades that mothers’ bodies and brains are transformed by the dramatic hormonal changes of pregnancy and childbirth,” writes Rilling. Now we’re learning that men are “biologically transformed by the experience of becoming an involved father.”

Ok that’s it! Thanks for reading. Send lavish praise or bitter denunciation to nonzero.new@gmail.com. And follow us on Twitter—after which you’ll be perfectly positioned to retweet us, which we always appreciate.

Illustrations by Nikita Petrov.

https://www.customerservice-directory.com/blog/why-is-sbcglobal-net-email-not-working/

https://ijcanonnstart.com/ij-start-cannon/