Pete Hegseth’s Islam Problem

Plus: AGI Manhattan Project, Putin’s nuclear warning, AI dominates doctors, Gaza’s gang problem, Trump’s WWE nominee, and more!

Fox News personality Pete Hegseth, Trump’s nominee for secretary of defense, may be regretting his decision to attend a 2017 conference held by the California Federation of Republican Women. His sexual encounter with one of those Republican women (which happened, as the Wall Street Journal notes, while he was “in the midst of getting a divorce from his second wife after fathering a child with a producer at the network”) led to a sexual assault allegation, and a subsequent hush-money payment, that have together complicated his path to the Pentagon.

But maybe Hegseth should consider this scandal a blessing. If it weren’t for the questions being raised about past sexual transgressions, more attention might be paid to questions that bear more directly on his qualifications to head the Defense Department. There’s the lack of managerial experience in a man who aspires to run the world’s largest military. There’s the fact that he has repeatedly spoken up in defense of US servicemen who had committed vicious war crimes. And then there’s the thing that has gotten the least attention of all but may be the most important of all: Hegseth’s warped views about Islam—views that, if he becomes secretary of defense, could exacerbate conflicts and even create new ones.

In his 2020 book American Crusade, Hegseth argues that Islam “has been at war with its enemies—meaning all ‘infidels’—since it was founded, and it will never stop.” In truth, the Islamic empires of the past—from the seventh century through the early twentieth century—typically included large populations of non-Muslims who practiced their religions in peace, in keeping with Islamic doctrine, so long as they paid a special tax called a jizya. This may not sound progressive by modern standards, but if you compare, say, the treatment of Spanish Jews under Islamic rule to their treatment under subsequent Christian rule, you’ll see that things could have been much worse.

And as for Hegseth’s claim that “all modern Muslim countries are either formal or de facto no-go zones for practicing Christians and Jews”—well, somehow NZN managing editor Connor Echols, a practicing Christian, managed to live in Jordan for a year recently without issue. He even attended church there!

Hegseth seems to see much of the world’s turmoil as a single great struggle between Islam and the West—a struggle, indeed, that extends into the West. He laments high birth rates in western Muslim communities and argues that Islamists, who he says dominate Islam, hope to “seed the West with as many Muslims as possible” in order to gradually conquer more territory.

If Hegseth becomes secretary of defense, his day-to-day work will be colored by his ideas about Islam. Roughly 40,000 US soldiers are stationed in the Middle East, and the vast majority of them are in Muslim-majority countries. Hegseth’s job would involve important meetings with foreign military leaders, and many of them would be Muslim. (And NATO member Turkey is led by Islamist Recep Tayyip Erdogan.) If Hegseth’s expressed views about Islam are sincere, he’ll have trouble viewing the people he’s meeting with as rational actors. And even if they’re not sincere, they’ll be known to, and not welcomed by, those people.

There’s a deeper clash between Hegseth’s worldview and his ability to serve American interests. Wisely advising a president on the deployment of force requires a sound understanding of conflict and its causes. If you trace all conflicts involving Muslim nations and non-state groups to some imagined eternal essence of Islam, you’ll miss a lot of important causal factors. Like, for example: grievances over past dispossession and enduring oppression (as with Palestinian Muslims and Christians, whose shared views on Israel, and America’s military support of Israel, must baffle Hegseth); or nationalist reactions against foreign military occupation (as with some attacks on US troops in Iraq); or national security calculations (as with Iran’s support of some attacks on US troops in Iraq).

And as for the home front: Most “Jihadist” terrorism on US soil has been motivated not by the fact that America is a Christian-majority nation but by the perception that the American military has spent much of the past two decades conducting a war on Islam—a perception articulated explicitly and repeatedly by the terrorists themselves in justifying their crimes. It would be bad enough to have a secretary of defense who doesn’t understand this perception. With Hegseth we’d have a secretary of defense whose stated views on Islam feed the perception.

It’s possible that when George W. Bush, in the days after 9/11, called America’s coming war on terrorism a “crusade,” he wasn’t fully aware of the unfortunate historical resonance of that word. But when Hegseth chose to call his book “American Crusade,” he was quite aware of the reference to Medieval wars between Christendom and Islamic empires. He writes, “Our present moment is much like the 11th Century. We don’t want to fight, but, like our fellow Christians one thousand years ago, we must.” He advises readers to “Arm yourself—metaphorically, intellectually, physically… Our fight is not with guns. Yet.”

No, not yet. Then again, Pete Hegseth isn’t secretary of defense. Yet.

Echo chambers are good, actually. So argues James Marriott, a columnist at The Times of London, in a piece that applauds the ongoing exodus of liberals from X (aka Twitter) to rival social media site Bluesky. “Online rage” he writes, “results from people seeing too much of their maddest political opponents.”

On the other hand, there’s value in trying to understand the perspective of your ideological adversaries—and X, for the time being at least, is a place where both liberals and conservatives can do that. As Jemima Kelly of The Financial Times writes, “[W]hile it will always be much messier and more maddening than we might like, I believe such a place is preferable to a series of siloed echo chambers.”

We at NZN, faced with these two views—and the corresponding choice of whether to move from X to Bluesky—chose not to choose. We’re staying at X—where you’ll continue to find the accounts for both the NonZero Newsletter and the NonZero podcast—but we’re also opening a second social media front on Bluesky. There, in a masterstroke of brand unification, we’re consolidating newsletter and podcast into a single NonZero account. We encourage you to follow it if you’re exploring Bluesky.

Also, we had our proprietary large language model scour Bluesky for the personal accounts we think you’d find most interesting, and here they are: Robert Wright and Connor Echols. Our LLM predicted that you would also enjoy the Bluesky accounts of Andrew Day and Clark McGillis should they come into existence. We’ll let you know when they do.

As Trump selects nominees for top government positions, NonZero brings you a few updates, followed by a chance to put your forecasting skills to the test:

—Trump’s choice for energy secretary is Republican donor Chris Wright, a fracking executive who last year said that “there is no climate crisis, and we’re not in the midst of an energy transition.”

—Trump tapped Linda McMahon, a former CEO of World Wrestling Entertainment (who has stepped into the ring herself!), as education secretary. During a 2010 race for the US Senate, McMahon had to retract the claim that she had a bachelor’s degree in education. Her real major was French.

—Trump named Brendan Carr as the next chairman of the Federal Communications Commission. Carr, who has become a staunch ally of Elon Musk, has called for Starlink, a Musk-owned company, to be included in a multi-billion-dollar government program of broadband expansion. He has also said he plans to give close scrutiny to X rival Facebook and other members of what he calls the “censorship cartel.”

—Even after this week’s spate of picks, Trump’s most controversial nominees are still Tulsi Gabbard for director of national intelligence and Pete Hegseth for secretary of defense. (Matt Gaetz—Trump’s nominee for attorney general—withdrew from consideration amid allegations involving illegal drugs and sex with a teenager who was paid for her services.)

NZN readers, we turn to you: What are the chances that the Senate rejects at least one of these cabinet-level nominees? Head over to NonZero’s Metaculus community to submit your forecast.

The US amped up military support for Ukraine in two ways this week, and one of them was deemed escalatory by Russian President Putin, who responded with a kind of counter-escalation.

First, President Biden authorized Ukraine to strike deep into Russian territory with US-supplied long-range missiles—which Ukraine did on Tuesday. Then Putin amended Russia’s nuclear doctrine, lowering the threshold for the use of nukes. Under the new guidelines, nuclear retaliation is possible when any nation supported by a nuclear power attacks Russia with conventional weapons.

Then, as if to drive the point home, Russia, for the first time ever, hit Ukraine with a multiple-warhead ballistic missile—a missile designed to accommodate nuclear warheads. After the strike, Putin raised the prospect of also striking US or British targets. (Britain had followed Biden’s lead by authorizing Ukraine to use its air-launched Storm Shadow missiles against targets in Russia, which Ukraine promptly did.) Russia, Putin said, has the right to strike “military facilities of those countries that allow their weapons to be used against our facilities.” He had previously warned that if Biden crossed the threshold he crossed this week, the West and NATO would be in direct conflict.

The US also announced this week that it will send anti-personnel landmines to Ukraine. The move reverses a policy laid down by Biden in 2022, when he revived an Obama-era ban on using or transferring such mines outside the Korean peninsula. In 2020 Biden had called then-President Trump’s reversal of the Obama ban “reckless,” saying “it will put more civilians at risk of being injured by unexploded mines, and is unnecessary from a military perspective.” More than 160 countries have signed the Ottawa Treaty, which bans anti-personnel mines, but the US and Russia have not.

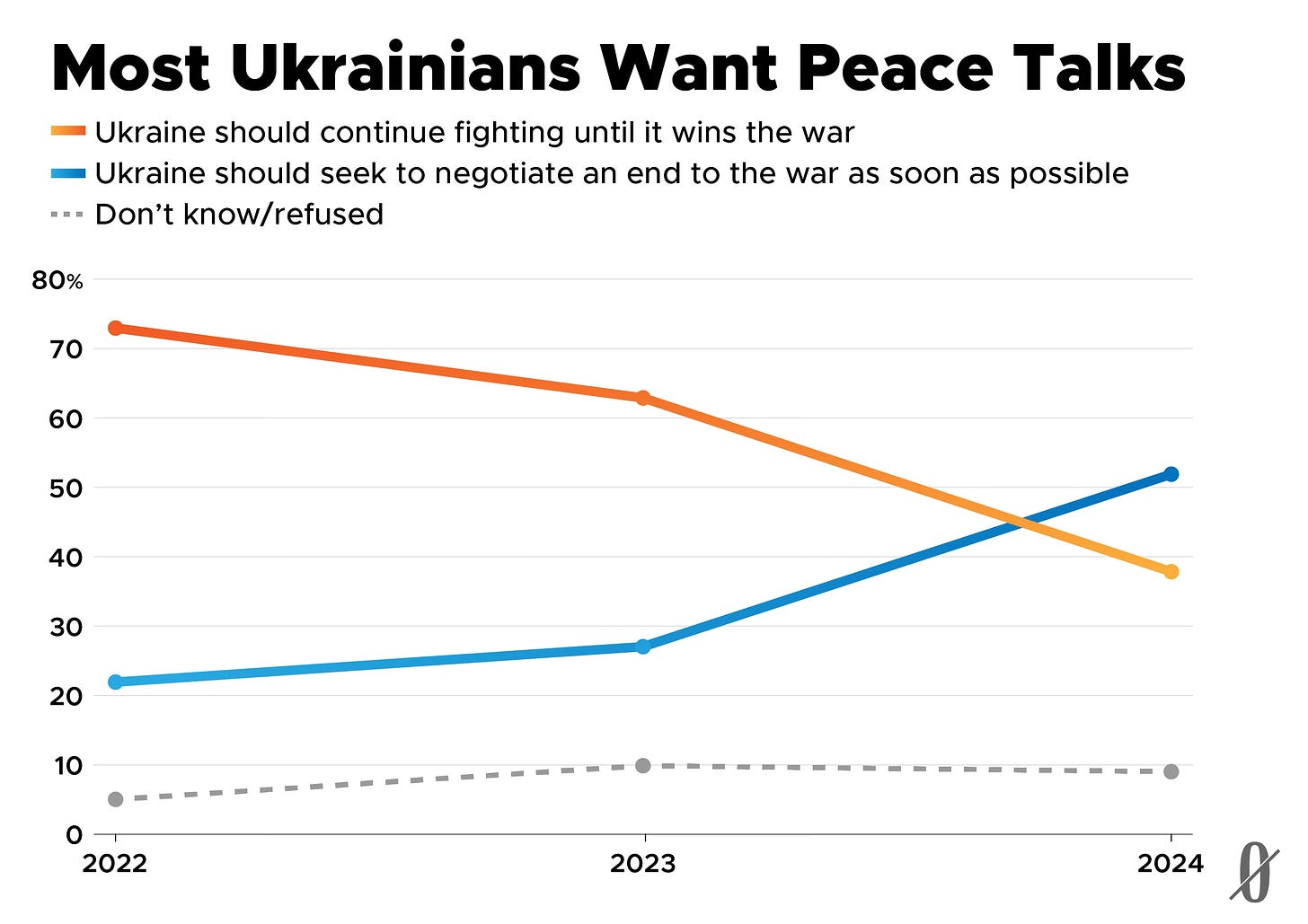

Both US moves came amid growing Russian success on the battlefield, and growing fears that a breakthrough somewhere along Ukraine’s front line could lead to rapid Russian gains. The moves also came amid signs that the Ukrainian people are increasingly supportive of a peace deal even if that leaves Russia in control of some Ukrainian territory. A recent Gallup poll found that, for the first time, more than 50 percent of Ukrainians want their government to “negotiate an ending to the war as soon as possible.”

AI updates—medical edition:

—Should doctors use large language models as diagnostic aids? A study designed to answer that question wound up raising a different question: Should large language models use doctors as diagnostic aids?