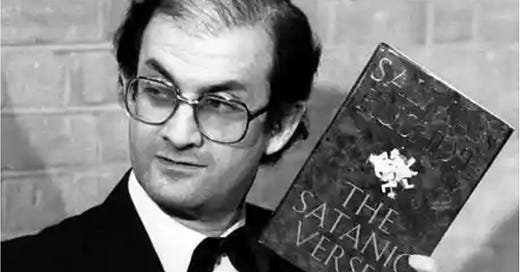

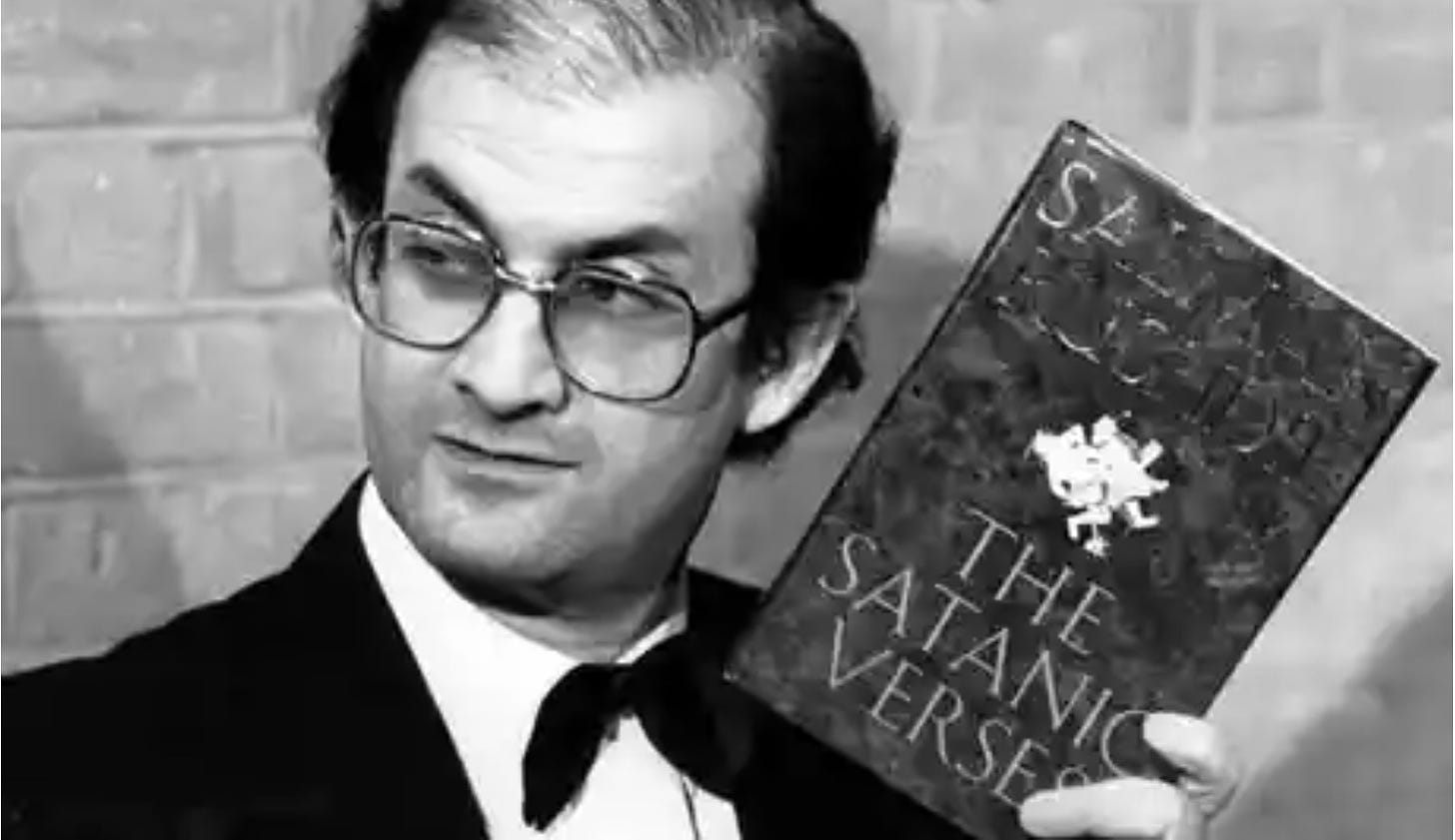

Salman Rushdie and the Clash of Civilizations

The 1989 fatwa against him helped trigger a debate that looks different in the rear view mirror

The mother of Hadi Matar, the man who stabbed Salman Rushdie last week, characterizes her son this way (as paraphrased in the New York Post): “a basement-dwelling loner who barely worked” and “never had a girlfriend.” The basement he dwelt in was his mother’s. She describes her relationship with him this way: “If I approach him sometimes he says hi, sometimes he just ignores me and walks away.”

Back in 1989, when the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini issued a fatwa calling for the death of Rushdie as punishment for blasphemous writings, I didn’t spend a lot of time trying to visualize the kind of person who would respond to Khomeini’s call. But if I had, the result wouldn’t have looked like Hadi Matar. The Rushdie attacker of my imagination would have looked less like a—how can I put this delicately?—less like a loser than Matar does; less like some deranged ne’er-do-well plucked from the headlines of the latest high-profile atrocity.

To put a finer point on it: The Rushdie attacker of my imagination would have looked less like Payton Gendron, the 18-year-old who three months ago shot up a Buffalo supermarket under the inspiration of “replacement theory” and who, until that day, had spent much of his time in the trailer home of his only friend, playing video games. The friend’s girlfriend said this of Gendron: “After 11th grade he was considered weird because he did not talk much.” As a result, nobody—aside from her boyfriend—“wanted to spend time with him.”

The Khomeini fatwa of 1989 helped set off an effort by western intellectuals to reckon with a new threat emerging from the east—radical Islam. In 1990 The Atlantic published its famous cover story “The Roots of Muslim Rage,” by the eminent scholar of Islam Bernard Lewis. Lewis’s diagnosis: “This is no less than a clash of civilizations—the perhaps irrational but surely historic reaction of an ancient rival against our Judeo-Christian heritage, our secular present, and the worldwide expansion of both.”

Not everyone bought Lewis’s inter-civilizational warfare paradigm, but it did capture something that was more commonly believed back then than now, something that probably shaped my assumptions about the kind of person who might eventually attack Rushdie. Namely: that the threat of radical Islam possesses a kind of large-scale coherence and cohesion; that we can think of this enemy much as we’re accustomed to thinking of wartime enemies—as a group of disciplined warriors (if a bit more fanatical than enemy warriors of yore) bound by shared motivation and under firm leadership. In this conception of radical Islam, Khomeini’s foot soldiers should look kind of like foot soldiers, not like guys living in their mother’s basement.

In retrospect, I think Lewis’s framing was pretty fundamentally off the mark. If I’m right, that’s in one sense good news; a threat against the West that emanates coherently from “Islamic civilization” sounds like it would be pretty formidable.

But in a way it’s bad news if I’m right about what Lewis got wrong. One thing I think he failed to see is the sense in which the threat of radical Islam is part of something even bigger than “Islamic civilization,” something that transcends individual civilizations, something that draws energy from tectonic shifts that encompass the whole world and show no signs of abating.

I think that it’s this bigger, more generic threat that Hadi Matar is most consequentially an expression of—and that this is something he has in common with Payton Gendron.

Before explaining what I mean, let me throw in a third case that, I think, is a product of the same generic forces that brought us the Buffalo shooting and the Rushdie stabbing: the Uvalde school shooting.

That was the work of 18-year-old Salvador Ramos. Ramos was a high school dropout who had been fired from two fast-food jobs. He had stayed enrolled in school through the Zoom phase of the Covid pandemic, but as the pandemic waned, and other students returned to school, Ramos—having completed only 9th grade at age 17—didn’t. The Texas Tribune reports, “Instead of trying to fit in, as he had done in the past, he grew more isolated and retreated to the online world.”

So what do these three men have in common? Two things: