This is a free edition of the Nonzero Newsletter. If you like it and you’re not already a subscriber to the paid version of the newsletter (aka The Apocalypse Aversion Project), I hope you’ll consider becoming one.

The 20th anniversary of 9/11 has come and gone, leaving us with, among other things, tons of retrospective assessments of the Global War on Terrorism. It’s time to assess the assessments! What evidence is being brandished by those who deem GWOT a success and by those who deem it a failure? And whose evidence wins?

I figured I’d try to shed some light on this situation by reading the official New York Times GWOT assessment, but I found myself immediately confused. After a headline that was clear and accurate (“20 Years On, the War on Terror Grinds Along, With No End in Sight”) came this subhead: “The failures in Iraq and Afghanistan obscure what experts say is the striking success of a multilateral effort that extends to as many as 85 countries.”

Wait. How much of a “striking success” can the war on terror be if we’re now pursuing it in “as many as 85 countries”? You don’t hear doctors say, “Our treatment of the patient’s cancer has been a striking success, and we’re now targeting more of his organs than ever with chemotherapy.”

In trying to resolve this paradox, I scanned the Times piece for the “experts” who have deemed GWOT a striking success. The only expert quoted to that effect was Daniel Benjamin (who, having been the State Department’s coordinator for counterterrorism in the Obama administration, may not be the most impartial evaluator of America’s counterterrorism effort—but I digress…). Benjamin says, “If you had said on 9/12 that we’d have only 100 people killed by jihadi terrorism and only one foreign terrorist attack in the United States over the next 20 years, you’d have been laughed out of the room.”

That may be true. There was certainly a sense, after 9/11, that we’d be lucky to go a couple of decades without another 9/11. On the other hand, you might have gotten a few laughs if you’d predicted that in two decades we’d be pursuing the war on terror in 85 countries. Especially if you showed people what that would look like on a map (assembled by Brown University’s Costs of War Project, which is where the Times got the 85 countries figure):

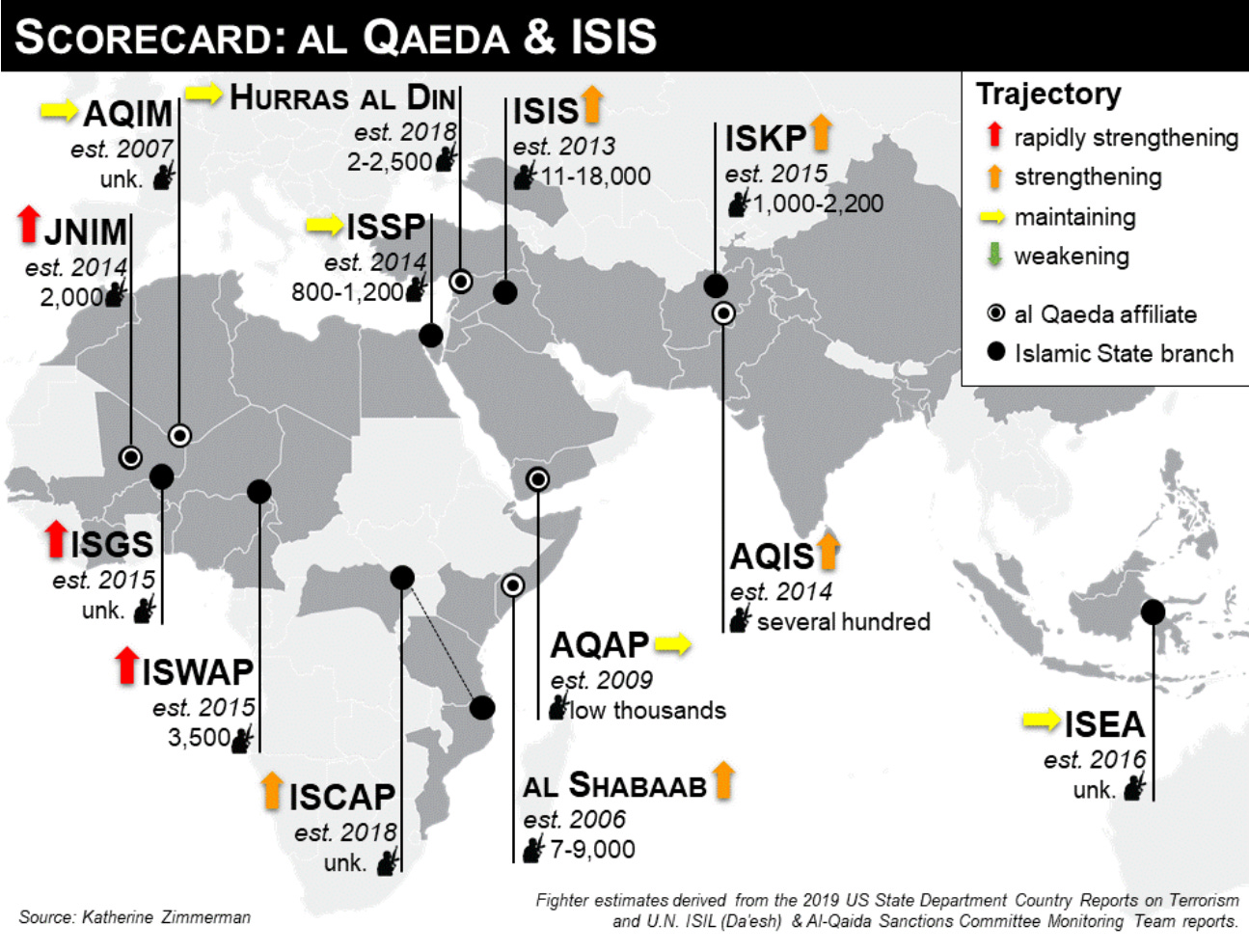

Or suppose that, on 9/12, you’d shown people a 2021 map of al Qaeda affiliates—plus the affiliates of something called “the Islamic State”:

So what’s going on here? Why has the war on terror gone pretty well by one metric—number of people killed in America by terrorists—and pretty badly by another: the proliferation of terrorist groups? And which metric should we use? Should we applaud or indict the various presidents who shaped and pursued the Global War on Terrorism?

I vote for indictment. I think these presidents have something in common that helps explain both metrics—and that in the long run will be seen as strategically misguided and morally problematic. Namely: All of them focused, not surprisingly, on preventing terrorist attacks in the US on their watch—but they pursued that goal in ways that aided the spread of jihadism and that have planted the seeds for more terrorism down the road.

This pattern started almost immediately after 9/11. Yes, Bush’s invasion of Afghanistan incapacitated al Qaeda in the short run—but US troops occupying a majority-Muslim country was in the long run a Godsend for terrorist recruiters, both abroad and at home. (Most of those 100 Americans killed in jihadist terrorist attacks since 9/11 were killed by people who cited as motivation US military activity in majority-Muslim countries.)

Then came the invasion of Iraq—a product of various factors, but among them, I think, Bush’s genuine belief that this war would keep weapons of mass destruction out of terrorist hands and so keep the homeland safe. Once again, US troops occupying a majority-Muslim nation would be grist for the jihadist recruiting mill. And Bush’s contribution to terrorism didn’t end there. It was amid the chaos he created in Iraq that the precursor of the Islamic State took shape—and ISIS now has affiliates in at least half a dozen countries.

President Obama, while refraining from invasions, radically ramped up the use of drone strikes. And he seems to have been guided less by a long-term anti-terrorism master plan than by an acute aversion to a big terrorist attack happening on his watch. He was said to have been shaken by the “underwear bomber”—the hapless terrorist who tried but failed to blow up a US-bound airliner less than a year into Obama’s first term—and determined not to let any such plot succeed.

The drone strike Obama launched in response to the underwear incident illustrates how little thought he gave to long-term consequences.

It targeted Anwar al-Awlaki, a Muslim cleric who had moved from America to Yemen, where he had encouraged and advised the underwear bomber. A bit of calm reflection might have led Obama to wonder whether, given the number of video lectures by Awlaki available online, turning him into a famous martyr might prove ill-advised. And indeed, in 2015 the New York Times reported: “Four years after the United States assassinated the radical cleric in a drone strike, his influence on jihadists is greater than ever… The list of plots and attacks influenced by Awlaki goes on and on. In fact, Awlaki’s pronouncements seem to carry greater authority today than when he was living, because America killed him.”

And by the way, Awlaki’s initial radicalization may have been a product of President Bush’s unsparing use of domestic surveillance to minimize the chances of terrorism on his watch. Awlaki had shown no clear signs of radicalism until after he learned, in 2002, that the FBI was spying on him and had found compromising information about his sex life. For a prominent Muslim cleric, this was catastrophic news. He fled to Yemen and only then started talking about the US as an enemy.

President Trump continued Obama’s policy of liberal drone strikes—and, in a sense, made it more liberal. He gave commanders in the field more latitude in ordering strikes and weakened rules designed to reduce civilian casualties.

Trump did try to do something that might have, in the long run, complicated life for terrorist recruiters: withdraw US troops from various Middle Eastern countries. But he was no match for the foreign policy establishment, and it wasn’t until the Biden administration that one of these efforts led to actual withdrawal.

Biden is being championed by opponents of “forever wars” for that withdrawal—and I join in commending him for getting us out of Afghanistan. However, in reassuring critics of the withdrawal, he says we’ll use “over the horizon” capabilities as needed in Afghanistan and elsewhere. Which is to say, drone strikes or other aerial strikes that, especially when they kill civilians, can create time-release fuel for terrorism. The final drone strike of the Afghanistan war—the one in Kabul two weeks ago that was supposed to kill aspiring suicide bombers but instead killed a worker for an American NGO and several of his children—was not auspicious.

Of course, the other problem with killing innocent civilians—aside from the fact that we’re doing terrorist recruiters a favor—is that we’re killing innocent civilians. If you drop, for just a moment, our natural focus on the number of Americans killed by terrorists, and think about the foreigners killed in the Global War on Terror—including but not confined to the hundreds of thousands of civilians killed in wars or by out-of-theater drone strikes—it becomes hard to understand how the Global War on Terrorism can be judged, in moral terms, anything but a disaster.

I mean, I get that national governments always value the lives of their citizens over foreign lives. But isn’t there some limit on the acceptable rate of conversion?

The good news is that reining in the war on terror—moving that 85 countries figure steadily downward—isn’t as scary as some people think. In many parts of the world where we sense a brewing terrorist threat that we must counteract to keep America safe, there isn’t really a brewing terrorist threat that we must counteract to keep America safe. There is, rather, a local conflict, and there is some government or some faction that is eager to get American military support so it can prevail in that conflict—and is more than happy to assume the anti-terrorism mantle if that will do the trick.

And it often happens that providing that support actually hurts America’s national security; we turn ourselves into the enemy of some group that would otherwise have its eyes trained on a local rival—a rival that, for all we know, isn’t worthy of the support we’re giving it. (Only last Friday, much to America’s embarrassment, some troops that US special forces had trained in Guinea used their newfound prowess to stage a coup that the US then condemned. “American military officials,” reported the Times, “said they had no warning of what their students were planning.” There is some evidence that, to execute the coup, the students “slipped away while their instructors were sleeping.”)

I’m not saying that radically revising our misguided GWOT strategy would bring no risks. Just as expanding the compass of the war on terror sometimes saved lives in the short term at the cost of more lives down the road, shrinking that compass might do the opposite: make us more secure in the long run at the cost of short-term vulnerability. A true steward of the national interest would take that deal.

Spencer Ackerman, author of the new book Reign of Terror: How the 9/11 Era Destabilized America and Produced Trump, recently recounted an exchange he had with Ben Rhodes, one of Obama’s foreign policy aides. He asked Rhodes “why they didn’t dismantle the war on terror, particularly after they had the opportunity once they killed Bin Laden. And his answer was, ‘Imagine if he does what you wanted him to do and there’s another terrorist attack and the world ends.’ And what he really means is not the world ending, but that’s the end of Obama’s presidency.”

What America needs is a president who doesn’t equate big political setbacks—even potentially career-ending setbacks—with the end of the world. The world needs that too.

What are the domestic political incentives to continue the GWOT? That Rhodes story illustrates what they *think* the incentives are but what if they’re wrong? It could very well be that the majority of the electorate doesn’t support endless occupation and liberal drone strikes, but it’s an issue that’s not as high on the radar as the economy, healthcare, etc. Meanwhile the supporters of the endless wars and engagements are simply the loudest voices in the room, and don’t actually represent a broad consensus.

Hi Bob, This comment pertains to all posts about TGWT. I'm reading (I'm disappointed to learn you no longer read books.) George Bernard Shaw, PYGMALION and THREE OTHER PLAYS (2004, 667 pages) and he has a lot to say about our current affairs. He wrote these words over 100 years ago. Which brings me to my point. I read your words of 20 years ago. I'm surprised that given your knowledge of Evo Psych that you still believe that mankind can change is behavior toward world governance. Your position hasn't changed. Mine has - to a strict realist one.

Your post prompted me to go back and look at what I wrote a the beginning of the TGWT. You can read that post here (in which you and NZN are referenced. https://markedwardjabbour.com/2021/09/12/screwed-without-a-kiss/

Back to Shaw. He wrote at the end of WW1, "Hegel was right ... we learn from history that men never learn anything from history." (516) [and] "Truth telling is not compatible with the defense of the realm." (518) [and this gem] "no less than twenty-three wars are at present being waged to confirm the peace ..." (514) [and this] "men who had become rich by placing their personal interests before those of the country, and measuring the success of every activity by the pecuniary profit ..." (500)

The whole of his work is brilliant.

The Pygmalion Effect (social psych) has it's limits. Ozzie Smith cannot become Babe Ruth and vice versa. No matter how much you want it so.

Anyway, I enjoy your posts and discussions. cheers