Hi! Below The Week in Blob—our weekly summary of foreign policy news and the nefarious doings of America’s foreign policy establishment—you’ll find our Progressive Realist report card for National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan.

Withdrawing from Afghanistan by May 1—the deadline agreed with the Taliban last year—is off the table, according to a person “familiar with” Biden administration deliberations who was quoted in Vox. This news is not too surprising, given the way the Blob has recently been deploying its awesome powers. As Daniel Larison of The American Conservative wrote in Responsible Statecraft this week, an ideologically diverse array of influential Blobsters have been proselytizing on behalf of prolonging America’s longest war. These Washington luminaries—including Max Boot, David Ignatius, Madeleine Albright, and Lindsey Graham—“may all be coming from different plot points on the Washington political grid,” writes Larison, “but keeping the United States committed to a desultory, unwinnable conflict unites them.” In other news, talks between the Taliban and the Afghan government have restarted. These negotiations are premised partly on the expectation that the US and its allies will leave the country soon, so they may lose momentum as it becomes clear that this isn’t happening.

Prospects for restoring the Iran nuclear deal—supposedly one of President Biden’s foreign policy priorities—again failed to brighten this week. The Biden administration is reportedly trying to organize a censure of Iran by the International Atomic Energy Agency—even though the US, not Iran, abandoned the deal, and Iran says it will return to compliance if the US makes the first move. The idea seems to be that putting more pressure on Iran will convince it to be the nation that returns to compliance first (a reversal of the natural order of things that, for unclear reasons, matters immensely to the Biden administration). But meanwhile, in Iran, there was a reminder that domestic politics may limit the government’s ability to submit to American pressure. The parliament rebuked President Rouhani’s government for what it considered just such a submission: The government had postponed by three months a planned restriction of UN inspectors’ access to its facilities, a restriction mandated by parliament to pressure the US into lifting sanctions imposed by President Trump after he abandoned the deal. The end of the week brought additional tension between the two countries, as the US staged a military strike against Iran-linked militias in Syria.

A confidential United Nations report found that former Blackwater head Erik Prince violated a UN arms embargo on Libya, according to the New York Times. The document reportedly shows that Prince sent a mercenary force—complete with “attack aircraft” and gunboats—to Khalifa Haftar, a rogue Libyan general whose forces currently dominate the eastern part of the country. The whole operation apparently cost $80 million, though it’s not clear who provided the funding or how much money Prince received. Also unclear is whether Prince will be held accountable for his alleged wrongdoing.

The number of people facing hunger in four Central American countries—El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua—has increased by 400% since 2018, according to a UN report. The report links this rapid rise in food insecurity to a series of major hurricanes, the covid pandemic, and a climate change-related drought.

COVAX—an international project aimed at fighting vaccine inequality—has finally begun to deliver doses to poorer countries. The first batch landed in Ghana on Wednesday, marking a major milestone in the international fight against vaccine nationalism.

Indonesia is sponsoring talks between Myanmar’s military and representatives of the country’s ousted government, according to Reuters. Indonesia is also pushing to coordinate a regional response to the coup through the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), a body that has historically avoided getting involved in the internal disputes of member countries.

During incoming CIA Director William Burns’s confirmation hearing this week, Senator Marco Rubio said that China poses “the most existential” threat to the United States in the world today. Elaborating, Rubio explained that “their goal is to replace the US as the world’s most powerful and influential nation.” In other words, Rubio is arguing that another state challenging American hegemony threatens America’s very existence as a country. Readers opposed to a new cold war will be happy to learn that Burns responded by drawing a clear distinction between the threat once posed by the USSR and the one currently posed by China, arguing that the latter is more about economics and technology than ideology and security.

Readings

In Foreign Policy, activist and lawyer Fatima Hassan argues that the World Trade Organization must temporarily waive intellectual property rights on vaccines in order to avoid repeating the mistakes of the HIV/AIDS crisis.

In Responsible Statecraft, researcher Brett Heinz examines how defense industry and foreign government funding affects the work of the Center for a New American Security, a prominent center-left think tank from which Biden has pulled several national security appointees. “CNAS advances the interests of donors in the name of promoting U.S. national security interests,” Heinz writes.

Also in Responsible Statecraft, Annelle Sheline argues that, though the Biden administration has complained about human rights violations in Saudi Arabia and claims to be ending support for the Saudi military intervention in Yemen, little has changed in terms of concrete policy.

In Foreign Exchanges, Derek Davison goes after American media outlets for their coverage of the diplomatic stalemate with Iran. His polemic is worth quoting at length:

“The Biden administration would like you to know that it’s trying to revive the JCPOA but its good faith efforts are being rebuffed by the Iranians. It seems clear that somebody has turned on the Bat-Signal as far as US media outlets are concerned, because several of them have churned out versions of this narrative over the past couple of days. The AP’s version is indicative. This is propaganda. Although Joe Biden and his foreign policy team have talked a lot about diplomacy with Iran, it was only a few days ago that they actually took some tangible steps in that direction and those were mostly cosmetic. Despite frequently criticizing the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” approach toward Iran, Biden has left the entire Trump sanctions apparatus in place. Yes he’s only been in office a bit over a month, but the steps he’s taken thus far could have been taken on day one and might actually have gotten a positive reception from Tehran. But now, after a month of delays and demands that Iran take the first steps to fix an agreement that the US broke, they’re too little and maybe too late.”

—Robert Wright and Connor Echols

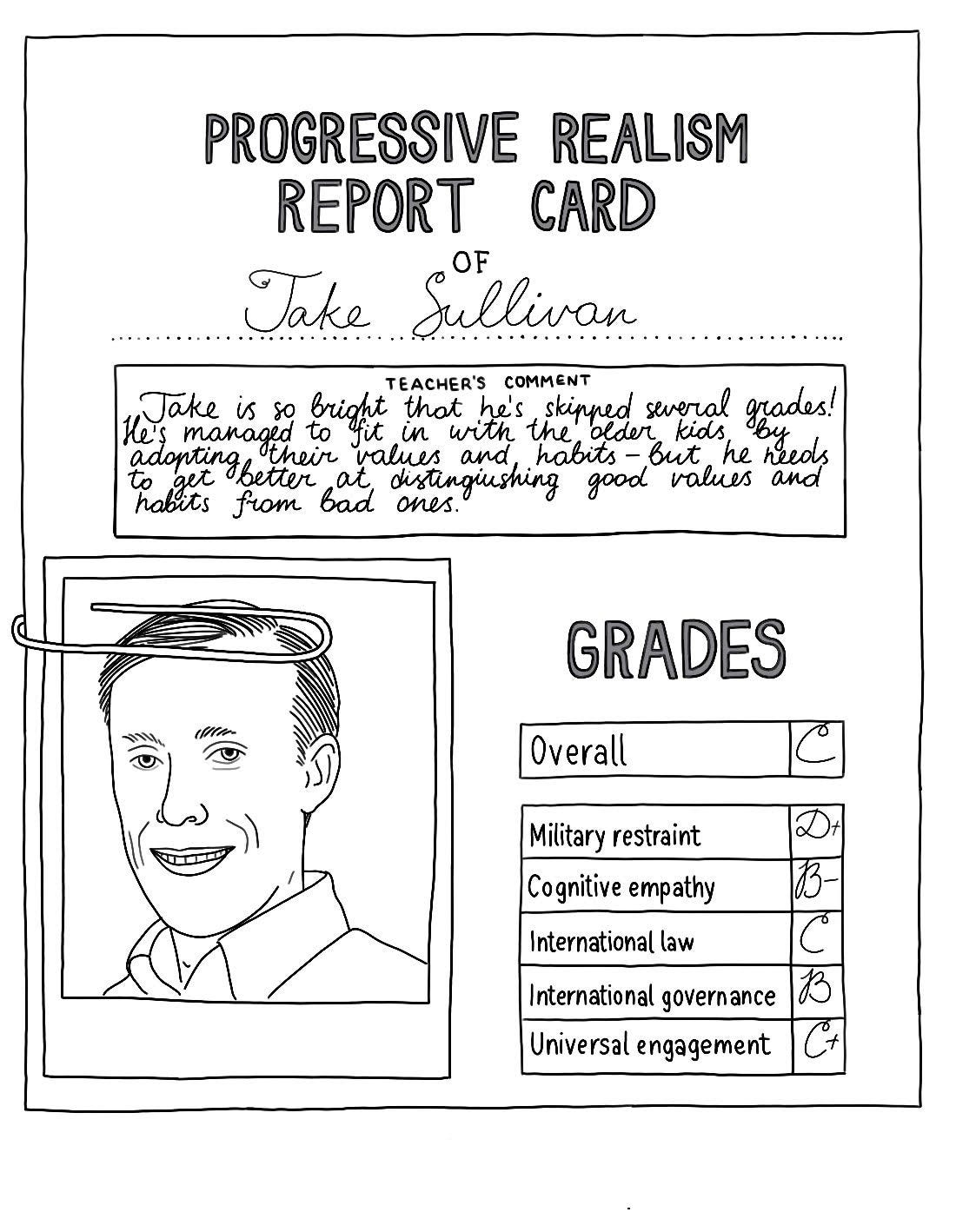

Grading Jake Sullivan

Background:

Sullivan, 44, is the youngest person to serve as the president’s national security adviser since McGeorge Bundy served in the Kennedy administration. He is more hawkish than Biden, but he brings, from his Obama administration days, experience that could prove valuable, especially as the Biden team tries to revive the Iran nuclear deal that Trump abandoned.

For our grading criteria, click here.

Military restraint (D+)

While serving in Hillary Clinton’s State Department, Sullivan pushed for proxy intervention in Syria and direct intervention in Libya, both of which fueled humanitarian crises and were regionally destabilizing. Subsequently, while serving as national security adviser to then-Vice President Biden, he recommended sending weapons to Ukraine in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its support for rebels in eastern Ukraine. Obama aide Ben Rhodes has said of Sullivan: "On the spectrum of people in our administration, he tended to favor more assertive US engagement on issues" and "responses that would incorporate some military element."

Of particular relevance to the Biden era of US foreign policy, Sullivan favors an assertive approach to China. He has advocated increasing naval operations in the South China Sea as a way of “demonstrating that the world rejects China’s claims to these waters and forcing Beijing to decide whether to stop us.”

On the plus side, Sullivan had opposed America’s role in the war in Yemen even before the announcement that Biden would end support for Saudi offensive actions there. And he has expressed a desire to bring the war in Afghanistan “to a responsible close.” But the word “responsible” provides a lot of wiggle room. And Sullivan has said that ending “forever wars” like the one in Afghanistan “doesn’t mean abandoning the region or shutting down the counterterrorism mission.” That leaves the door open for ongoing involvement in a lower-profile war on terror that could leave American soldiers (not to mention the citizens of Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Afghanistan, Somalia, Pakistan, and various other countries) in harm’s way.

Cognitive Empathy (B-)

Sullivan sometimes attributes to other nations more threatening aspirations than can confidently be inferred from their policies. In an essay in the Atlantic, he warned of “China’s long-term strategy to dominate the fastest-growing part of the world, to make the global economy adjust to its brand of authoritarian capitalism, and above all to put pressure on free and open economic and political models.” In truth, it’s not clear that China objects to free market economies or liberal democracies so long as it can structure relations with them in ways it finds commercially and strategically profitable. (Also unclear is how its aim to “dominate” its neighborhood differs from America’s longstanding insistence on dominating its own neighborhood.) Similarly, Sullivan’s assertion that Russia is pursuing a “strategy to spread neofascist ideology” overstates Vladimir Putin’s discernible goals.

Sullivan’s assessment of the perspectives and aims of leaders in other countries—most notably Iran—seems more acute. He helped negotiate the Iran deal and later dismissed Mike Pompeo’s demands of Iran’s leaders—which included ending support for proxies in Lebanon and Syria and getting rid of their ballistic missile program—as “simply unrealistic and unreasonable.” And Sullivan is more willing than some in the foreign policy establishment to acknowledge Iran’s natural role as a significant regional player. “Ultimately, a solution to the Middle East is going to have to involve some grappling with the existence of Iranian power and influence in some parts of the region,” he said last year.

Respect for international law (C)

Sullivan is a proponent of multilateralism and had harsh words for Trump’s withdrawals from treaties and other agreements. But he tends, like many in the foreign policy establishment, to be more sensitive to foreign violations of international law than to American violations.

On the one hand, he emphasizes the importance of getting China to comply with international law, especially on issues related to trade and human rights—a laudable goal. But he has supported interventions that violate the sovereignty of nations, such as the provision of weapons to Syrian rebels and the stationing of US forces in Syria—both highly dubious under international law.

Sullivan’s interventionist inclination may grow out of his unabashed American exceptionalism—and, like other exceptionalists, he may not realize how often the zealous promotion of American values leads to their violation. He was involved, for example, in the Obama administration’s attempt to orchestrate a transition of power in Ukraine that culminated in the coerced ouster of its democratically elected president.

Support for international governance (B)

Sullivan has a strong record of pursuing multilateral efforts to address non-zero-sum challenges. He was an architect of the Iran nuclear deal and loudly called for the Trump administration to return to that framework. He also argues for prioritizing climate change and using trade deals to target tax havens.

And Sullivan gets credit for recognizing the need to establish international norms to govern the use of nascent technologies that could prove problematic if allowed to evolve in a context of unrestrained international competition. “From artificial intelligence to biotechnology, autonomous weapons to gene-edited humans, there will be a crucial struggle in the years ahead to define appropriate conduct and then pressure laggards to get in line,” he wrote in 2019. “Washington should start shaping the parameters of these debates without further delay.” It would be nice to hear him add that in some cases norms won’t be enough, and binding treaties will be in order.

Sullivan recently proposed an interesting (if nebulous) strategy for addressing some problems facing the Middle East. In Foreign Affairs, he and Middle East specialist Daniel Benaim made the case for a “structured regional dialogue” aimed at getting Saudi Arabia and Iran to the negotiating table with a very limited American role in the ensuing talks. The hope is that this would allow for an informal version of regional diplomatic forums like the Organization of American States or the African Union. (A formal version would bring up the dicey question of whether to include Israel.)

But one major issue prevents Sullivan from getting an A in this category: his hawkish stance toward China and Russia. This could complicate the task of enlisting their cooperation in dealing with various international problems that affect America’s national security—many of which, such as climate change, Sullivan recognizes as important.

Universal engagement (C+)

Let’s start with the positive: Sullivan has consistently pushed for diplomatic ties with some traditional adversaries like Iran and Cuba. As Biden’s national security adviser, he may well pursue policies that ease sanctions on these countries and ease tensions with them.

But he falls short in other areas.

He has endorsed “doubling down on sanctions” against Venezuela with a “focus on breaking off China, Cuba and Russia from Venezuela through whatever means we have available to us because those, effectively, are the lifelines.” The brutality of the US sanctions regime against Venezuela, coupled with the country’s weak governance, has already helped create one of the worst refugee crises that Latin America has ever seen. Sullivan seems to favor regime change, and this approach could well turn Venezuela into a full-fledged failed state, whether or not President Nicolas Maduro is still around to stand atop the ruins.

Also concerning is Sullivan’s tendency to favor like-minded countries when orchestrating international cooperation, an approach that can not only exclude countries whose cooperation is needed but create tensions with them. Like others in the Biden administration, he favors a “global summit of democracies.” And he wants to join with like-minded countries—some of which felt spurned by Trump—to counter Chinese influence and address international problems (though he does acknowledge that we need to be able to work with China on climate change and nuclear weapons). Multilateral efforts aimed at preventing China from, for example, pressuring international institutions into pushing undemocratic norms are, of course, laudable. At the same time, focusing unduly on strengthening relations with nations we have natural affinities with could lead to an ideologically fragmented world, complicating the challenge of addressing climate change and other international problems.

To be clear, Sullivan has explicitly said that he does not want a new cold war. But some of his policy preferences could lead in that direction. He has called for a limited decoupling of the American and Chinese economies through “enhanced restrictions on the flow of technology investment and trade in both directions” when such restrictions serve national security or human rights.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with this kind of thinking. But:

Many analysts argue that the interconnectedness of the US and China make a new cold war unlikely; the post-World War II Soviet Union had few economic links to America, which made it easy for tensions between the two powers to grow. Though there’s logic behind, for example, a long-term plan to reduce reliance on China for certain vital inputs (rare earth minerals, say, or some pharmaceuticals), the pacifying power of economic interdependence should always be kept in mind.

Miscellaneous:

In his time out of government, Sullivan worked for a strategic consultancy firm called Macro Advisory Partners, whose clients “include mining companies in developing countries, sovereign wealth funds, and the rideshare company Uber,” according to the American Prospect. This isn’t the worst variety of revolving-door behavior—Sullivan didn’t consult for Raytheon or other arms makers—but it does raise ethical questions. Before he severed ties with the firm upon joining the Biden campaign, his biography on the company’s website touted his “unparalleled insights on tech policy, US domestic and national security policy and on new economy issues” before listing his various high-level government roles. A prospective client could have been excused for hoping that Sullivan might use the connections and insider knowledge gained during his government service to help their bottom line.

Overall grade: C

—Robert Wright and Connor Echols

To share the above piece, click here.

My weekly conversation with famous frenemy Mickey Kaus can be found after 9:30 p.m. ET (give or take an hour) this evening on The Wright Show podcast feed or at bloggingheads.tv or the bloggingheads YouTube channel. And our after-podcast podcast—the Parrot Room conversation, which is available to paid subscribers and Patreon supporters—can be found around the same time by going to the NZN Substack home page—right here—and clicking on this week’s Parrot Room episode.

Illustration by Nikita Petrov.

My representative Elissa Slotkin (formerly CIA) posted this regarding Iran nuclear deal: https://twitter.com/RepSlotkin/status/1365778507507376128?s=20. Is this more of blob's hand waving?