Wanted: More Lab-leak Liberals

Plus: Will Bibi wag the dog? Ukraine’s info shortage. Why Cold War II will be worse than Cold War I. And more!

The “lab-leak hypothesis” took a step toward mainstream respectability this week after the Wall Street journal reported that the Energy Department now deems it the most likely explanation of how the Covid pandemic started.

Not a huge step, maybe. Of the six US agencies that have rendered a judgment, four have gone with a “zoonotic” origin, and only two—the FBI and now the Energy Department—consider a security lapse at the Wuhan Institute of Virology more likely. Two others, including the CIA, are agnostic. Still, what was once dismissed as a right-wing conspiracy theory can, increasingly, be openly discussed by non-kooks.

However, as it happens, some of the people who most prominently discussed this week’s news of the Energy Department’s assessment are… not necessarily non-kooks.

Tucker Carlson of Fox News seems to suspect that the pandemic arose from something more sinister than a laboratory mishap—and he found a guest for his TV show who is good at fueling such suspicions. This was the top headline at FoxNews.com following the show’s airing:

Sen. Tom Cotton, meanwhile, tweeted that “being proven right doesn’t matter. What matters is holding the Chinese Communist Party accountable so this doesn’t happen again.”

Making sure that a massively lethal lab leak doesn’t happen in the future does indeed matter. That’s why it would be good if more left-of-center people took seriously the possibility that this pandemic started with a lab leak—because, whether or not it did, it well could have, and it would be nice to make such things (and even worse such things) less likely in the future.

Next week an issue of NZN will elaborate on this theme, and spell out some policy implications of the lab leak scenario. Meanwhile, this plot spoiler: “Holding the Chinese Communist Party accountable” for something we don’t know it did is not at the top of the list.

According to President Biden, there is a global conflict between democracies and autocracies, and the US must play a lead role in this Manichaean struggle by defending democratic values around the globe. Leaving aside whether this is a constructive framing of America’s role in the world (this NZN piece from last year argues in the negative), is it a framing the American public is embracing?

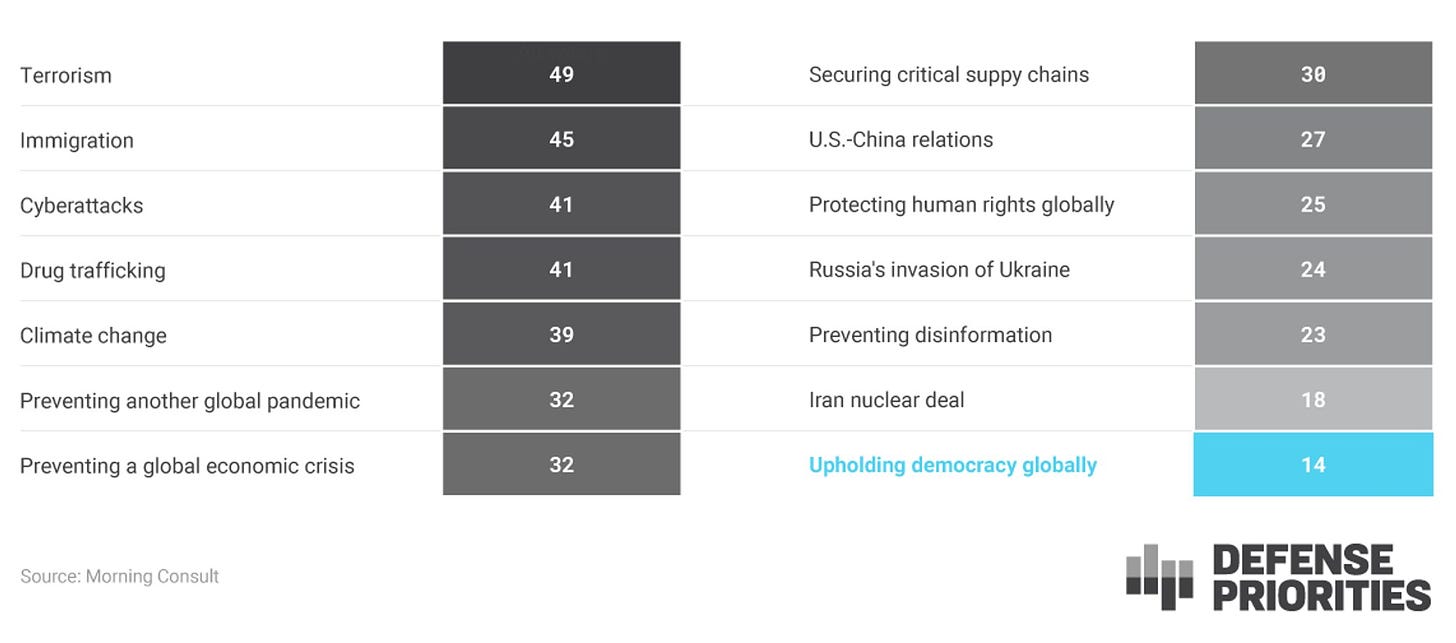

This week, Defense Priorities, a think tank that promotes restraint in US foreign policy, tweeted a graphic that suggests an answer: not so much. The graphic, based on a poll by Morning Consult, ranks 14 issues according to the percentage of Americans who consider them to be among the five most important foreign policy challenges:

Could Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu launch a war against Iran to escape political troubles at home? Yes, according to David Sanger of the New York Times. Speaking on a podcast, Sanger said he thinks there is a “high risk” that “Netanyahu may go off and act against Iran unilaterally as part of a diversion from his own disputes here at home.”

Consider the domestic mess Netanyahu is in:

1. His coalition government faces massive and persistent street protests—a reaction against his plan to legislatively curtail the powers of Israel’s judiciary.

2. He’s on trial for corruption. Indeed, many of those protesters think a primary purpose of increasing his control over the judiciary is to reduce his chances of going to prison. Reining in the judiciary would also give his government a freer hand in cracking down on Palestinians in the West Bank. Which leads to:

3. A cycle of violence in the West Bank is escalating, as lethal government raids on Palestinian militants bring more militant action, and settlers, in response to lethal militant action, start to engage in what look increasingly like pogroms. (Netanyahu’s finance minister embraced the goal of settlers who perpetrated the most recent episode of mass violence, saying the Palestinian town of Huwara should be “wiped out”—but added that the government, not the settlers, should do the honors.)

Meanwhile, Iran is enriching uranium to higher (though not yet weapons grade) levels, and the Biden administration recently said it will stand by Israel if Israel chooses to start a war with Iran—something no previous US administration has said.

What could go wrong?

People who advocate negotiations to end the Ukraine war are sometimes told to be quiet and respect the will of the Ukrainian people. The Ukrainians, it is said, don’t want to talk peace; they want victory—the expulsion of Russian troops not only from all Ukrainian land taken over the past year, but from Crimea and the parts of the Donbass taken by Russian-backed separatists years ago.

There are indeed polls that seem to back up this depiction of popular Ukrainian sentiment. But a piece published in Jacobin raises questions about how well grounded that sentiment is—about whether Ukrainians have access to the information needed to form solid judgments about the costs of continued war and the chances of success.

The main point of the piece, written by staff writer Branko Marcetic, is that authoritarianism has been on the rise in Ukraine; since Putin’s invasion, President Zelensky has centralized power, cracked down on dissent, and put restrictions on media.

Such illiberalizing tendencies are common in countries amid war. But Ukraine wasn’t a paragon of liberal democracy to begin with, and, according to Marcetic, some of its wartime restrictions have been extreme: