Poor Eric Adams. First he becomes mayor of New York at a time when American cities are beset by crime and chaos, and, more generally, the world is spiraling toward apocalypse. Then his administration tries to do something about the apocalypse part and everybody laughs at him!

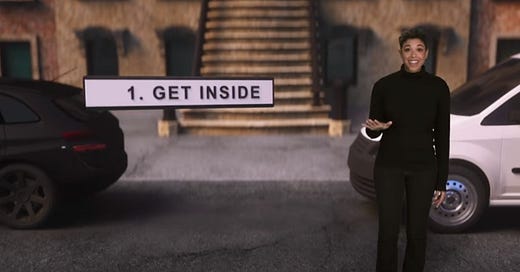

Last week New York City’s emergency management department posted a short video about what to do in case of nuclear attack. (See screenshot above.) The video inspired confusion, dismay, and, as time wore on, ridicule.

Now, granted, it can be jarring to get a video message from your municipal government that begins with a woman declaring, “So there’s been a nuclear attack.”

And, granted, this video does include a few things you could make fun of if you’re the kind of person who can find amusement in videos about nuclear attacks. Since I am that kind of person, I’ll now share my personal favorite:

At the end of the video, having offered a few tips on surviving a nuclear attack, the woman (who, not reassuringly, is dressed like Elizabeth Holmes) says with enthusiastic reassurance, “You’ve got this!”—which just seems kind of funny since (1) among the leading candidates for “least appropriate reaction to a nuclear attack” is “confidence that everything will be fine,” and (2) that confidence would seem especially unwarranted if a video you’d hoped would give you the keys to surviving a nuclear attack wound up just telling you to go indoors, maybe take a shower, and then tune in to a good local news source.

But, all that said, I would like to now speak in defense of this video. Or at least in defense of the idea behind the video—the idea of taking seriously the possibility of a nuclear attack actually happening. After the Cold War ended, this threat pretty much vanished from public consciousness, and it has made only fleeting reappearances since then. I think it deserves a more prominent and enduring place on our radar screen.

And it’s not alone. I think we’re mismanaging our portfolio of existential threats broadly. The amount of attention we pay to the planet’s main catastrophic risks, and the amount of political energy we devote to addressing them, seem not proportional to their actual significance.

If you ask the average liberal what the great existential threat facing the planet is, they’ll say “climate change.” (I don’t know what the average conservative would say. “Liberals”?)

And climate change is a big threat. But there are other ways massive death and suffering could be visited on our species. Nuclear weapons are one. Another is a bioweapon—some lethal virus or bacterium specially engineered to spread like wildfire. And, as hardly anybody needs to be reminded these days, there are nature’s bioweapons: naturally occurring pandemics, including ones much worse than Covid.

And what about cyberweapons? They don’t pack as much punch as nuclear weapons, but if you used them to, say, cripple a nation’s power grid, they could generate enough panic, fear, and uncertainty to put the world on a slippery slope toward a nuclear exchange.

I could go on—I’m good at doomsday scenarios! (Do not get me talking about anti-satellite weapons.) But today I’ll focus mainly on nuclear weapons, while using them to make a larger point: rationalizing our existential threat portfolio could pay big dividends not just for the obvious reason (that we should apportion our attention and energy to threats in accordance with their magnitude) but for a less obvious reason: There’s a kind of political synergy to be harnessed through this rationalization; expanding the list of threats we pay attention to could increase our chances of success in addressing the ones we’re already paying attention to.