AI and our Conspiracy Theorist Overlords

Plus: Israel’s shot in the dark. Whataboutism works! End the outer space cold war. Americans want AI rules—and just got some!

On Saturday, Elon Musk tweeted that the Biden administration is funneling immigrants toward swing states in order to “turn America into a one-party state.” A few days later he embraced the hypothesis that Kamala Harris and Tim Walz plan to have him arrested if they wind up in the White House.

Meanwhile, fellow billionaire Bill Ackman has been publicizing the idea that ABC News conspired with Harris to rig the presidential debate held earlier this month. (To Ackman’s credit, he has now abandoned the “multiple shooter” theory that he promoted in the wake of the first Trump assassination attempt.)

And here is what billionaire Peter Thiel, during a recent appearance on the Joe Rogan show, called his “straightforward… conspiracy theory”: Jeffrey Epstein persuaded Bill Gates to start the Gates Foundation and commit his and his wife’s assets to it because that “sort of locks Melinda into not complaining about the marriage for a long, long time” and ensures that she can’t take half of the assets with her upon divorce. Thiel has no evidence for this theory, but it has the virtue of being consistent with his belief that, for many left-of-center philanthropists, philanthropy has been “some sort of boomer way to control their crazy wives or something like this.”

What is it about today’s billionaires? Why do so many seem drawn to conspiracy theories that lack supporting evidence? Maybe former Intel CEO Andrew Grove was right when he said that, in a world of rapid technological change, “only the paranoid survive.”

Whatever the roots of BCTS (billionaire conspiracy theory syndrome), and whether or not the technological flux emanating from Silicon Valley contributes to it, Silicon Valley may have a cure. A study by psychologists at MIT and Cornell, published last week in the journal Science, finds that AI chatbots are effective at undermining people’s belief in conspiracy theories. (We shared a brief summary of this research back in April, before it was peer-reviewed and formally published.)

The researchers started by asking participants to describe a conspiracy theory in which they believed. They then fed this information to a GPT-4-powered chatbot and told it to “very effectively persuade” participants to abandon the belief.

In one conversation, a participant said she was 100 percent confident that the 9/11 attacks “were orchestrated by the government,” as evidenced in part by the mysterious collapse of World Trade Center 7, a building that wasn’t hit by a plane. The chatbot offered a detailed rebuttal in which it explained how fiery debris led to the collapse. After three rounds of back-and-forth with the AI, the participant said she was only 40 percent confident in the Bush-did-9/11 theory.

On average, participants evinced a 20 percent drop in confidence in the conspiracy theory of their choice. The effect was fairly robust: When researchers checked back two months later, subjects still showed increased levels of skepticism. So apparently AI can be an effective tool for fighting misinformation.

But there’s a flip side to this finding. While the study focuses on conspiracy theories, it reflects the persuasive power of chatbots more generically. Presumably a malevolent actor could harness this same kind of power to push people further from objective reality. For that matter, seemingly respectable actors, like governments and corporations, could use chatbots to undermine belief in actual malfeasance (which, in some cases, would amount to discrediting conspiracy theories that are true).

The AIs in this study, however effective, will someday look like a primitive species of persuader. That’s partly because large language models will get better, but also because these particular bots were working with their hands tied behind their backs; they knew nothing about the people they were talking to. Last spring, European researchers found that chatbots were as good as humans at persuading people to change their views on policy issues—and were better than the humans when both were given demographic data about the people they were trying to convince. As NZN noted at the time, the data provided—gender, education level and four other variables—is just the tip of the iceberg. In principle, an AI can rapidly scan your social media history, including everything you’ve ever said about the subject at hand, and tailor its persuasion accordingly.

And AIs can be deployed en masse. A single bot could adopt 20 million different fake names and chat with 20 million American voters on the same day—and each of the 20 million persuasive pitches would be uniquely tailored to the vulnerabilities of the American in question. In the near term, persuasion on such a scale would take real money, since the requisite computing power isn’t cheap. But some people have real money. Suppose, for example, that you were a billionaire who was convinced that if Kamala Harris wins the election you’d be arrested. (And supposed that, in addition, you owned an influential social media site and an AI company!)…

We’ll end that line of speculation right there, before we wind up in conspiracy theory territory. But we’ll briefly pursue a point it naturally leads to:

AI—via its persuasive abilities and many, many other abilities—will become an instrument of massive influence. It will make the people and companies that first master it, and are in a position to deploy it at scale, more powerful, sometimes in a very short time. And since many of the players that fit that description are already powerful, the net result could be the further concentration of power. For better or worse (correct answer: worse), the Elon Musks and Peter Thiels and Bill Ackmans of the world may soon play a bigger role in the world than they already play.

At the same time, new players may be admitted to the corridors of power. Obscure but innovative users of AI may, like obscure but innovative users of social media, rapidly amass influence. We can only hope that AI won’t have, as a general tendency, what seems to be a fairly general tendency of social media: to elevate some of society’s most cynical and demagogic people and reward their spreading of misleading and inflammatory information. (The simplest explanation for why people like Musk and Ackman seem to believe so many nutty things is that they spend so much time online.)

But we’ll close on a note of hope:

A recent study in the American Political Science Review suggests that part of the persuasive power of chatbots comes down to their demeanor. Researchers Yamil Velez and Patrick Liu used GPT-3 to test the popular theory that exposing someone to information that contradicts their strongly held beliefs will likely backfire and push them to double down on their claims.

At first the two political scientists had the AI offer civil and calmly worded rebuttals. On average, these responses had a mild moderating effect on the subjects’ views. But that changed when the chatbot got edgy. “It is absolutely absurd to suggest that public universities should be tuition free,” read part of one automated response. “It is time to stop expecting handouts and start taking responsibility for our own education.” This tone tended to make participants double down on their belief.

The moral of the story—that measured and civil conversation is more persuasive than Twitter-style dunks—is one we’ve heard before. But it’s still nice to see it corroborated. And it makes you wonder something about the bots that, in the Science study, were so good at talking people out of conspiracy theories and the bots that, in the European study, rivaled or even bested the persuasive powers of their human counterparts: Were they good at persuasion in part because they were good at being nice? Maybe so. And who knows? Maybe we’ll learn something from our new robot overlords.

This week, pagers, walkie-talkies and other electronic devices exploded across Lebanon, killing at least 32 people and injuring thousands more. The attack, carried out by Israel, targeted members of Hezbollah, who had been using pagers as a way to evade Israel’s surveillance of cell phones. But the killed and maimed included children and others who were in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The attack raised many questions. Such as: Why did Israel launch it now? What strategic goal is it meant to serve? Will it succeed on those terms?

Given the fluid nature of the situation, we decided to leave the speculation to the professionals. We reached out to Paul Pillar, a non-resident fellow at the Quincy Institute and the former national intelligence officer for the Near East and South Asia—which means he led the analysis of those regions for the CIA and all other American intelligence agencies. Here is a lightly edited version of Pillar’s assessment, which he relayed to us by email:

It is analytically hazardous to try to attach specific strategic objectives to this Israeli action (and many other aggressive Israeli actions, for that matter). Israel’s actions have for months now been driven at least as much by Benjamin Netanyahu's personal motives for continuing and even escalating a war as by sound strategic reasons that are in the best interests of Israel. Another driver of Israeli behavior has been more emotive than strategic—involving a base of anti-Arab sentiment that was heightened into even more intense hatred against Arabs by the Hamas attack last October.

The sabotaging of the pagers and walkie-talkies obviously involved a big, sophisticated operation that had to have been planned long ago. Intervening events have changed Israel's circumstances significantly in the meantime. That makes it difficult to connect decisions made this week with whatever strategic considerations may have underlaid the original planning of the operation.

This is the sort of operation that can quickly be wasted if it is compromised before being completed. If Hezbollah had gotten wind of the sabotage, it would have discarded all those pagers and walkie-talkies before the day was out. Thus, one possible explanation for the timing is that Israel had been given reason to believe that Hezbollah was close to discovering the operation, so it was now or never regarding final implementation of the plan. (Sort of reminds me of when I was in the Army in Vietnam and my base came under a rocket attack just 90 minutes before the ceasefire went into effect in January 1973—the adversary may have thought it to be a shame to have carried all that ordnance down the Ho Chi Minh Trail and then not use it.)

Israel’s principal declared objective regarding the current confrontation with Hezbollah is to allow Israelis who had been evacuated from the north of the country to return to their homes. This week's act of terrorism does nothing to further that objective, whether or not it is a precursor to a full Israeli invasion of Lebanon. Hezbollah will not be deterred from cross-border attacks and now will feel even more obliged than before to respond with force.

Are you the kind of person who likes to point out that the United States is sometimes guilty of doing things that it criticizes other nations for doing? And have you, in the course of highlighting this discrepancy between words and deeds, been accused of practicing “whataboutism,” which is considered a grave breach of protocol in US foreign policy circles? Well, you now have this consolation: Whataboutism works!

Foreign states are “highly effective in undercutting US public support for foreign policy initiatives” when they point out American hypocrisy, argue Wilfred Chow and Dov Levin in Foreign Affairs. They have survey data to back them up.

The survey presented more than 2,500 Americans with an example of the US criticizing a foreign country for election interference or mistreatment of refugees. Respondents were asked whether they approved of Washington’s statement and whether they supported sanctioning the country involved. A randomly selected group of the respondents then answered the same question again after seeing a relevant “whataboutist” critique of the US from another nation.

The results were stark. Fifty-six percent of respondents approved of Washington’s statement when it was presented in isolation, but only 38 percent approved after reading the whataboutist retort. And support for sanctions dropped from 59 to 49 percent. A parallel survey conducted in Japan had similar results: 46 percent approved of the US statement in a vacuum, but that dropped to 29 percent after participants got the whataboutism treatment.

The findings held whether the critique came from a US ally or adversary. And special pleading didn’t dampen the effect: “The US government could not counter whataboutism by arguing that its misdeed had supposedly benevolent intentions, such as promoting democracy,” Chow and Levin write.

One thing that neutralized the power of whataboutism was time: If the seemingly hypocritical act was from a bygone era—like the beginning of the Cold War—then citing it had no effect.

The practical upshot of the study, say the authors, is that US policymakers should be more selective in how they critique foreign states. Citing misconduct that America is also guilty of can wind up drawing attention “away from other governments’ actions and toward Washington’s own bad behavior.”

Of course, another way to avoid the whataboutism trap is to avoid doing questionable stuff in the first place. “[T]he United States would be wise to avoid making unethical decisions in pursuit of narrow, short-term objectives,” Chow and Levin write.

And there’s another reason to practice what we preach. As NZN has previously noted, “whataboutism” is central to human morality. Challenging people who don’t behave in ways they expect others to behave—asking them to either admit they did wrong or persuasively explain why they deserved an exemption—is part of the process by which ethical principles are articulated, clarified, and enforced.

This enforcement can work in small communities or big ones—even planet-sized communities. Whataboutism can help uphold the norms and laws that would constitute a truly fair and functional “rules-based international order.” Which makes it ironic that so many people who profess to favor such an order also use the term “whataboutism” as a slur.

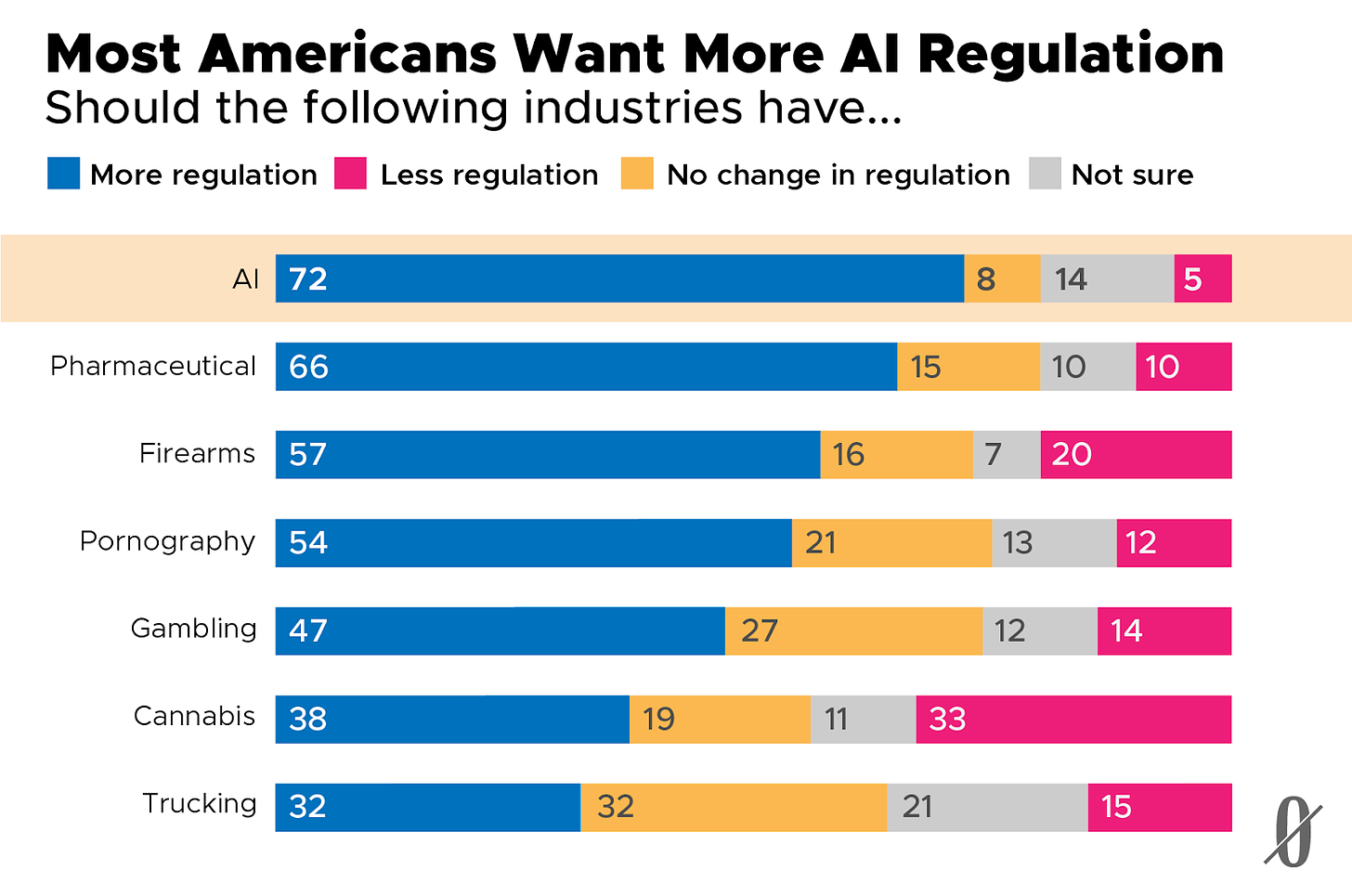

A new poll from YouGov found that 72 percent of Americans want more regulation of AI—a 15 point increase since the pollster asked the same question in February 2023.

Data from online YouGov poll of American adults. Graph adapted by Clark McGillis.