How the US media encourages Bibi’s dangerous brinksmanship

Plus: OpenAI’s purportedly scary tool, Israel’s AI-boosted bombings, surprising climate graph, LLMs vs. conspiracy theorists, and more!

"One can expect a direct hit on a central target in Israel or a serious incident in one of our embassies around the world. Sooner or later, this could lead to an all-out regional war for which Israel is not completely prepared. … Whoever decided on the assassination is playing with fire."

—Israeli Gen. Yitzhak Brik commenting on the consequences of Israel’s killing three Iranian generals in Syria this week

Had Israel’s air strikes on food aid workers in Gaza not dominated news from the Middle East this week, its air strikes on Iran’s diplomatic compound in Syria would have. The Syria strikes, which killed three Iranian generals, marked a sharp escalation in Israel’s conflict with Iran and led to complaints that Israel was recklessly—or even intentionally—raising the chances that the US will be drawn into a regional war.

On Tuesday, the day after the Syria strikes, the New York Times published a background piece by Steven Erlanger that seemed almost designed to counter such complaints.

After observing in the first paragraph that the Syria strikes constituted a “major escalation,” Erlanger asserted in the second paragraph that, nonetheless, Israel wasn’t trying to start a war with Iran. In the third paragraph he elaborated: “Instead, the strike is a vivid demonstration of the regional nature of the conflict as Israel tries to diminish and deter Iran’s allies and surrogates that threaten Israel’s security from every direction.”

After all, Erlanger went on to explain, “The Iranian officials who were killed Monday had been deeply engaged for decades in arming and guiding proxy forces in Gaza, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq and Yemen as part of Iran’s clearly stated effort to destabilize and even destroy the Jewish state.”

Had Erlanger run those passages by Bibi Netanyahu before publication, it’s unlikely that there would have been any suggested edits.

There’s nothing necessarily wrong with that. It’s the job of the New York Times to convey the perspective of major political actors, and Israel’s leader is a major political actor. But so is Iranian leader Ali Khamenei, and Erlanger’s piece follows in the long New York Times tradition—and the long American mainstream media tradition—of not illuminating the perspectives of Israel’s adversaries. Over the years, this asymmetry has had at least two kinds of bad effects:

1) It warps the understanding of Iran’s motivations and interests on the part of Americans, including American policy makers and other elites. This makes it harder for the US to use carrots and sticks wisely, in ways that could stabilize the Middle East.

2) It helps foster a climate in which Netanyahu feels comfortable taking the kind of risk he took with the Syria attack. He knows that, should Iran’s retaliation lead to outright war, the average American media consumer, steeped in Israel’s perspective, will likely take Israel’s side and not object to American military involvement.

To Erlanger’s credit, he does eventually get around to underscoring the dangers of Israel’s assertiveness. He writes: “Ralph Goff, a former senior CIA official who served in the Middle East, called Israel’s strike ‘incredibly reckless,’ adding that ‘the Israelis are writing checks that US CentCom forces will have to cash,’ referring to the US military’s Central Command.”

There are other parts of Erlanger’s piece, too, that Netanyahu would have edited out. That’s what makes the piece such a useful specimen. As with so much US media coverage of Israel, its bias is subtle, so subtle that the author himself is probably not aware of it. After all, he’s under the influence of the same cognitive biases that afflict the rest of us when we process information about those we see as allies and those we see as adversaries. And if these biases didn’t operate subtly, we wouldn’t call them biases.

There are two closely related biases at work here.

1) We play defense, they play offense. A well known human tendency (and a common ingredient in what international relations scholars call the “security dilemma”) is to read offensive motivation into what your adversaries see as their defensive behavior. For example, though Iran views Israel’s Syria strikes as offensive, Israel—as Erlanger painstakingly established in his Times piece—sees them as defensive.

And vice versa:

Israel, in making the case that the Syria strikes are defensive, says Iran’s arming of Hamas and Hezbollah is offensive, since both are intermittently in conflict with Israel (though US officials, as Erlanger notes, believe Iran didn’t know in advance about Hamas’s Oct. 7 attack). But Iran considers its arming of Hamas and Hezbollah an act of defense.

Since this Iranian view will surprise many consumers of American media, it’s worth spelling out. I did that in a piece I published six years ago in the Intercept called “How The New York Times Is Making War with Iran More Likely.” Discussing why Iran arms Israel’s enemies, I wrote:

[H]aving the capacity to inflict unacceptable damage on Jerusalem and Tel Aviv can be a way of keeping both Israel and the US from attacking Iran.

You may have trouble understanding why Iran would fear an unprovoked attack. Most Americans don’t think of their country as wantonly aggressive and most Israelis don’t think of their country that way, either. But Israel has repeatedly threatened to attack Iran—and eight years ago assassinated Iranian scientists on Iranian soil. And America, for its part, has repeatedly signaled that it reserves the right to bomb Iran and that it would stand by Israel in the case of war with Iran.

Against the backdrop of Iranian history—including America’s support for Iraq in the Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s, which produced hundreds of thousands of dead Iranians—it’s hardly surprising that Iran views both Israel and America as forces to be deterred; or that Iran sponsored anti-American Iraqi militias after a massive American military force invaded and occupied neighboring Iraq in 2003; or that when America and its allies armed Syrian rebels, thus turning a probably doomed insurrection into a full-scale civil war, Iran sent forces into Syria to save its longstanding ally, Bashar al-Assad’s regime, rather than see it toppled, possibly by pro-American forces.

In the Intercept piece, I referred readers to an essay in Foreign Affairs by Vali Nasr, then dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies in Washington, called “Iran Among the Ruins.” Nasr wrote that “the Israeli and US militaries pose clear and present dangers to Iran.” This threat, along with hostile Arab neighbors and other perceived threats, had given rise to Iran’s policy of “forward defense,” he wrote. “Although Iran’s rivals see the strategy of supporting nonstate military groups”—in Syria and Lebanon—“as an effort to export the revolution, the calculation behind it is utterly conventional.” Iran’s foreign policy, Nasr said, is driven by national interest more than revolutionary fervor and “is far more pragmatic than many in the West comprehend.”

2. Attribution error. As regular NZN readers know, I’ve long been on an attribution error awareness crusade. I wrote three years ago that, “If I had to pick only one scientific finding about how the human mind works and promulgate it in hopes of saving the world, I’d probably go with attribution error.”

Here is how attribution error works:

We have a tendency to attribute people’s behavior to disposition rather than situation. (“That guy is being rude to the checkout clerk because he’s a jerk, not because he had a bad day.”) But there are two big exceptions to this tendency: (1) If an enemy or rival does something good, we’re inclined to attribute the behavior to situation (rather than acknowledge some essential goodness in them). (2) If a friend or ally does something bad, we’re inclined to attribute the behavior to situation (rather than acknowledge some essential badness in them).

Thus, when Israel does something that seems bad, like launch a lethal strike on a diplomatic compound out of the blue, raising the chances of regional war, the New York Times hastens to explain the circumstances that motivated the strike: Israel is besieged by Iranian proxies. But when Iran does something that seems bad—like support proxies that besiege Israel—you’ll have to do a lot of combing through New York Times archives to find anyone saying that Iran feels besieged by the US and Israel. (It’s much faster to just read my Intercept piece.)

This goes not just for geopolitical calculation but for domestic political calculation. American media is full of coverage of the political pressures that impinge on Netanyahu (including Erlanger’s description of how political pressures encourage him to do crowd pleasing things like kill Iranian generals). But if you want to learn that Khamenei is under pressure from hardliners to respond more forcefully to Israel’s recent assassinations than he did to America’s assassination of Gen. Qasem Suleimani in 2020, you’ll have to read something other than the New York Times.

The MSM’s warping of our view of the perspectives of adversaries isn’t an Israel-specific problem. American media coverage of Ukraine and Russia has long been, if anything, even more unbalanced than its coverage of Israel and Iran. In fact, I’d argue that this imbalance is one reason the US didn’t pursue diplomatic options that might have prevented the Ukraine war—and did pursue policies, going back well more than a decade, that led Russia to see the US-Ukraine relationship as threatening. But it’s too late to change that. Whether it’s too late to constructively change our perception of Iran is something we may find out in the coming days. —RW

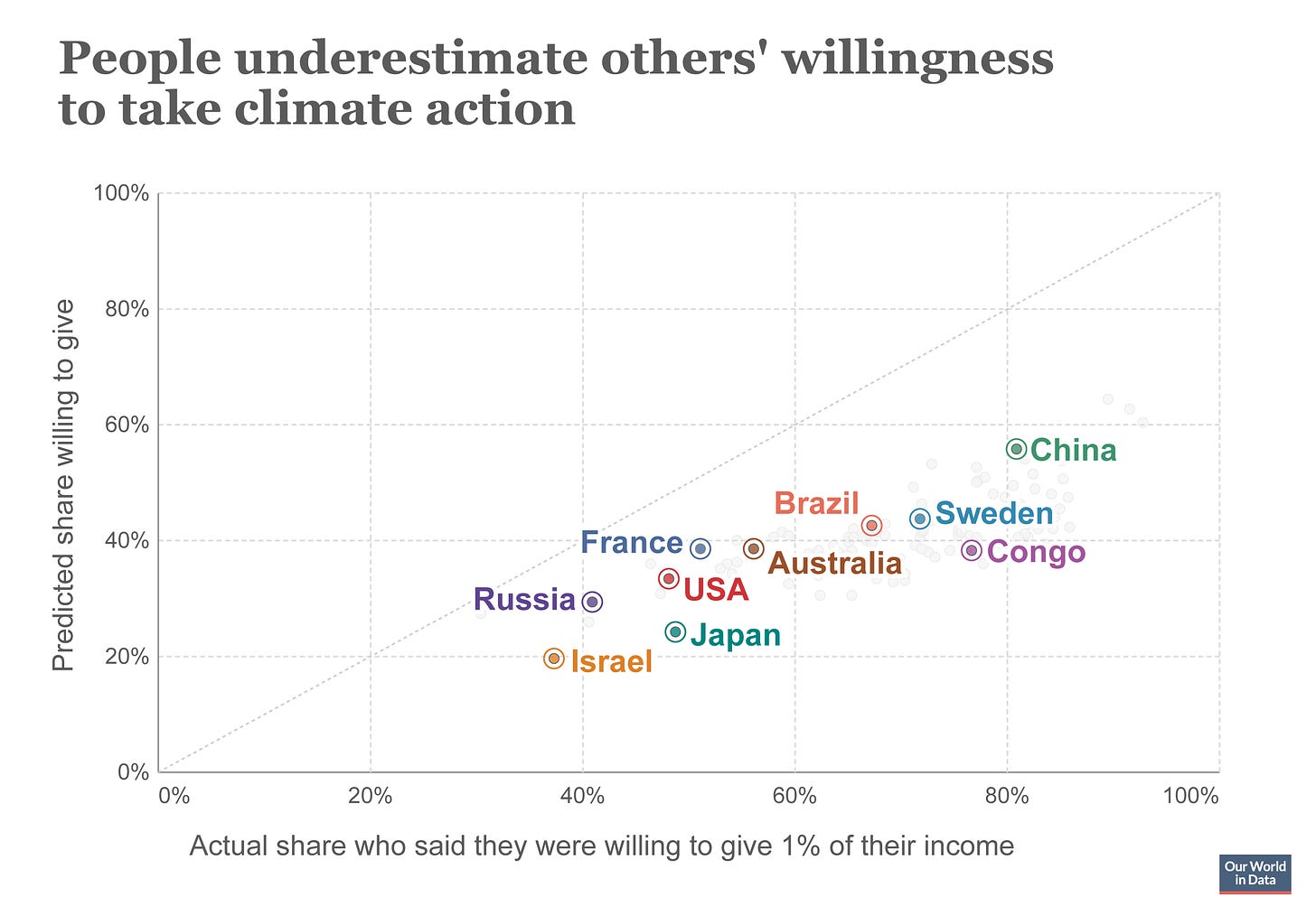

Do you ever lament that other people don’t care about climate change as much as you do? Good news: The problem is likely in your head.

The website Our World in Data highlights a recent study showing that people consistently underestimate the willingness of others to take climate action. In the graph below, the horizontal axis shows the percentage of people in various countries who said they’d be willing to sacrifice one percent of their income to combat climate change. The vertical axis shows the percentage of a country’s population that people in that country, on average, think would be willing to make this sacrifice. In all 125 countries polled, the average respondent guessed too low.

The Nonzero Podcast this week:

1. The economist Robin Hanson of George Mason University came on the pod to discuss AI risk, the backstory behind the formation of the “rationalist” community, and the “Great Filter”—an analytical framework he invented to help assess the implications of “the Fermi paradox” (the fact that there seem to be lots of habitable planets out there but no clear signs of extraterrestrial life). During the Overtime segment—available to NZN members—Bob argued that the lab leak explanation of Covid’s origins, whether true or not, illustrates the need for stronger international regulation of biotechnology. It was a tough sell, given Hanson’s libertarian, anti-regulatory leanings. Listeners can judge for themselves whether the sale was made.

2. Today, NZN aired one of our once-every-so-often podcast conversations with Derek Davison and Daniel Bessner, hosts of the American Prestige podcast. The discussion focused on the increasingly tragic and perilous situation in the Middle East and (relatedly) Biden’s increasingly perilous political situation. In Overtime, we discussed whether Trump would be more tolerant than Biden of a campaign by Israel to ethnically cleanse Gaza. NZN members can get a 20 percent discount on a subscription to American Prestige if they click the link at the very bottom of this issue of The Earthling.