Earthling: Is the new grim consensus on Ukraine really justified?

Plus: Out-of-control spyware, possible Pentagon pare-down, good environmental news, and more!

This week members of the Blob and their most persistent critics—the “restrainers”—found something they agree on: The Russia-Ukraine war will last a long time.

MIT professor Barry Posen—who literally wrote the book on US foreign policy restraint—argues in Foreign Affairs that the conflict “is turning into a war of attrition, a contest in which any gains by either side will come only at great cost.” Also in Foreign Affairs, Ivo Daalder and James Goldgeier—two esteemed members of America’s hawkishly inclined foreign policy establishment—write that “the war will grind on for the foreseeable future.”

And, like Posen, they don’t expect serious peace negotiations to start any time soon. As Posen puts it, both Russia and Ukraine are too “politically invested in the war” to pursue diplomacy.

But if you’re looking for signs that peace talks in 2023 aren’t entirely out of the question, we’re here to help! Two underreported data points suggest that political forces favoring negotiations may be stronger than they seem.

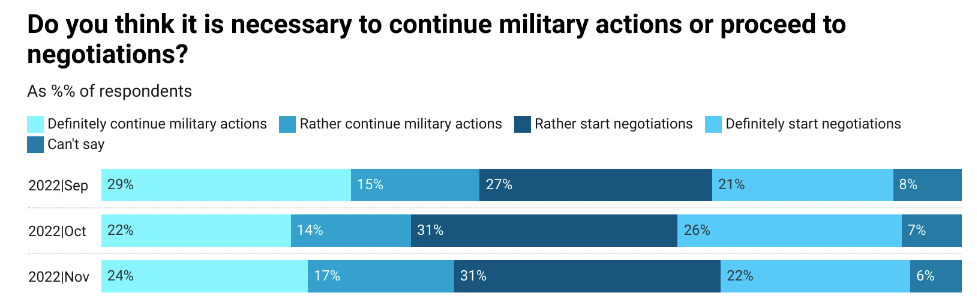

This week in an interview with Der Spiegel, Russian sociologist Lev Gudkov—who as head of the Levada Center runs the most respected surveys of Russian opinion—says that, though a majority of Russians profess support for the war, a majority also favor peace talks. Posed with the question, “Do you think it is necessary to continue military actions or proceed to negotiations,” 53 percent went with negotiations and 41 percent favored continued military action.

While this doesn’t mean Putin is under great political pressure to bring Russian troops home, it does suggest that he has political room for maneuvering should he decide that it makes sense to wind the war down. And various factors (including all the recent talk among US foreign policy elites about massively upgrading arms shipments to Ukraine) could push him in that direction.

Meanwhile, a poll released last month by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs (of which Daalder is president) found that 47 percent of Americans say the US should “urge Ukraine to settle for peace as soon as possible.” That’s up from 38 percent in July, and in that same period the percentage of Americans who say the US should support Ukraine “as long as it takes” dropped from 58 percent to 48 percent. Given that America has the leverage to push Ukraine toward peace talks (and then to give it various things that make a peace deal more appealing), this trend bears watching.

Of course, Ukrainians favor keeping up the fight until Russians are expelled from the country, including even Crimea, which Russia seized in 2014 and which has a heavily pro-Russia population. But this view has taken shape in a media environment that makes such an expulsion seem more doable, and less costly, than it would likely be. When the war started, all but one of Ukraine’s TV channels was shut down—and the one remaining channel conveys the government’s narrative, which (like the Russian government’s narrative, and pretty much every other government’s wartime narrative through world history) errs on the side of the upbeat. In other ways, too, the media environment, as shaped by the Ukrainian government, discourages talk of compromise.

The flip side of this coin is that the Ukrainian government has the power to recalibrate public expectations and aspirations and so build support for peace talks. But that will take time. How long it takes—and whether it happens at all—will depend in part on whether the US does something Posen recommends: use its influence to “reduce maximalist thinking” in Ukraine.

It’s been clear for some time that, realistically, meeting the climate change challenge will require both mitigation and adaptation—both reducing greenhouse gases to limit the rise in temperature and coping with the effects of what warming there is. This week the Guardian reported on a new experiment in adaptation: Within a few weeks a strain of wheat engineered to thrive in extreme heat will be planted in Spain on a trial basis.

Wheat provides 20 percent of the calories consumed by Earthlings. But a world with more and more heat waves and droughts could have trouble meeting that demand. So scientists have been trying to give wheat plants some of the properties of their hardier wild relatives.

That turned out to be hard, owing to a kind of built-in incest taboo—a gene that prevented wheat plants from exchanging chromosomes with those relatives. By identifying the gene—Zip4.5B—and creating a mutant version of it, scientists think they’ve finally cracked the code. When the harvest season rolls around, they’ll have a clearer idea of whether they’ve succeeded.

If you’ve read NZN for long, you’re aware that we’re inclined to deliver the occasional sermon on the power of cognitive empathy—that is, on how much good can come from understanding how other actors, whether friends or enemies or frenemies, view the world. In fact, if you started reading NZN only yesterday you may have a sense for that. And you may gather that we think cognitive empathy has especially critical application to geopolitics.

But geopolitics isn’t everything! Cognitive empathy also has application to everyday life, including relations with parents, children, and significant others. Yesterday I had a conversation about that with Josh Summers, a meditation teacher and podcaster. The conversation will be publicly available mid-next-week but is available to paid NZN subscribers now.

Kevin McCarthy, in securing the deal with the GOP’s Freedom Caucus that allowed him to become Speaker of the House, agreed to cap government spending at 2022 levels—which could force tens of billions of dollars in cuts to projected Pentagon budgets. Members of the Blob haven’t absorbed this news stoically.

The Washington Post gave this headline to an op-ed by Jennifer Rubin: