The memo that failed to prevent war

Why didn’t the Bush administration pay more attention to a warning about Ukraine issued in 2008?

Note: This is the first part of a tentatively envisioned chapter in the book I’m writing on cognitive empathy (whose tentatively envisioned introduction can be found here).

On February 1, 2008, William Burns, the US Ambassador to Russia, sent a memo that might have changed history but didn’t. The memo—distributed widely in the upper echelons of the George W. Bush administration—came two months before a momentous NATO meeting in Bucharest, Romania. There NATO’s member nations were going to decide whether to greenlight future NATO membership for Ukraine and Georgia—an idea that had a lot of support within the Bush administration but faced deep skepticism in Europe.

And it faced intense opposition in Russia—a fact that Burns’s memo was devoted to conveying and explaining. Burns wrote, among other things:

Ukraine and Georgia's NATO aspirations not only touch a raw nerve in Russia, they engender serious concerns about the consequences for stability in the region. Not only does Russia perceive encirclement, and efforts to undermine Russia's influence in the region, but it also fears unpredictable and uncontrolled consequences which would seriously affect Russian security interests. Experts tell us that Russia is particularly worried that the strong divisions in Ukraine over NATO membership, with much of the ethnic-Russian community against membership, could lead to a major split, involving violence or at worst, civil war.

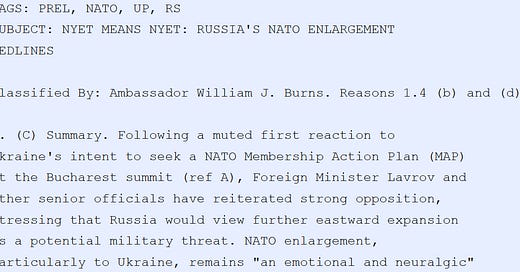

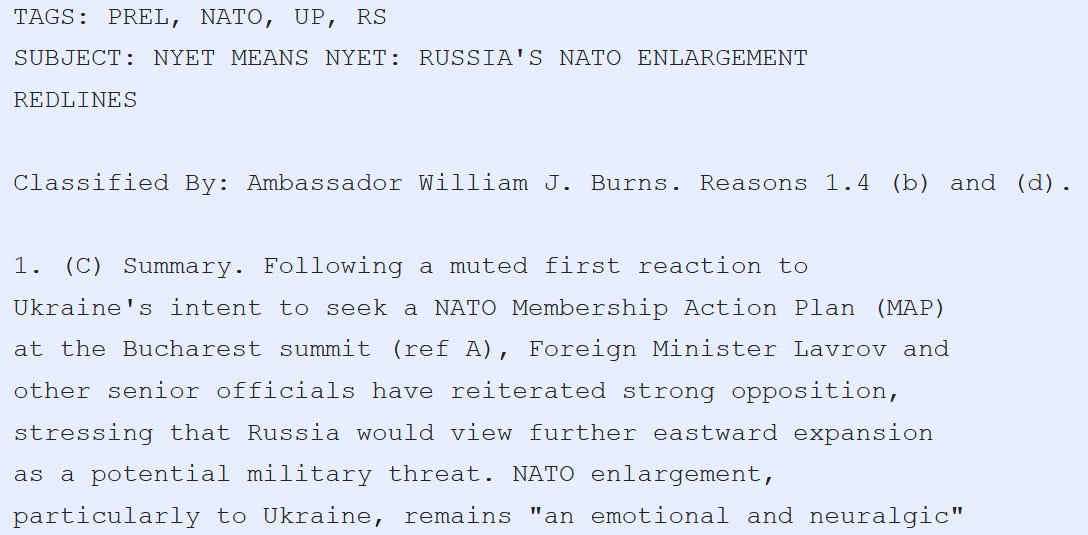

Burns gave the memo an emphatic title: “NYET MEANS NYET: RUSSIA’S NATO ENLARGEMENT REDLINES.”

To reinforce the message, Burns sent an email, cast in somewhat starker terms, to one of the memo’s most important recipients, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. He wrote: