Earthling: Nuclear warnings week

Plus: Poacher-hunting AI, Ukraine viewed from China, one weird trick to promote human rights, and more.

This week brought not one, not two, but three high-profile warnings about looming nuclear crises.

1) UN Secretary General António Guterres warned that “humanity is just one misunderstanding, one miscalculation away from nuclear annihilation.” He was speaking at a conference of nations that have signed the nuclear non-proliferation treaty (NPT) of 1968. Guterres noted multiple crises “with nuclear undertones,” not least Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

2) Rafael Grossi, director of the International Atomic Energy Agency, warned that Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant—the largest in Europe—is “completely out of control.” He urged Russia and Ukraine to allow experts into the plant to safeguard its nuclear material. Russia seized the plant in early March, but Ukrainian staff continue to operate it, leading to friction and dysfunction. “Every principle of nuclear safety has been violated” at Zaporizhzhia, Grossi said.

3) An Iranian spokesperson warned of “a decisive, firm, and immediate response” to new US sanctions that punish Tehran for enriching uranium beyond levels permitted under the 2015 nuclear deal (limits Tehran was respecting until President Trump abandoned the deal and reimposed sanctions). On Monday the US imposed sanctions on companies that have facilitated Iranian energy exports. Also Monday, Iran said it has the capacity to develop a nuclear bomb but doesn’t plan to do so. (For an assessment of the Biden administration’s failure to restore the nuclear deal, see this piece by Ryan Costello from June.)

Developing a bomb would violate the NPT, which Iran signed—but the treaty gives nations the option of exiting it with three-months notice. If Iran took that path, it would have the same status in international law as Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea—the only four nations known to have nuclear weapons aside from the five nations that already had them in 1968. Those five nations were allowed to keep their weapons, though the treaty commits them to disarmament over an unspecified time frame.

The US would do a much better job of promoting human rights abroad if it adopted a straightforward new policy: Do nothing! Or, at least: Do much less than it’s doing now. So argues Asli Bâli, Yale professor of international law, in a policy brief for the Quincy Institute. If the US truly wants to protect human rights, she says, it should quit thinking of coercion—military force and economic sanctions—as essential tools and should instead rely on diplomacy and example-setting.

When it comes to achieving humanitarian goals, Bâli contends, coercive measures do more harm than good. NATO’s intervention in Libya, for example, was justified on humanitarian grounds but resulted in “a radical increase in civilian deaths and injuries, a massive flow of weapons into the country and the eventual collapse of the state.” And as for sanctions: Ask impoverished people in Venezuela, Cuba, Afghanistan, and Syria whether they feel liberated by them.

On Monday, New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman made the case that Nancy Pelosi’s decision to visit Taiwan was “utterly reckless, dangerous and irresponsible.” His piece has gotten a lot of attention, partly because it was so scathing, but also because Friedman drew an easy-to-overlook connection between Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan and the Ukraine war.

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Friedman reports, Biden personally told Xi Jinping that giving military aid to Russia would endanger Chinese trade relations with the West. China seems to have withheld such aid—refusing, in particular, to supply Russia with drones it requested. Given the ease with which China could reverse this policy, now would seem to be a bad time to gratuitously antagonize the Chinese leadership.

The day after publishing that column, Friedman came onto the Nonzero podcast to talk about Pelosi, Taiwan, and Ukraine. During the hour-long conversation, he and I agreed that there was a second Ukraine-related reason to avoid needlessly worsening US-China relations: Russia, facing western sanctions, is now highly dependent on China, and China would therefore have unique leverage in pushing Russia toward a deal that ended the war.

You can watch that episode here or listen to it on the Robert Wright’s Nonzero podcast feed (not to be confused with the podcast feed for paid newsletter subscribers, which currently features a conversation with me, Jonah Goldberg, and Mickey Kaus that will go public next week. To set up that feed, paid subscribers can go to that episode, click “Listen on,” and follow the instructions).

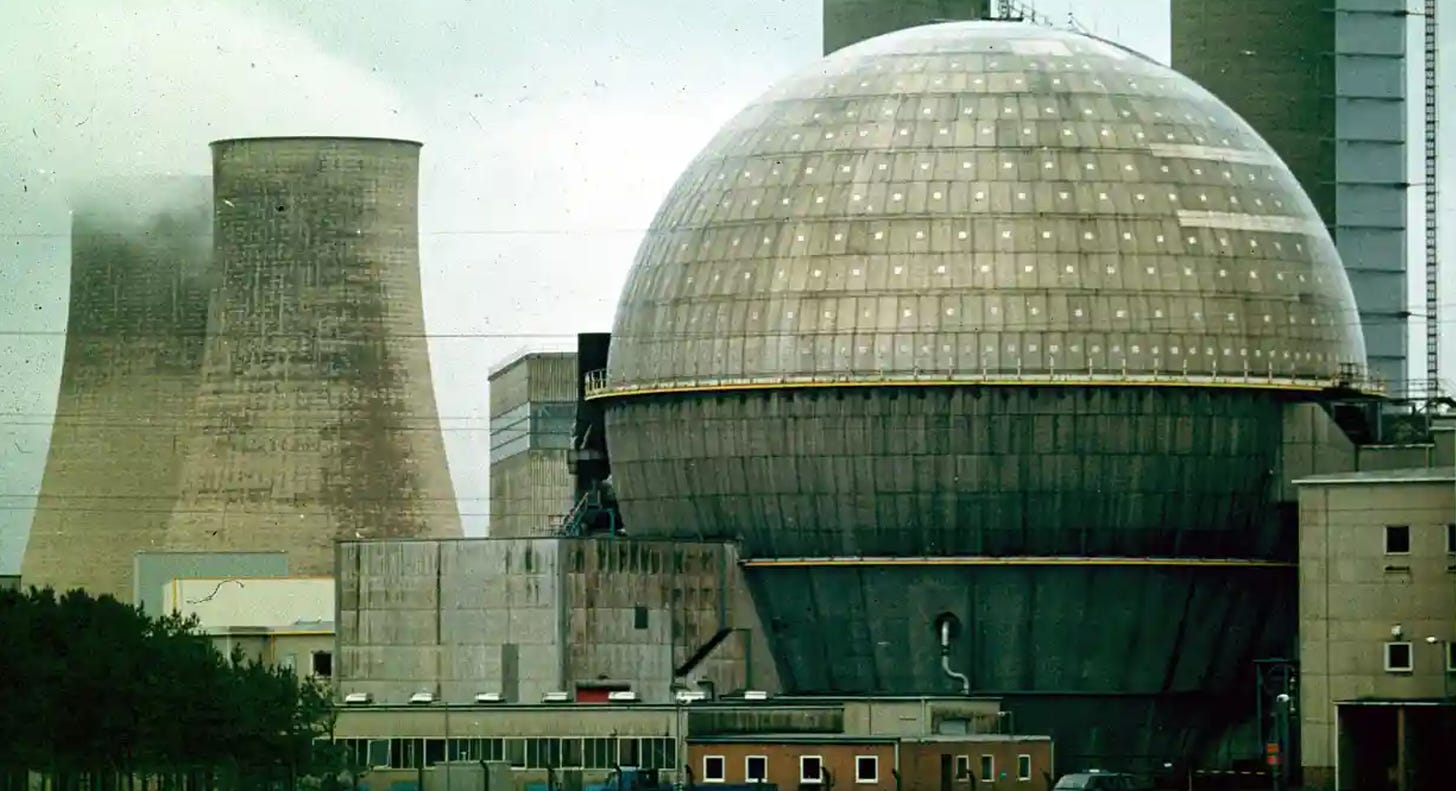

A year ago the UK unveiled a long-term plan for dealing with the world’s largest stockpile of untreated nuclear waste—bury it under the sea and throw away the key. This week it conducted “seismic surveys” to see if the bottom of the Irish Sea would be a suitable site.

The waste, which includes over 100 tons of plutonium, is located at a nuclear plant in northwestern England, where Britain’s nuclear weapons program kicked off in the late 1940s. The UK government is now looking to decommission the plant, which has seen numerous nuclear incidents, including the Windscale Fire of 1957—sometimes called “Britain’s Chernobyl.”

Critics of the new plan warned this week that, among other problems, it could create a nuclear nightmare for future Earthlings. The chair of an anti-nuclear group said the undersea location would make it hard to address a crisis that emerged before the waste finally (after scores of millennia) lost its radioactivity. He advocated moving the waste to a near-surface site where it could be more easily managed.