Earthling: Why do so many Chinese people like their government?

Plus: Itchy Twitter fingers, Ukraine diplomacy update, sperm drops everywhere, SBF and EA, and more!

President Biden and Chinese leader Xi Jinping, in their first face-to-face meeting since Biden became president, talked for three hours at this week’s G20 Summit. The meeting was hailed for its constructive tenor but was not without friction. Chinese state media report that Xi pushed back on Biden’s “democracy versus autocracy” narrative, asserting that “The United States has American-style democracy. China has Chinese-style democracy.”

An essay by Chinese political scientist Xiao Ma, published in Noema a few days before the meeting, sheds light on what Xi means by that. Local officials in China, Xiao writes, enjoy “considerable autonomy” in governing their jurisdictions, but they can only hope to rise in the government hierarchy if they “reach and balance goals such as promoting growth, attracting investment, preserving the environment and maintaining social stability.”

To get feedback about their performance, “the central government allows room for discussion on social media… Chinese netizens make all kinds of complaints about local officials on social media platforms such as WeChat, Weibo and Douyin, and scandals or misconduct that starts trending is often met with swift punishment.” Local officials are incentivized by the feedback to change unpopular policies, including, for example, policies that cause pollution. And popular policies are sometimes replicated in other localities.

Criticism of officials in Beijing is of course less likely to make it past social media censors than is criticism of local leaders. And, needless to say, China isn’t democratic in the sense of selecting its leaders by popular vote. Still, there is a kind of popular feedback that matters—it guides local officials in their governance and is monitored by the central government and sometimes acted on.

All of this helps explain what Xi meant by “Chinese-style democracy”—and also helps explain why a form of government that many Americans see as unbearably repressive has considerable popular support in China.

Tired of reading hot takes about Elon Musk’s bull-in-the-china-shop approach to owning Twitter? Good news: Now you can listen to one instead! Paid subscribers can get an audio version of “Elon’s (cognitive) empathy issue.” The essay was published in written form in NZN on November 2.

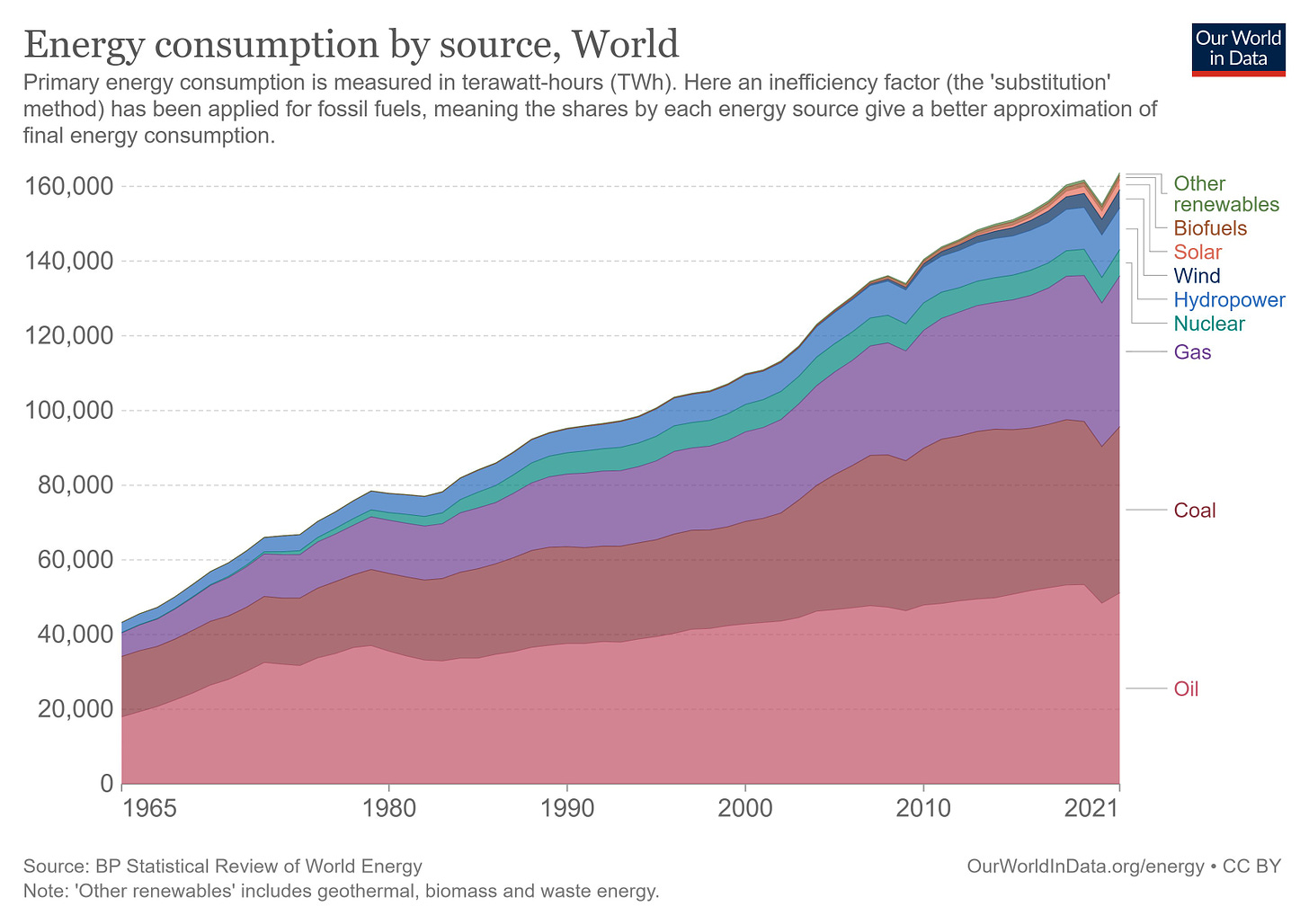

Last week’s Earthling featured an encouraging projection about future energy consumption that was based on an encouraging fact: the use of solar and wind energy has recently grown relative to the use of coal. But a close look at the graph conveying this fact would have revealed that even as coal use has declined in relative terms, it has continued to grow in absolute terms.

This week on Twitter, entrepreneur Arnaud Bertrand applied this distinction between relative and absolute decline to fossil fuels writ large, and showed why current trends aren’t cause for rampant optimism. Though fossil fuels today constitute a smaller percentage of consumed energy resources than they did thirty years ago, consumption of fossil fuels has increased by 64 percent.

In our tweet of the week tournament, a former diplomat competes against a current congressman to see who has the itchiest trigger finger when it comes to demanding new sanctions against a US adversary. But a well-known economist—by going way beyond sanctions and calling, in effect, for World War III—takes the prize.

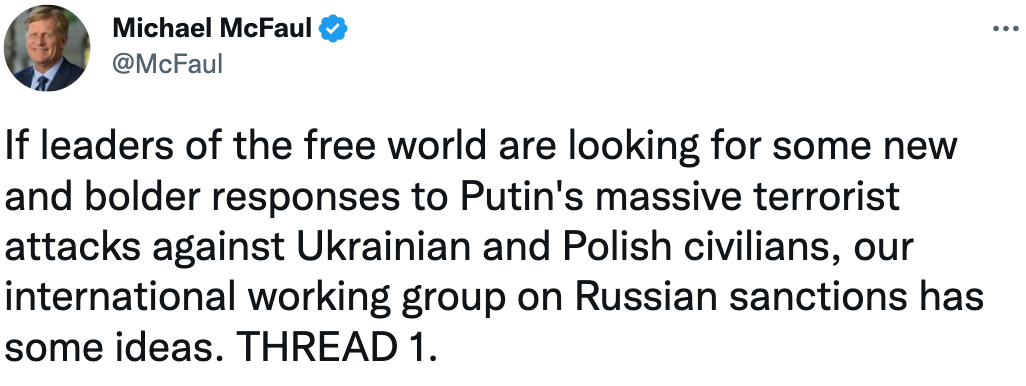

When news broke of an explosion in Poland near the Ukraine border, Michael McFaul—who served under President Obama as ambassador to Russia—was quick to blame the Kremlin.

The “new and bolder responses” included designating Russia a state sponsor of terrorism, seizing some of its assets, and imposing a bunch of new sanctions. Shortly after McFaul’s tweet, US and Polish officials said the explosion likely resulted from an errant Ukrainian missile.

Meanwhile, House Representative Ted Lieu was giving McFaul a run for his money. After Newsweek reported that Iran had sentenced 15,000 jailed protesters to death (an obviously dubious claim that Newsweek has now retracted), Lieu did some draconian sentencing of his own.

But the tweet of the week award goes to an influential economist for this doozy of a response to the Poland explosion story: