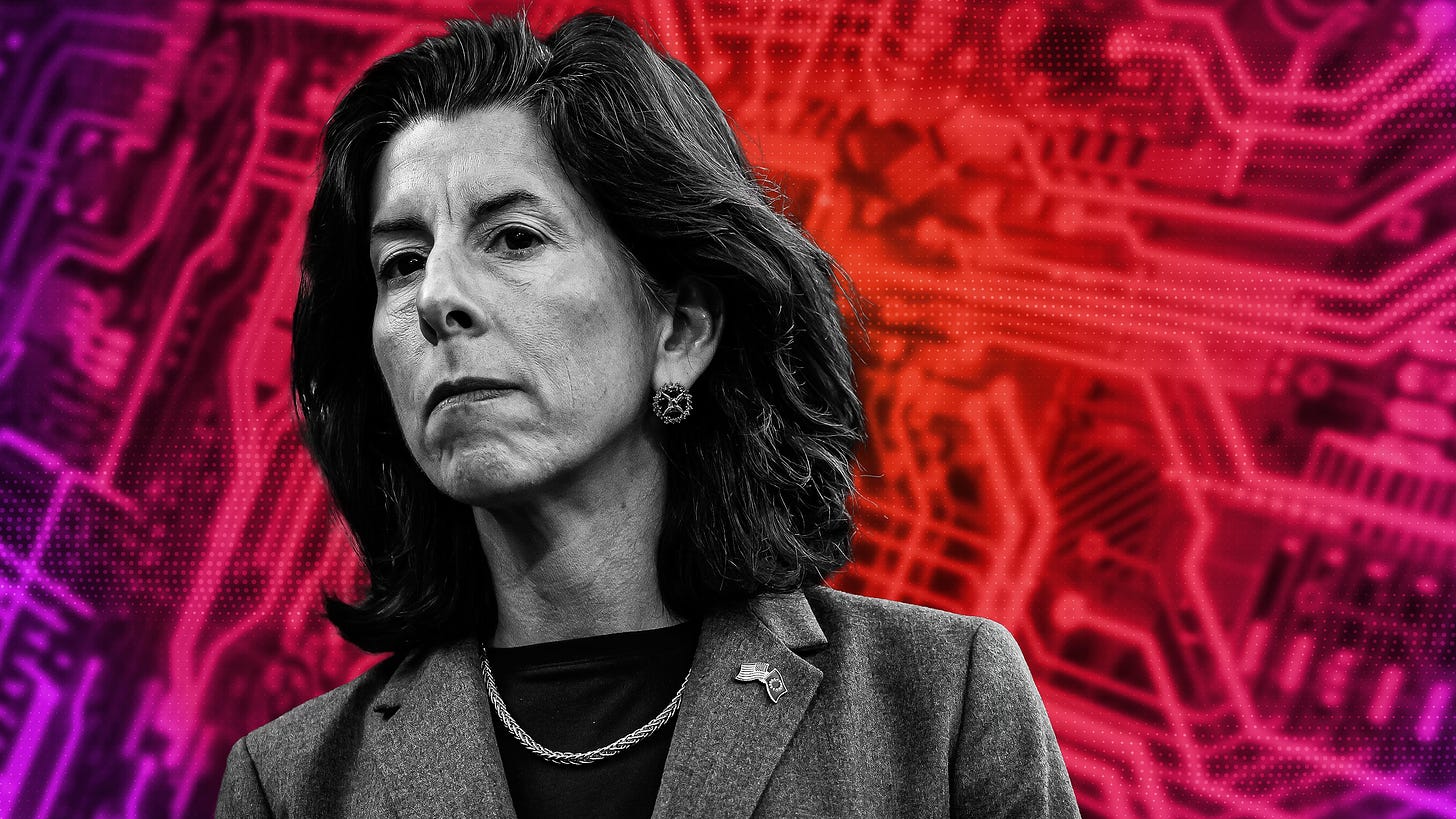

Has Biden’s Chip-War Chief Met Her Match?

Plus: The left’s Chernobyl syndrome. Kamala foreign policy watch. Time to ditch “genocide”? China’s outer-space disaster. Putting a lid on plastics. And more!

Note: The hardworking NonZero Newsletter team has received permission (from itself) to get some R&R as the Labor Day weekend approaches. So there won’t be an Earthling next Friday. But we’ll be back the following week, rested and ready, and indeed will roll out some new NZN features by the end of September. Enjoy the last week of summer!

In October of 2022, President Biden launched America’s “chip war,” imposing restrictions on China’s access to advanced semiconductors and the equipment needed to make them. The goal was to slow China’s progress in artificial intelligence, which the Biden administration had identified as a critical strategic asset. So, as the two-year anniversary of this Cold War II campaign approaches, how is it going?

Fine, according to Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, who oversees the policy. This week, Foreign Policy published a piece based on an extensive interview with the chip-warrior-in-chief, and in it she assures America that she’s fully engaged. She says that she’s “connected at the hip” with military and intelligence agencies and that Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin calls her his “battle buddy.”

Raimondo is aware that there are chip war skeptics who say Biden’s policy has spurred China to accelerate development of an indigenous chipmaking infrastructure. And she’s aware of evidence supporting this concern: The Chinese company Huawei surprised the world last year by putting a homemade 7-nanometer chip in its Mate 60 smartphone. But she says there are doubts about whether those chips can be produced at scale and argues that China continues to lag behind America in AI.

In the weeks since Foreign Policy interviewed Raimondo, though, Huawei has upped the ante again. The Wall Street Journal reports that the company will soon introduce a new AI chip—the Ascend 910C—that it says rivals industry leader Nvidia’s most powerful chip, the H100. If Huawei is right about that, its new chip will easily surpass the hobbled version of the H100 (the H20) that Biden allows Nvidia to sell to China. (Meanwhile, Nvidia’s next-generation AI chip, the B200, reportedly faces a delay of at least three months owing to a recently discovered design flaw.) The Journal piece observes that “Huawei’s ability to keep advancing in chips is the latest sign of how the company has managed to break through US-erected obstacles and develop Chinese alternatives to products made by the US and its allies.”

Elaboration on the sources of China’s progress comes from Paul Triolo of the Albright Stonebridge consulting group, who several months ago published an in-depth assessment of Biden’s chip war. In a recent episode of the Sinica podcast, Triolo explained that “before October 2022, when Chinese companies could buy the most advanced tools from US suppliers, Japanese suppliers and Dutch suppliers,” there was less incentive to develop Chinese toolmaking capabilities, and this fact “to some degree held back Chinese toolmakers.” But since Biden launched the chip war, “hundreds” of Chinese companies—“toolmakers, materials makers, design companies, EDA [electronic design automation] toolmakers”—have increased their coordination, with Huawei playing an orchestrating role.

The US war on Huawei predates its broader assault on China’s advanced chip industry. The Trump administration, in addition to barring Huawei hardware from America’s 5G network, muscled the company off of the Android smartphone platform. Huawei responded by developing its own smartphone operating system, and now, with China’s chipmaking capability growing, “Huawei has arguably come roaring back,” said Triolo. “The biggest losers are US toolmakers.”

Hurting American companies isn’t traditionally part of a commerce secretary’s portfolio. Then again, as Raimondo notes, “We’re at the red-hot center of national security and economic competitiveness. Some of that is because technology is in the middle of everything, and some of it, I think, is just the way in which I have managed this place.”

Triolo says China’s chipmaking infrastructure isn’t yet close to full recovery from the Biden assault. “In some sense, of course, the controls have been successful. But on the other hand they have massively incentivized China’s industry to try and overcome some of these bottlenecks.”

Meanwhile there are other costs of the Biden policy. It has caused tension with US allies whose tech companies are affected (and the resolution of those tensions sometimes dilutes the policy). And, because the policy prohibits Taiwan’s TSMC foundry—the most advanced chip factory in the world—from exporting high-end chips to China, China now has less to lose from starting a war with Taiwan. A war would almost certainly leave the TSMC factory enduringly incapacitated, which would still stop the flow of advanced chips to the West.

The Biden policy also steepens the already severe challenge of having a constructive dialogue with China about the international governance of AI, or even about the nurturing of international AI norms. And lots of analysts say that ultimately any effective governance of AI will have to be international—and will have to involve, in particular, the world’s two AI superpowers, the US and China.

Perhaps not coincidentally, Huawei released its Mate 60 while Raimondo was visiting China. And, much to Raimondo’s displeasure, someone made fake Mate 60 ads featuring a picture of her and put them on social media. “My kids sent me the [memes], saying ‘Mom, this is terrible!’ because it’s all over TikTok,” Raimondo told Foreign Policy. (She seems to say that she saw actual billboards in China with such ads, but fact checking by Radio Free Asia renders any such claim dubious.)

The US seems to be moving toward a further tightening of tech exports to China. Triolo says that’s in part because of pressure from Congress in the wake of Huawei’s successes and “in part because Secretary Raimondo was angry that Huawei released the Mate 60. So there’s some sort of payback here that’s coming. I call it the Huawei revenge rule.”

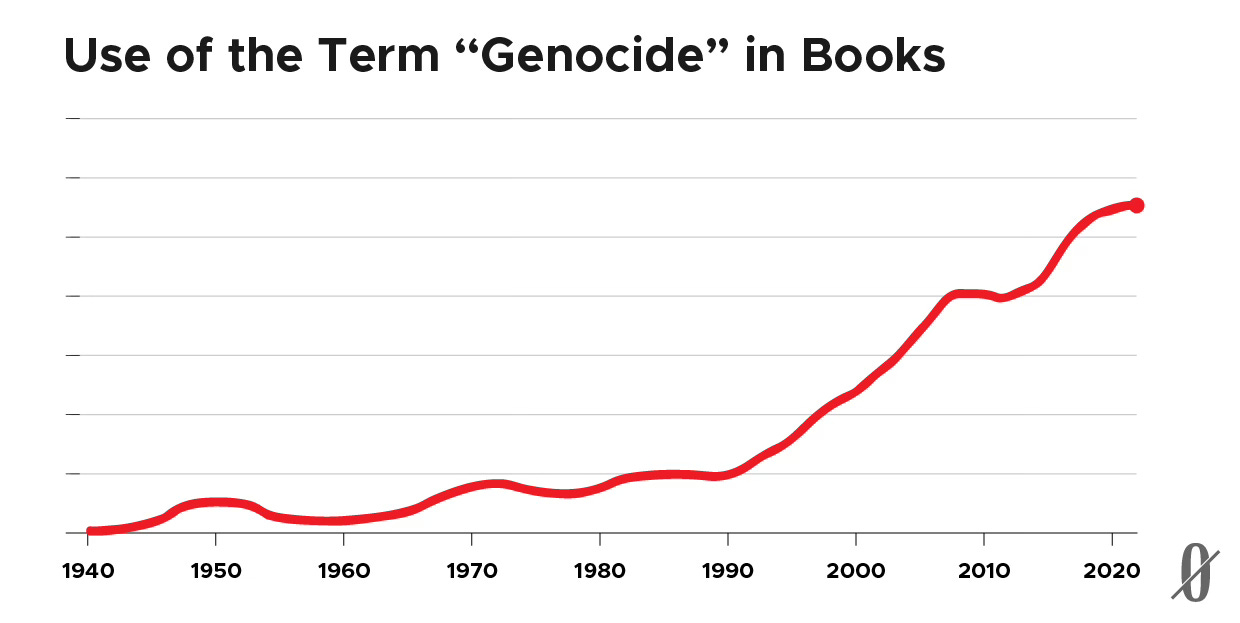

It’s time to ditch the word “genocide,” argues author and Boston Globe columnist Stephen Kinzer. He says the term is over-used and highly politicized—an “endlessly elastic code word for everything bad that happens in the world.”

Consider the contrasting positions of the US and South Africa on what constitutes genocide. The US says China is committing genocide against ethnic Uyghurs—in the form of forced assimilation and cultural erasure—but rejects the use of the term to describe Israel’s mass killing of Palestinians in Gaza. South Africa, meanwhile, brought a genocide case against Israel in the World Court but refrains from condemning China’s treatment of Uyghurs.

The term “genocide” dates back to the 1940s, when lawyer Rafael Lemkin coined it to capture the horrors of the Holocaust. Kinzer says the legal definition that grew out of Lemkin’s work is “breathtakingly broad,” encompassing even “mental harm” to members of an ethnic group.

And attempts at creating a narrower definition tend to run into problems of their own, Kinzer says. The Oxford definition of genocide is “the deliberate killing of a large number of people from a particular nation or ethnic group with the aim of destroying that nation or group.” But what, Kinzer asks, constitutes a “large number”?

Many still argue that the term, if lacking in precision, is useful: The Genocide Convention has empowered international courts to convict perpetrators of horrific war crimes in Rwanda, Bosnia, and elsewhere. So it may make sense to keep the term but find ways to tighten the definition.

NZN readers, you tell us:

PS: In 2021, Kinzer—author of the highly regarded book The Brothers, about Allen and John Foster Dulles—came on the NonZero podcast and discussed the Cold War, covert imperialism, and the CIA’s strange origin story. You can watch the conversation here.

Foreign policy “realism” is notorious these days, thanks largely to realist political scientist John Mearsheimer’s controversial theory that NATO expansion provoked Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

But what exactly is realism? What do the different schools of realism have in common? How much light does realism really shed on Ukraine or for that matter Gaza and other pressing issues? Is realism dark and amoral? Is realism really realistic? Is Mearsheimer’s version of realism overly simple, as critics have charged?

Glad you asked! Emma Ashford, an international relations scholar and promoter of “realist internationalism,” came on the NonZero podcast this week and discussed all those questions and more. You can watch or listen to the conversation—including the NZN-members-only Overtime segment—here. And if you want to share this content with family and friends, rate and review the podcast on your podcast app, smash the like button and subscribe to the Nonzero Channel on YouTube—well, that’d be ideal.

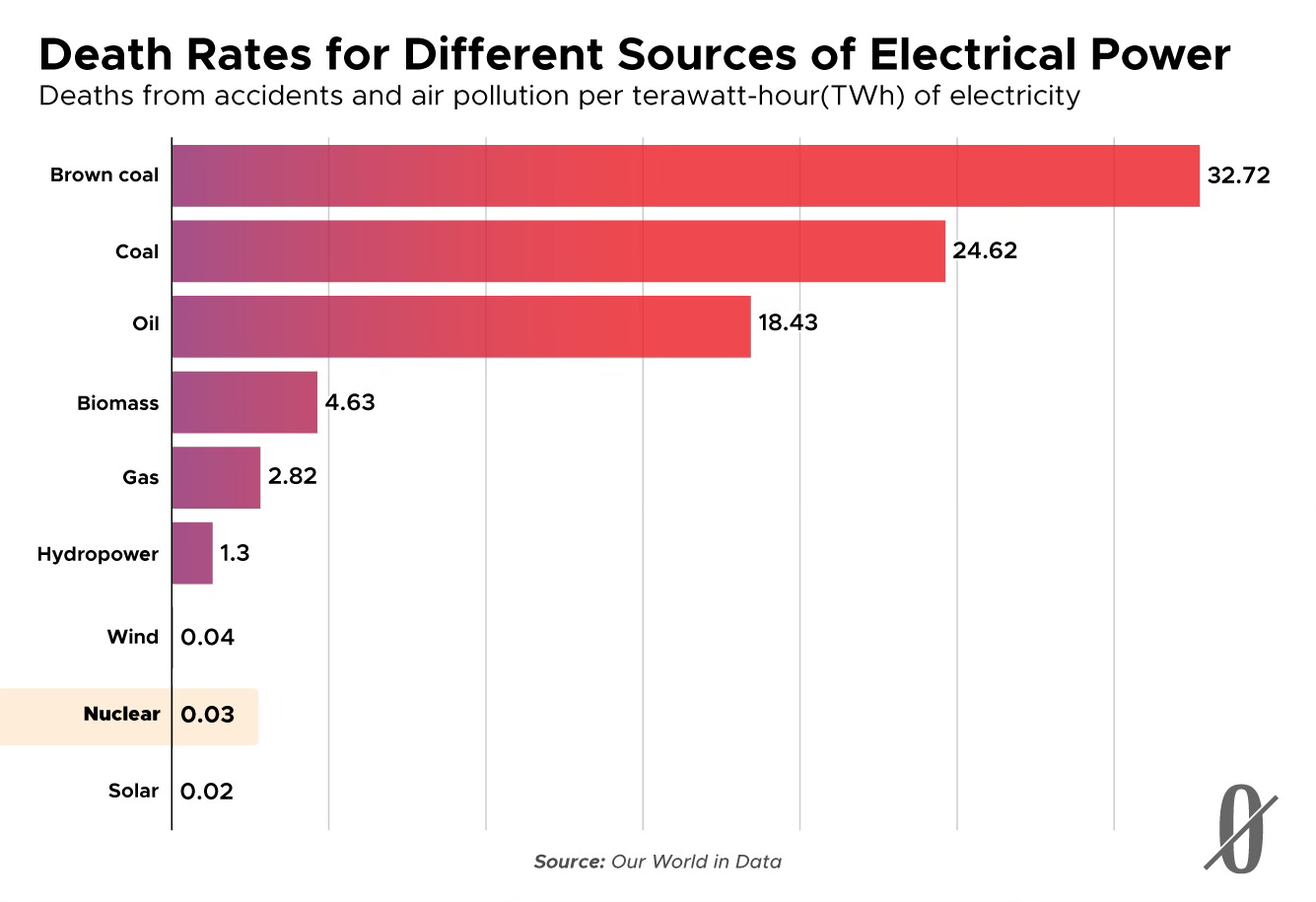

The left must get over its “irrational technophobia” and embrace nuclear energy if it’s serious about fighting climate change, writes Leigh Phillips in the socialist magazine Jacobin.

Phillips says nuclear power is far safer than most other types of electricity production, including some other forms of green energy.

Phillips homes in on the 1986 Chernobyl meltdown, history’s most famous nuclear power disaster. “The disaster was solely a product of a corrupt and dying Stalinist regime, not of the technology of nuclear energy itself,” he argues. “[B]laming the technology rather than Soviet autocracy is to let the latter off the hook.”

Phillips concedes that nuclear energy comes with a certain level of risk and poses the challenge of waste disposal. But he says that both problems are overstated and that, in order to rapidly scale up green energy and beat back climate change, we must accept the “unavoidability of health and environmental trade-offs.”

Over the past few weeks, NZN has offered a number of reasons to think a Kamala Harris administration would bring a relatively dovish approach to foreign policy. This week brought more signs of hope for people in the foreign policy “restraint” community—but also some cause for concern.

First some of the good news: