Is Elon Our First True Oligarch?

Plus: Michael McFail, red-blue crime divide, election waiting game, America’s changing tribes, China rides Meta’s Llama, and more!

Note: The NonZero Newsletter team will host an election night thread on NZN Chat starting around 8 p.m. Eastern Time on Tuesday. We hope you’ll join us for a discussion full of NZN-inspired news, analysis and commiseration.

This week in The Adventures of Elon:

Twitter—okay, okay, “X”—suspended the Hebrew-language account of Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. The account had existed for one day and had only two posts. The first was an innocuous quote from the Quran, and the second was a response to Israel’s attack on Iran over the past weekend: “Zionists are making a miscalculation with respect to Iran. They don't know Iran. They still haven't been able to correctly understand the power, initiative, and determination of the Iranian people.”

X didn’t provide a reason for the suspension, and the post didn’t seem to violate the site’s rules. It didn’t say there would be a violent retaliation for the Israeli attack—indeed, some analysts took it as a sign that there wouldn’t be. Meanwhile, among the posts that can still be found on X is this one from Israeli National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir: “As long as Hamas does not release the hostages in its hands—the only thing that needs to enter Gaza are hundreds of tons of explosives from the Air Force, not an ounce of humanitarian aid.” That would seem to be a threat to commit the war crime of collective punishment, and it has remained on X for over a year.

How to explain this discrepancy?

Theory number one: Musk is still atoning for a post of his that last year got him accused (not implausibly) of anti-Semitism. One accuser, the Anti-Defamation League, had reconciled with Musk after he banned tweets containing phrases like “from the river to the sea”—a rapprochement that led Isaac Chotiner of the New Yorker to complain that the ADL will commend people who only yesterday endorsed “vile neo-Nazi anti-Semitism” so long as today they “take a strong stand against critics of Israel.” Well, Khamenei certainly qualifies as a critic of Israel, and deleting his social media account is a fairly strong stand.

Theory number two: Musk deleted Khamenei’s account to please his new best friend, Donald Trump. Trump has a close relationship with hardline pro-Israel donors, who tend to be Iran hawks, and he has depicted his relationship with some of them as flatly transactional. This year he described how billionaire couple Sheldon and Miriam Adelson “would come into the White House probably almost more than anybody, outside of people that worked there,” and “as soon as I’d give them something—always for Israel—they’d want something else.” Trump didn’t list the things they’d asked for. But Iran is known to be of interest to them (Sheldon once seriously proposed dropping a nuclear warhead on Iran—“in the middle of the desert,” just to show that “we mean business”), and President Trump certainly took his share of anti-Iran initiatives. He withdrew from the Iran nuclear nuclear deal, imposed a boatload of sanctions, and ordered the assassination of Iran’s most important military commander (in violation of international law). Sheldon has died since Trump left office, but his widow gave $100 million to a pro-Trump super PAC this year.

Whether or not Musk had Trump on his mind when he greenlighted the suspension of Khamenei’s account, there’s no doubt that he’s willing to use his social media platform to do Trump’s bidding. In September, X suspended the account of independent journalist Ken Klippenstein after Klippenstein posted a story based on a leaked Trump campaign document about the political liabilities of prospective running mate J.D. Vance. That suspension, subsequent reporting revealed, came at the behest of Trump’s team. (X reinstated Klippenstein’s account following backlash, but it’s still impossible to post links to the offending story.)

The support Musk gives to Trump’s candidacy goes well beyond jettisoning the free speech values he claimed were his motivation for buying Twitter in 2022. He has outdone Miriam Adelson in financial support, donating at least $119 million to the Trump cause in recent months. And he has unleashed his entrepreneurial creativity, launching a novel campaign scheme that involves giving money to voters (in possible violation of the law). Plus, his energetic entry into the Trump campaign has no doubt activated legions of Musk fanboys who might otherwise have lacked the motivation to vote.

All told, Musk may well have done more for an American presidential candidacy than any capitalist in the history of American capitalism. And it looks like he can expect to be well compensated if his effort succeeds. Trump has vowed to make him head of a new “government efficiency commission” that would recommend budget cuts and hold sway over regulators. Such a perch could allow Musk to take aim at the myriad government agencies that he claims have unfairly targeted his companies with investigations and regulatory scrutiny. And, whether or not these efforts prevailed over the inevitable bureaucratic and judicial pushback, Musk could certainly count on this much from a Trump presidency: Government contracts will flow to Musk’s various enterprises at least as abundantly as they’ve been flowing, and regulatory scrutiny of these enterprises will wane.

Meanwhile, you can expect Trump to have ideas about which domestic political actors, and which foreign political actors, should and shouldn’t have their content flowing freely on X. Whether or not the Khamenei case was an example of Trump’s influence reaching overseas, there would almost certainly be comparable examples in a second Trump term.

The corruption of American politics by rich and powerful people is nothing new. But the problem has gotten worse in recent decades, exacerbated by such things as the Citizens United Supreme Court Ruling in 2010, the McCutcheon v. FEC ruling of 2014, the growing use of super PACS to skirt limits on direct campaign contributions, and the growing concentration of wealth in America.

There’s a self-reinforcing cycle here: The more concentrated wealth becomes, the more political power a small number of super-rich people have—and this power translates into policies that further concentrate wealth. Trump has talked about enacting a variety of tax policies rich people would love, and he says he’ll impose tariffs of at least 10 percent on all imports, which would amount to a de facto consumption tax that would disproportionately hurt low-and middle-income people.

Democrats, too, are increasingly beholden to rich donors, which helps explain why Kamala Harris has scaled back Biden’s plan for a wealth tax. The positive-feedback cycle that is concentrating political power in the hands of fewer and fewer Americans is a bipartisan structural problem, not an Elon Musk problem.

That said, Musk is far and away the most dramatic example of concentrated power. By virtue of his undeniable intelligence, creativity, and drive, he has wound up with an impressively diverse portfolio of influence. The US government is dependent on SpaceX launch capabilities, and lots of actors around the world, including the Ukrainian army, are dependent on SpaceX’s Starlink internet infrastructure. Recently, in his role as chief of X, Musk refused to remove content that the Brazilian supreme court had deemed illegal—and then, when a Brazilian judge reacted by ordering internet access providers to pull the plug on Brazil’s X, Musk put on his Starlink hat and refused to do that, too. (He eventually relented.)

It’s hard to say when exactly a country crosses the line from plutocracy (government that’s deeply influenced by the rich broadly) to oligarchy (government that’s deeply influenced by a small number of potentates whose power may derive not just from money but from other resources—like social media companies and aerospace companies). But when a single individual can exert as much influence over a presidential campaign as Elon Musk is exerting, and can use diverse assets to do that, you’re definitely moving in the direction of oligarchy. And when that individual stands to be rewarded as handsomely as Musk would be rewarded in a Trump presidency—even given a whole new form of overt political power, as Trump has promised—you’re moving pretty briskly in that direction.

Does America face a growing crime problem? If your answer to that question is “no,” there’s a good chance you’re a Democrat.

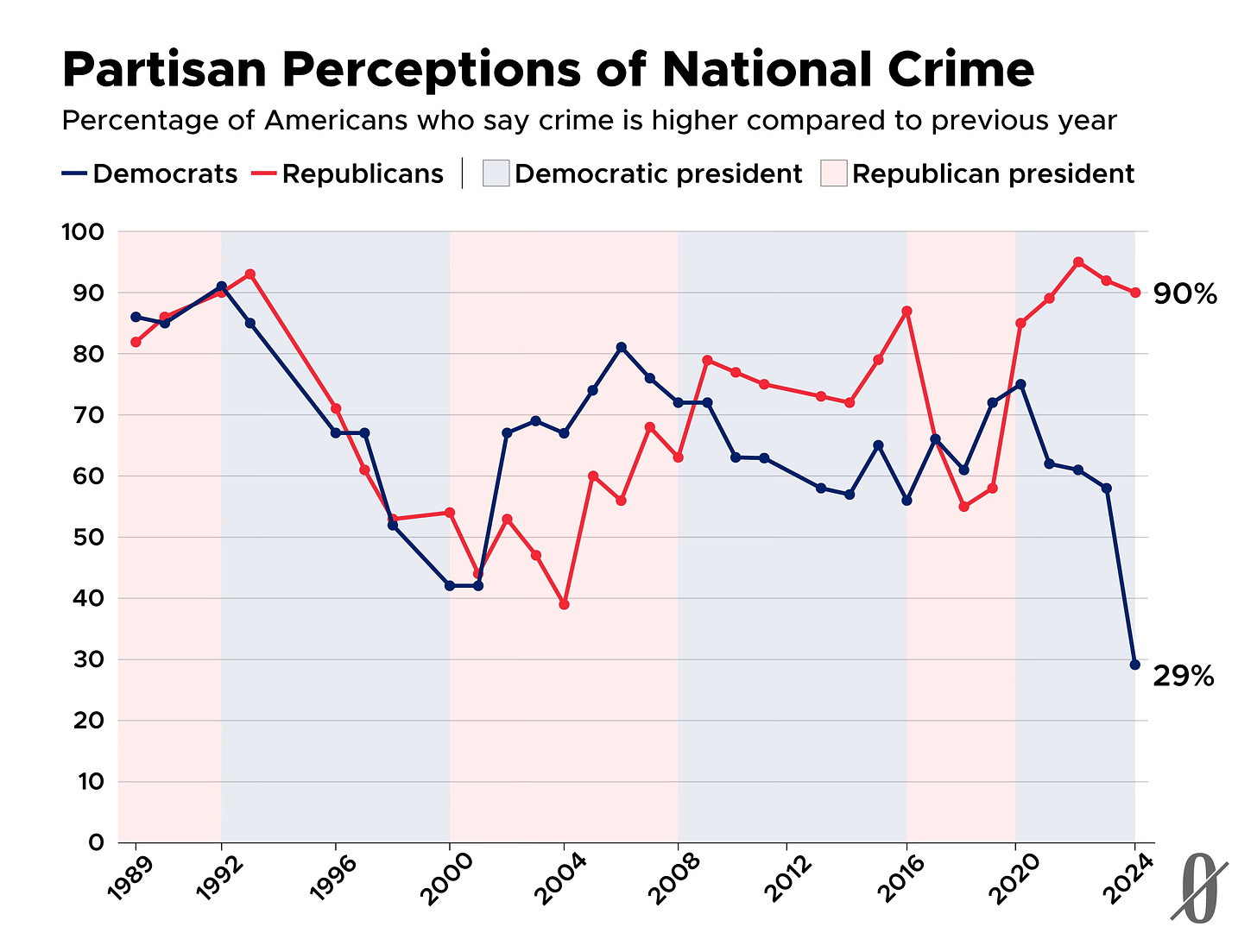

A new poll from Gallup asked Americans whether the country is experiencing more crime today than a year ago. Ninety percent of Republicans, but only 29 percent of Democrats, said “yes.” That’s the biggest discrepancy since Gallup started asking the question in the late 1980s.

Of course, people in different places and different socioeconomic strata and of different ethnicities may face different circumstances—including different levels of nearby crime. And all these factors also correlate with party affiliation. So this red-blue gap may not be a straightforward example of how differences in partisan perspective—and attendant differences in media and social media diet—can influence perceptions. But when the gap is this big, it’s bound to be at least partly an example of that.

This week the NonZero podcast aired a conversation with author and journalist Peter Hessler about his new book Other Rivers: A Chinese Education. Hessler, who taught college English in China in the 1990s, returned there in 2019 to teach a new generation of students—and to gain insights into the country’s radical transformation over the past two decades. Early in the episode, Bob asked Hessler what Americans get wrong about the rising superpower. A (lightly edited) excerpt from that part of the conversation is below:

Bob: Do you have a list of common misconceptions on the part of Americans about China or about the way the world is viewed by Chinese or America is viewed by Chinese?

Peter: The political system is a big one. There is a sense [among Americans] that China is a very repressive state and that the party controls everything. And I think when you live there, you see that there are all kinds of holes in the bureaucracy. There's much more chaos on the ground. It's not Orwellian necessarily.

One of the guys I talked to in this book, an academic who studies China and grassroots political movements, had a friend who had asked him, "Is it more like Kafka or is it more like Orwell?" And he said, "I think it's probably still a little more like Kafka."

Now, there are definitely moments that are Orwellian, but it's not as if the party knows everything that's going on. A lot of times it does feel like Kafka...

So, I think that's something that Americans often get wrong. I mean, we tend to view it as this really monolithic state, and that all the people are just hopelessly repressed and have no idea what's going on.

Bob: Although, speaking of Orwell, on the one hand Orwell's books were tolerated and you were allowed to teach Animal Farm, but, on the other hand, in your classroom there was a camera, right? And for all you knew, at any given time you were being monitored. I hope this isn't a plot spoiler, but you ultimately got into a certain amount of quasi-political trouble yourself…

This led to your leaving a little earlier than you would have liked. You would have liked to teach another year there on the second round of teaching, right? But the university felt the political heat and said sayonara.

You can watch or listen to the episode, including the members-only Overtime segment, here.

The 2020 presidential election brought a distinctive source of stress: Major news outlets took four days to declare a winner—the longest such gap since the contested 2000 election.

Could something like that happen again next week? The 2020 delay was largely a product of the unprecedentedly big mail-in vote. Mailed ballots take longer to count than in-person votes, and the hard-to-predict gap between Democratic and Republican propensities to vote by mail made extrapolating from the in-person vote perilous.

This year, according to NBC News, reforms that will expedite vote-counting in some swing states, including Pennsylvania and Michigan, may allow us to see key results as early as Wednesday morning. But the likely closeness of the contest could still lead to delays. Poll-based election models suggest that the outcome in some swing states could come down to a few thousand votes, making projections prohibitively hard.

To help us see through all this fog—or at least help us guess when the fog will lift—we turn to the NonZero braintrust with this week’s Metaculus question: Will at least three of the five major TV networks call the election by this Wednesday at noon US Eastern Time? (For purposes of this question, the major networks are NBC, ABC, CBS, Fox News, and CNN.) As a reminder: Metaculus is a platform that aggregates forecasts about various events, and we’re hoping to use it as a way to sharpen our predictions and test our assumptions about the world. Make sure to submit your forecast by Monday night, when we’ll close the question and commence holding our breath.

PS: As it happens, election night will provide the answer to at least one of our previous Metaculus questions. NZN readers gave only a 15 percent chance that Israel would strike Iran’s nuclear facilities before the election, and the evidence suggests that this skepticism will be vindicated. Meanwhile, readers gave a five percent chance that Trump would concede if he loses. If 538’s model is correct, we’ll have a 50-50 shot of testing that proposition.

After the Soviet Union dissolved and the Cold War ended, both US and Russian officials hoped for increased cooperation between their countries. So why did US-Russia engagement fail to click?