Is Trump a Peacenik?

Plus: Kamala (and world) confront gender divide, “safe” superhuman AI, America’s China election, Ukraine’s survival prospects, and climate coping technology.

Donald Trump, in an interview this week with podcaster Lex Fridman, sounded a warning: President Biden (and, not incidentally, Vice President Harris) are leading America toward World War III. Conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East, and rising tensions in China’s neighborhood, could boil over into a global conflagration—unless, Trump said, he’s elected president in November.

This theme—that the Biden administration is responsible for starting or sustaining conflicts that a President Trump would have prevented or ended—has become the heart of Trump’s national security message on the campaign trail. He says he'll “end the endless foreign wars” and smooth America’s foreign relations.

Trump struck a similar tone during the 2016 campaign. He declared war on the traditionally dominant warmongering wing of his party and promised to end America’s costly and energy-sapping military entanglements. Do the subsequent four years—Trump’s record as president—support his continued depiction of himself as a force for peace?

Daniel Larison, writing in his newsletter Eunomia, answers in the negative:

Trump had many opportunities to end wars when he was president, but he didn’t do it. Instead of ending them, Trump escalated every war he inherited. He sent more troops to Afghanistan. He loosened rules of engagement for US strikes. He ramped up the drone war. He increased support for the Saudi coalition while it was slaughtering Yemeni civilians. He also refused to end US involvement in the war on Yemen when Congress demanded it.”

To be fair, President Trump did commit the US to withdrawing troops from Afghanistan—and he even tried, every once in a while, to actually withdraw them. But it was Biden who fulfilled that commitment.

Trump is trying to turn this feat against Biden big time. He not only attacks Biden’s handling of the withdrawal—which, indeed, went awry and resulted in the deaths of thirteen US troops—but says this episode emboldened Vladimir Putin to invade Ukraine and Hamas to attack Israel.

But as Bill Scher of the Washington Monthly notes, troop withdrawals are usually messy and often bloody, and both Putin and Hamas seem to have conceived their military plans before America left Afghanistan. Hamas’s leadership in Gaza reportedly greenlighted a well-developed version of its plan three months before the August 2021 withdrawal.

And, actually, if you’re looking for an American president whose policies encouraged that greenlighting, Trump is certainly in the running. While western analysts posit various factors that may have convinced Hamas to launch the Oct. 7 attacks, the most commonly cited US policy is Trump’s Abraham Accords. In securing diplomatic recognition of Israel from Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates, Trump began the process of normalizing relations between Israel and Arab nations—and such normalization had long been considered the prize Israel would get only after it solved the Palestinian problem, presumably by giving the Palestinians a state. Trump, in trying to give Israel the prize prematurely, was taking away the most powerful non-violent geopolitical lever available to the Palestinians.

As it happens, Biden continued the drive for Arab-Israeli normalization. And, like Trump, he basically ignored Palestinian interests. (To get Saudi-Israeli normalization, Biden’s big goal, Bibi Netanyahu would have had to pledge to pursue a two-state solution, but only the most naive observers could have expected him to follow through.) So if indeed, as many observers believe, ongoing Arab-Israeli normalization loomed large in the strategic calculus of Hamas, Trump and Biden can share the responsibility for that.

The origins of the Ukraine War, too, carry a kind of bipartisan stamp. As CIA director Bill Burns once remarked, Putin’s motivation for invading seems to have had less to do with “Ukraine in NATO”—a distant prospect, as Putin knew—than with “NATO in Ukraine.” Putin (as his big pre-invasion speech made clear) was concerned about a kind of de facto NATOization of Ukraine—which included various forms of NATO-Ukrainian coordination and a growing flow of NATO weapons into Ukraine. Much of this happened on Biden’s watch, but Trump in one sense got the ball rolling; he was the first US president to authorize sending lethal weapons to Ukraine.

The spirit of bipartisan cooperation exhibited by Trump and Biden in their fomenting of conflict and tension extends even further—into the worsening of US-China relations. Trump launched not only a tariff war, but a tech war, trying to cripple Chinese tech giant Huawei. Biden sustained the tariff war and amped up the tech war, sharply restricting China’s access to advanced microchips and chipmaking equipment. As NZN reported two weeks ago, America’s tech war on China has met with, at best, mixed success—and in important respects seems to have backfired.

So what claims can Trump accurately make about his credentials for lessening global tensions and tamping down or preventing wars? Well, he can say that they don’t look much worse than Biden’s.

And even there the word “much” is doing a lot of work. Trump’s assassination of Iranian military commander Qasem Soleimani evinced a degree of recklessness that Biden hasn’t matched, and elicited an Iranian retaliatory strike that injured dozens of US soldiers and could well have started a major war. Trump also, of course, pulled the US out of the Iranian nuclear deal, something Biden wouldn’t have done. This soured relations with Iran, strengthened hardliners within Iran, and strengthened Israel’s incentive to start a war with Iran.

Trump’s Iran policies may reflect his well-known eagerness to accommodate even the looniest of uber-hawkish pro-Israel donors (an eagerness that seems to be paying off in this election cycle as it did in the last one). Joe Biden has drawn criticism for refusing to make a forceful attempt to get Bibi Netanyahu to end the killing in Gaza, but if Trump takes office in January, he’ll make Biden look pro-Palestinian by comparison. Trump says Israel should “finish the job” in Gaza, and Larison plausibly calls that “a greenlight for massacres and ethnic cleansing.”

Trump may be right in saying that Biden has brought the world closer to World War III. But if so, that’s partly because Biden has sustained, and in some cases intensified, Trump-era policies. Of course, that observation wouldn’t make a very effective element in a Republican campaign ad—or, for that matter, in a Democratic campaign ad.

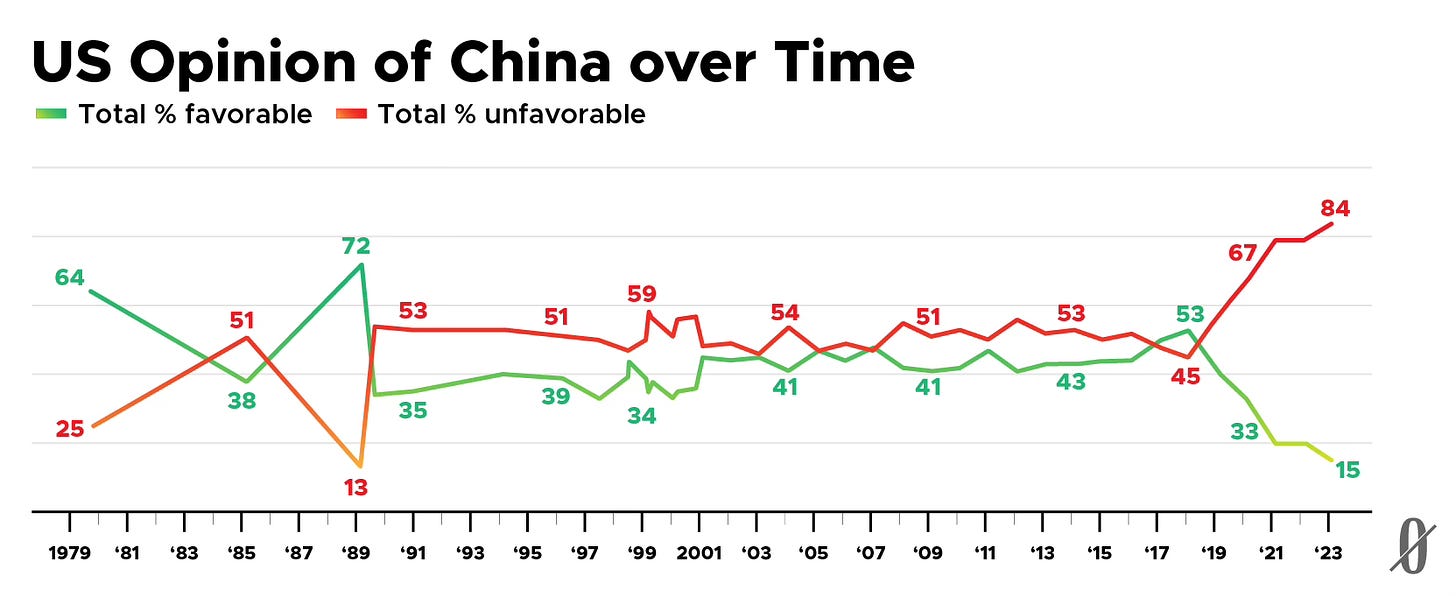

The current era of American China-bashing started during the Covid pandemic and got its initial support mainly from the Trumpist right. But Chinaphobia has since gone mainstream, and this week the Washington Post’s Liz Goodwin documented that fact. In this year’s election campaign, she reports, both Democrats and Republicans are styling themselves as tough on China and painting their opponents as pro-Beijing.

As of Monday, 171 campaign ads had mentioned China, which is also popping up in stump speeches. These mentions often go beyond promises to outcompete a rising superpower, judging by Goodwin’s examples: J.D. Vance has insinuated that Tim Walz is a Chinese plant; Democratic Senator Bob Casey has tied his Republican challenger to a Chinese firm that makes fentanyl (without mentioning that the fentanyl the firm makes is used as a pain reliever in US hospitals); the GOP gave the epithet “Shanghai Slotkin” to Rep. Elissa Slotkin; and so on.

Most China-related election ads have come from Democrats. That’s a sharp contrast with the 2020 election cycle, when, according to the advertising data firm AdImpact, Republicans bought 82 percent of China-related ads for Senate candidates.

One GOP consultant, explaining why the China theme has become so prominent, noted that “China is not exactly wildly popular among Americans these days.” Maybe the political parties are just catering to this grassroots sentiment, but of course the causal arrow can point the other way, too. In the past few years, antipathy toward China has become nearly universal in America’s political establishment, and Americans have been inundated with anti-China rhetoric. Someday this flood may subside, but not between now and the first Tuesday in November.

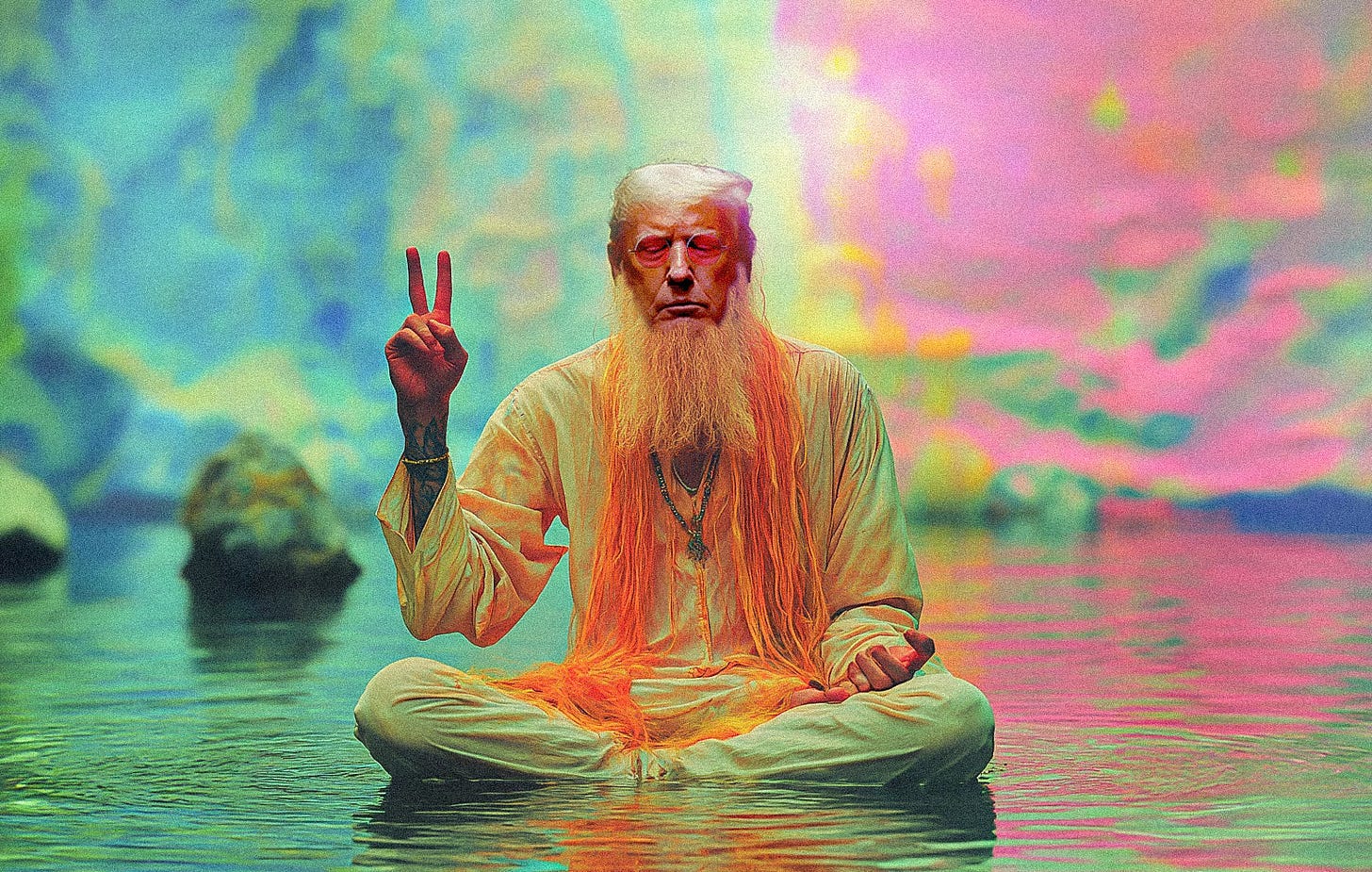

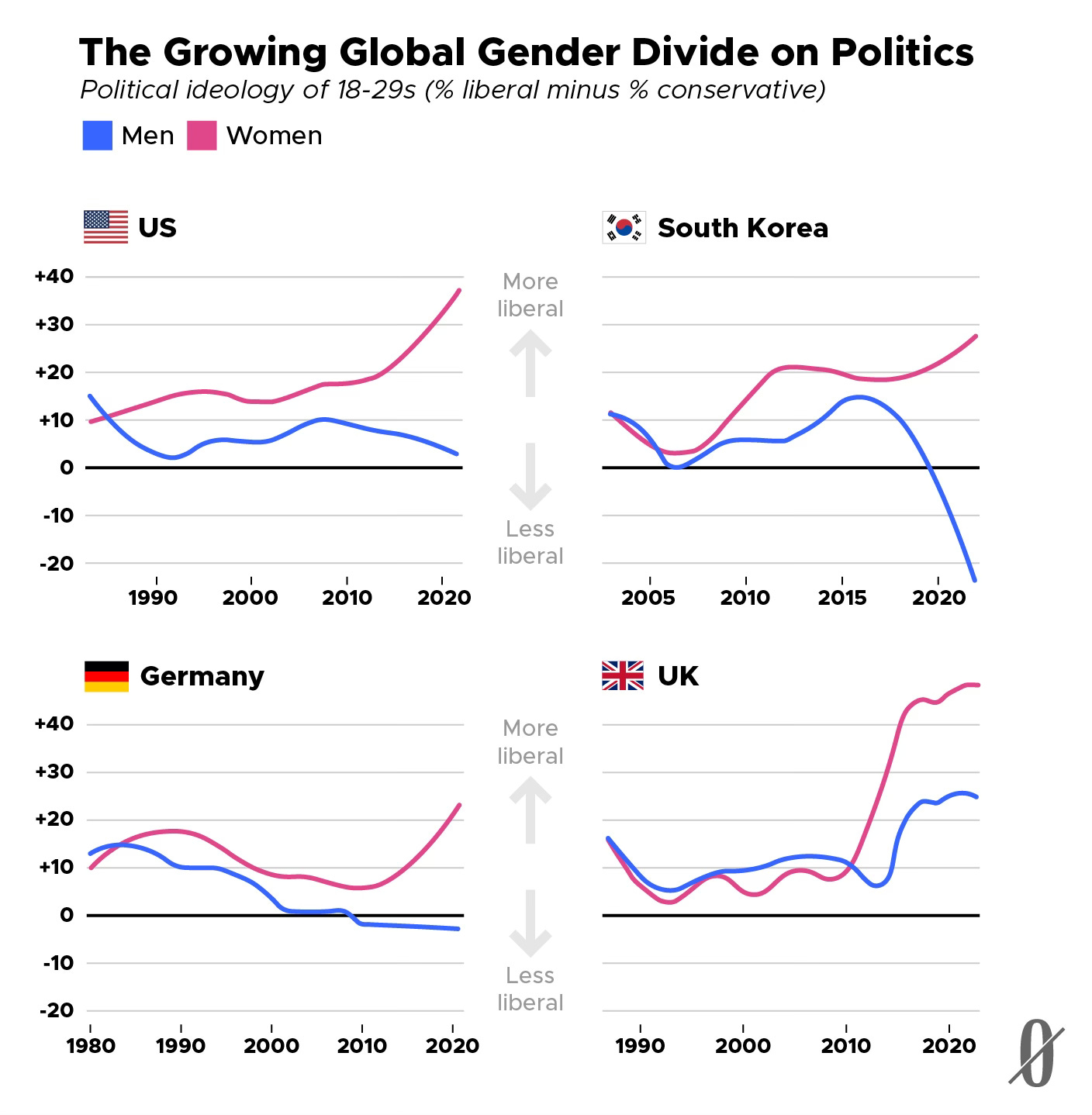

As Vice President Kamala Harris struggles to win over young male voters, some hope her running mate, folksy former football coach Tim Walz, can save the day. But the problem may be too deep for one man to solve. For years, the Democratic Party has had growing trouble attracting American men between the ages of 18 and 29:

Actually, the problem may be even deeper than that. There are signs that Generation Z is undergoing a Great Global Gender Divergence. In many developed countries, the past decade has seen young women become more liberal while young men either trended conservative or didn’t trend much at all.

Observers have offered various explanations for this growing gender gap. Some highlight the fact that the two groups tend to occupy different online spaces. Young men seem more drawn to conservative commentators who preach a return to traditional gender roles, while young women consume more feminist content. Others note that left-of-center parties have increasingly focused on women’s issues like abortion while parties on the right have emphasized economic problems that disproportionately impact young men, like deindustrialization.

Of course, with both of these explanations, you have the usual challenge of disentangling cause and effect. But we’re confident that NZN readers can get to the bottom of this. So feel free to leave your theories in the comments section: Why do young men and women seem to be dividing more clearly along ideological lines?

Political scientist John Mearsheimer famously predicted, a decade ago, that if the West continued to pull Ukraine into its orbit, the country would get “wrecked” by Russia. Two and a half years ago, Russia invaded—and the war has since taken a huge toll on Ukraine’s people and its infrastructure. But is it wrecked? And is its viability as a nation state now in doubt?

Anatol Lieven, a Russia expert at the Quincy Institute, came on the Nonzero podcast yesterday and discussed many aspects of the war, including the Kursk invasion, Zelensky’s cabinet shakeup, and what kind of eventual peace deal foreign policy elites in Moscow (which he recently visited) are envisioning. In the Overtime segment, he considered the wreckage of Ukraine:

Bob: A lot of men have left the country. A lot of women have left the country... A lot of those people who left the country, they're not coming back... And then there's all the people who have just flat out died, lost arms, lost legs... How perilous is it for Ukraine as a viable nation state to let this war go on another nine months or so?