Special Cold War Freak-Out Issue

China and Russia and Cuba—oh my! Plus: Zoom AMA TODAY, Elon’s secret spy deal, climate mystery, and more!

Senator Marco Rubio is pretty sure that the Chinese government is using the Chinese-owned social media app TikTok to undermine Israel. “TikTok is a tool China uses to spread propaganda to Americans, now it's being used to downplay Hamas terrorism,” he tweeted in November. Rubio is also sure about how to handle a problem like this: “TikTok needs to be shut down. Now.”

Jonathan Greenblatt, head of the Anti-Defamation League and as reliable a supporter of Israeli policies as Rubio (which is saying something), agrees that Congress must find a way of “holding [TikTok] accountable.” But Greenblatt may have a more nuanced grasp of the challenge TikTok poses than Rubio. In a leaked audio from a November conference call, Greenblatt said, “We have a major, major, major generational problem. All the polling I’ve seen… suggests this is not a left-right gap, folks. The issue of United States support for Israel is not left and right. It is young and old. The numbers of young people who think that Hamas’s massacre was justified is shockingly and terrifyingly high. And so we really have a Tik Tok problem, a Gen Z problem.”

Though Greenblatt’s remarks leave some room for interpretation, he seems to be acknowledging that TikTok isn’t manufacturing anti-Israel sentiment so much as reflecting the views of its overwhelmingly young (and international) user base.

At any rate, there’s no good evidence that, on the issue of Israel-Palestine, TikTok is doing more than that—conveying the sentiments of its demographic (and automatically amplifying whatever sentiment prevails in its demographic at any given moment, as social media algorithms, for better or worse, tend to do).

The absence of good evidence is a recurring theme in arguments against TikTok. The foundational premise of many of these arguments is that TikTok’s parent company, ByteDance, does the bidding of the Chinese government—in which case Beijing could use TikTok to sway American opinion or siphon data from Americans. Yet, as Ken Klippenstein noted this week in the Intercept, “US intelligence has produced no evidence that the popular social media site has ever coordinated with Beijing.”

Notwithstanding this shortage of evidence, the House has now passed—and the Senate will eventually take up—a bill that would ban TikTok in the US unless ByteDance sells it to a non-Chinese entity within six months.

There are non-crazy arguments in favor of this bill. For example: Beijing doesn’t let the big US-based social media companies do business in China, so why should the US let ByteDance do business here? But there are non-crazy replies to some of these arguments. Like: Because the US, unlike China, is a liberal democracy that professes to champion the free flow of information (even when the information comes from Gen Zers and Millennials and doesn’t sit well with Marco Rubio or Jonathan Greenblatt).

Another non-crazy argument in favor of the bill is that China’s government has more control over Chinese companies than the US has over American companies and so might at this very moment be using TikTok as a tool of influence or espionage. Here, too, there are non-crazy replies. Like: The word “might” is doing a lot of work here! If Beijing is indeed using TikTok nefariously, shouldn’t America’s vast and powerful intelligence apparatus be able to find at least some evidence of that? And surely if there were such evidence, it would be leaked to the media any day now, as the national security establishment puts its shoulder behind the TikTok bill?

Again, you wouldn’t have to be crazy to support the anti-TikTok legislation. You could be a sane person whose motto is “always err on the side of caution.” Still, when legislation this intrusive, based on scenarios this hypothetical, not only passes the House but passes by a vote of 352 to 65, you have to conclude that there’s a lot of not-very-firmly-grounded fear floating around in this country.

No surprise there. After all, the previous Cold War featured lots of unhinged fears—hence the Hollywood blacklists and other McCarthyite repression, the FBI’s attempt to blackmail suspected Communist Martin Luther King into committing suicide, and so on. The current Cold War hasn’t fully ramped up, but we are already seeing the kind of threat inflation that led to the insanity of the 1950s and 1960s.

Cold War II itself, in its current inchoate form, might not have been enough to get the TikTok bill off the ground. But synergy between China hawks and pro-Israel hawks, like Rubio and Greenblatt, was enough to provide critical mass. The Wall Street Journal, recounting the efforts of a congressional staffer who was trying to organize a coalition that would back anti-Tik-Tok legislation, reports that, “It was slow going until Oct. 7. The attack that day in Israel by Hamas and the ensuing conflict in Gaza became a turning point in the push against TikTok.”

One difference between this Cold War and the last one is that these days a bigger portion of international commerce involves products that feature lots of information processing—so a bigger portion of trade can be restricted out of fear of spying or foreign influence. This month the Chinese electronics company Xiaomi will start selling, in China, an EV that could eventually be a serious rival to Tesla. But how do we know the car won’t eavesdrop on us—and then, if we speak ill of China, drive us off a cliff? You may laugh, but some version of Chinese EV paranoia is probably around the corner.

This kind of atmosphere makes it easier for American companies—Tesla in the case of Xiaomi, Meta in the case of TikTok—to lobby for protection from foreign competition. Which is a shame, because economic engagement can temper some of the dangers of a Cold war.

Again, it’s not crazy to think that a powerful country might use social media to meddle in the internal affairs of a rival power. For example: This week Reuters reported that during the Trump administration the CIA began “a clandestine campaign on Chinese social media aimed at turning public opinion in China against its government.” The program was designed to, among other things, “foment paranoia among top leaders there.”

So why wouldn’t China do likewise, and try to foment paranoia among Americans? On the other hand, why would it bother when Americans are already doing such a good job of that?

The chief foreign-affairs correspondent of the Wall Street Journal, Yaroslav Trofimov, reports the following on Twitter: The Republicans’ blocking of US arms transfers to Ukraine “has made Putin drop his pretense about desiring peace talks. He wants it all.” To back up this claim, Trofimov quotes Putin saying, in a recent interview, “It would be ridiculous for us to start negotiating with Ukraine just because it’s running out of ammunition.”

But there’s a problem with Trofimov’s reporting, notes Jacobin staff writer Branko Marcetic in Responsible Statecraft. Namely: “[T]hat’s not what Putin said. In fact, by reading the full text and seeing the quote in context instead of as a selectively edited soundbite, it’s clear he was putting out the exact opposite message.”

Here’s the next part of Putin’s quote, which Trofimov left out: “Nevertheless, we are open to a serious discussion, and we are eager to resolve all conflicts, especially this one, by peaceful means.” There were other parts of Putin’s remarks that Trofimov didn’t quote but that are relevant to the issue at hand. For example: “Are we ready to negotiate? We sure are.”

If the Wall Street Journal’s chief foreign policy correspondent can’t be trusted to report objectively on Russia, who can? Maybe the seasoned journalists at the New York Times? Well…

Last week NYT international correspondent Valerie Hopkins went on the Times podcast The Daily to chat with host Sabrina Tavernise, a former Moscow correspondent for the Times.

Hopkins reported that when a Russian soldier dies in Ukraine his family can get “up to 60, 70, 80 thousand dollars in compensation payments.” Tavernise said this is “quite cunning of Putin—that there is an economic element to this war for the people who are dying, and that is something that can blunt any political opposition to it. So the people doing the dying are not going to be the people asking the questions, in part because this money is coming in” (and in part because they’re dead, but we digress…) Hopkins agreed with Tavernise that Putin’s policy “does have an effect of making these families far less vocal and far less prone to uniting in some kind of protest movement that could challenge Putin.”

A question for Tavernise and Hopkins: If payments of up to $80,000 to the families of dead soldiers are a “very cunning” way to stifle dissent about war, what are the payments of $100,000 that the US government gives to the families of soldiers who die on the battlefield? A very, very cunning way to stifle dissent?

Hopkins also said Putin has talked about giving military veterans “more leadership roles and more opportunities, and this is widely perceived as an attempt by Putin to re-engineer a new middle class comprised of people involved in the war effort.” Tavernise replied that this policy, in conjunction with the payments to bereaved families, is “very dark.” Maybe her next podcast can be about the very dark G.I. Bill and its various very dark successors, which have propelled millions of American veterans into the middle class by paying for their college educations.

NZN has long preached the virtues of trying to comprehend diverse perspectives, including—especially including—the perspectives of enemies and others whose world views you may find alien. Yesterday the NonZero podcast aired a conversation with the hosts of the Russians with Attitude podcast—both of whom supported their country’s invasion of Ukraine. (Is there another podcast out there that’s given a platform to pro-Putin Russian nationalists like these and anti-Putin Russians like journalist Leonid Ragozin and fierce Russia hawks like Anders Aslund?)

At one point in the conversation, one of the guests, Kirill, defended a tweet of his that expressed his (unsettling) view that Russia should recover ethnically Russian lands that Moscow lost with the collapse of the Soviet Union. Which raises a question: Is Putin himself motivated by this expansively nationalist spirit? According to Kirill, no—and here Putin stands in contrast to the large number of Russians who are true hardliners:

One thing I always repeat, and that people in the West often don't believe, is that in terms of revanchism, nationalism, expansionism, Putin and the current Russian government are not just moderate, they are less than moderate. There is a very strong current in Russia that is much more hardline, including among the elites. And Putin does not represent, in any way, the peak of what an actually resentful, revanchist Russian government would look like.

And I think it would be for the best for everyone if such a government were not formed. I am more than happy with the moderate approach, at least at the moment.

You can listen to the rest of the conversation, including (for paid NZN subscribers) the Overtime segment, here.

Elon Musk’s SpaceX has a secret contract with the US government to build a network of hundreds of low-orbit spy satellites, Reuters reports.

The system, when deployed, will enable the US “to quickly capture continuous imagery of activities on the ground nearly anywhere on the globe, aiding intelligence and military operations,” Reuters writes. Or, as an anonymous source who is “familiar with the program” told Reuters: “No one can hide.”

The $1.8 billion SpaceX contract was signed in 2021 with the National Reconnaissance Office, which manages the government’s spy satellites. The satellite network is under construction but isn’t yet online, Reuters says.

This week, the European Parliament passed the EU’s big, years-in-the-making AI Act, which will become law in May but won’t come into full force until 2027.

Some uses of AI will be banned outright. These range from the vaguely defined (“subliminal, manipulative, or deceptive techniques to distort behavior and impair informed decision-making”) to the clear and concrete—like using facial recognition surveillance technology in public. The law carves out exceptions for law enforcement authorities.

AI firms will be required to label deepfakes and make sure people know when they’re conversing with a chatbot. And companies that build large language models will have to provide a summary of their training data, among other transparency requirements. A new European AI Office will verify compliance and field complaints from EU citizens who say they’ve been harmed by AI.

The makers of free open-source models—who disclose information about the models’ training and fine tuning and resulting internal calibrations—are spared many of the act’s strictures. A cynic might wonder if that has less to do with AI safety and more to do with the fact that Europe’s most formidable maker of LLMs—the French company Mistral—builds open source models. Last week, NZN highlighted some of the dangers of open-source AI.

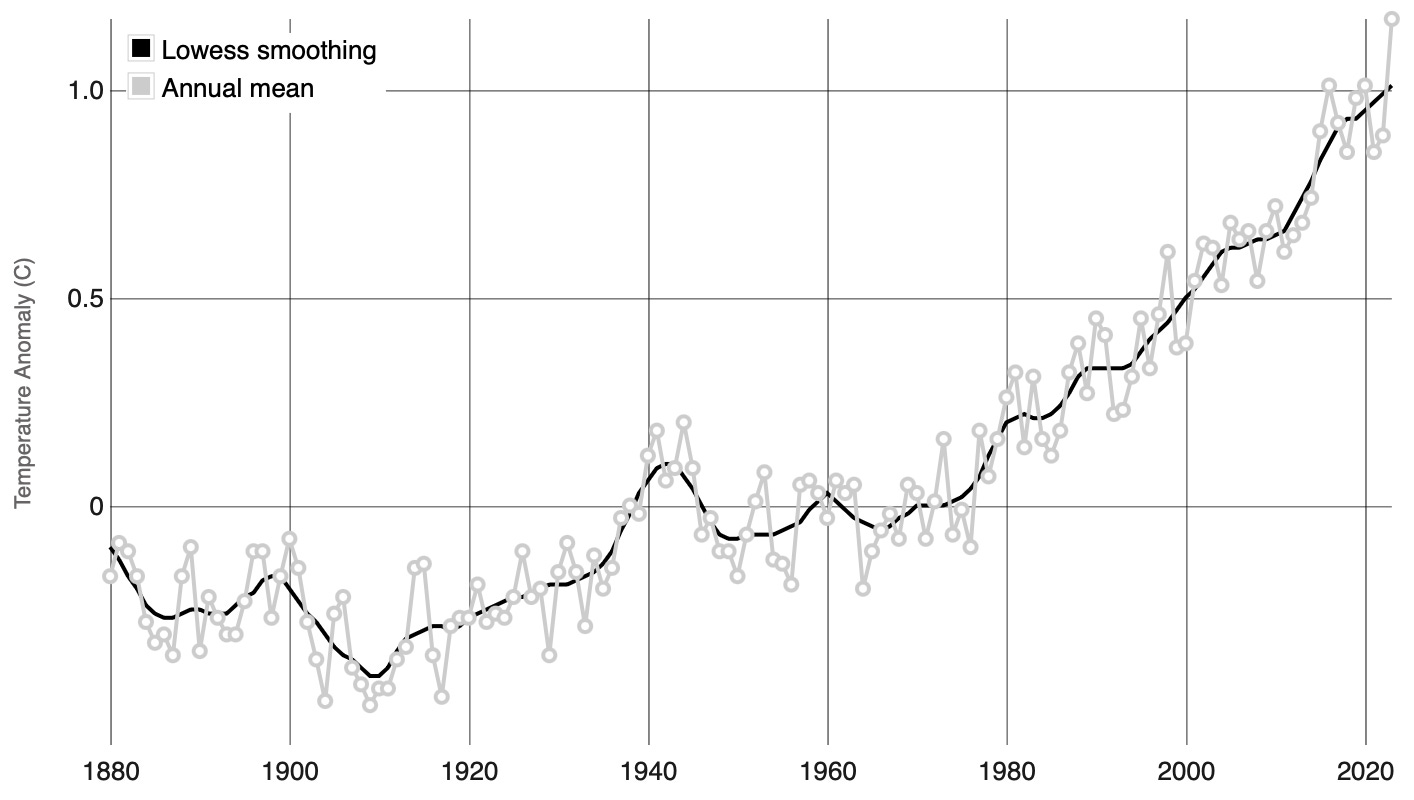

Last year wasn’t just the hottest year on record. It was hotter than the previous holder of that title by a record-setting increment (0.27 degrees Fahrenheit).

What does this mean? Are we entering a phase of accelerated global warming? For the answer we turn to the experts:

“It’s humbling, and a bit worrying, to admit that no year has confounded climate scientists’ predictive capabilities more than 2023 has,” Gavin Schmidt, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, writes in Nature. And, no, El Niño, which increases the planet’s surface temperature, doesn’t explain the surprise. The unusual rise in temperature began before El Niño showed up in June.

Other possible explanations: 1) A 2022 volcano in Tonga may have had lingering warming effects. 2) There was an uptick in solar flares last year. 3) International rules passed in 2020 cut sulfur emissions in the shipping industry—and these emissions, though toxic, did have the virtue of bouncing sunlight back into outer space.

But scientists doubt that all of these factors taken together can explain last year’s jump in temperature. So maybe, says Schmidt, “a warming planet is already fundamentally altering how the climate system operates, much sooner than scientists had anticipated.”

Was the “Havana Syndrome”—the mysterious affliction reported by US diplomats in Cuba and by US personnel in other countries—all in the heads of those who suffered from it? Depends on what you mean by “in the heads.”

Two new studies by the National Institutes of Health find no evidence of brain injury in victims—a significant result, since the syndrome purportedly involved neurological problems. But as for the other sense of “in the heads”: Yes, the NIH finding adds to the evidence that, as NZN put it in 2021, Havana Syndrome was likely “a ‘mass sociogenic illness’—a melange of symptoms, some real, some imagined, all attributed to a single cause that doesn’t, in fact, exist (but discussion of which generates more and more reports of symptoms).”

The Havana Syndrome freak-out kicked off in 2016, when diplomats started reporting such symptoms as nausea, headaches, and confusion. Some of these diplomats believed they had been targeted by directed energy weapons, claims that received sympathetic (some might say credulous) attention in mainstream media. Washington expelled Cuban diplomats in response to the conjectured attacks, and CIA Director William J. Burns later warned Russia of “consequences” if Moscow was responsible. Some suspected Chinese involvement.

The NIH finding is only the latest nail in the coffin of Havana Syndrome. Earlier this month, US intelligence agencies determined that the syndrome was not caused by a foreign adversary or by exotic weapons. But the death of Havana Syndrome doesn’t mean the death of Havana Syndrome Syndrome—which NZN defined in 2021 as “the set of psychological tendencies that led people in the Blob to take Havana Syndrome seriously.”

ZOOM AMA!! Link below to today’s 6 pm (US Eastern Time) discussion!