The military-industrial complex enters orbit

Plus: Important news from the Ukrainian front, the ideological Turing test, AI updates, NZN content bonanza, and more!

Major General David Miller, director of operations for the US Space Command, has this to say about outer space: “We’ve got to… stop debating if this is a warfighting domain… I think we're past the point of ‘Is space a warfighting domain?’ I think we're past the point of ‘Has space been weaponized?’…We are transitioning to a warfighting space force.”

Miller said these things last month at an online conference sponsored by the Mitchell Institute, which gets its funding from Lockheed Martin, BAE Systems (Europe’s largest defense contractor), Kratos Defense & Security Solutions (which specializes in directed-energy weapons), and so on. The purpose of the conference was to unveil a Mitchell Institute report that emphasized the need for… well, ultimately, for the kinds of products companies like this make. (Or, as the report stated the case: “Clear guidance, Congressional support, and unified Space Force and industry efforts are required to develop, field, and operate counterspace capabilities to enhance deterrence and create a war-winning force.”)

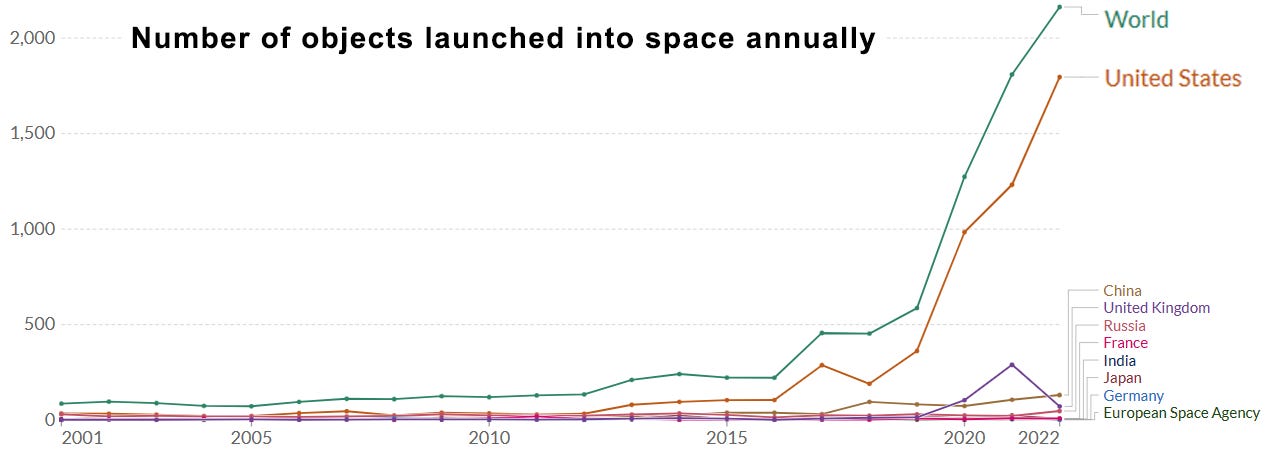

This is of course an old story: Defense contractors fund think tanks whose thinkers espouse strategies that make defense contractors richer. But in this case the consequent warping of discourse is happening at an unusually fluid and critical moment. As the number of satellites in orbit grows rapidly, space-based technology is becoming vital to the everyday functioning of the planet. Yet the international governance of outer space has advanced only marginally since the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, which banned nuclear weapons in space but did little else to keep things peaceful and orderly there.

In fact, the Mitchell Institute’s report notes as much: “There are no formal internationally recognized agreements prohibiting the development and fielding of space weapons.” The report then warns that “potential adversaries have been exploiting the lack of clarity” by, for example, testing anti-satellite weapons (which the US has done, too, but not as recently as Russia and China).

One solution to this problem, in principle, would be to establish such clarity—to finally, half a century after Planet Earth forged its only major space treaty, pursue another, very ambitious, one. The Mitchell Institute favors a different approach: “US national policy must recognize the inability of norms and defensive measures alone to credibly deter threats or provide war-winning forces to defeat aggression in space. Space is now a warfighting domain, and there are ways to responsibly conduct warfare in space.”

That reassurance—that war in space can be conducted “responsibly”—feels a little hollow, coming in a report that also acknowledges the growing plausibility of the “Kessler Syndrome.” In the Kessler scenario, an increasingly crowded outer space is a place where a single smashed satellite can create enough debris to start a massive chain reaction of satellite destruction, creating a cascade of space junk that might not end until it ran out of satellites to swallow.

The consequences could range from downed power grids to global communications failures to something more worrying than either of those things: The sudden and widespread outage of satellite surveillance could make nuclear-armed nations jumpier, since they’d lack the usual reassurance that their rivals weren’t mobilizing for attack. And if the satellite smashing that triggered the Kessler Syndrome was an act of war—part of the space warfare that the Mitchell Institute assures us can be conducted “responsibly”—then the nuclear powers in question would be not just rivals but combatants. That’s the kind of situation that could have very unfortunate consequences.

The arguments for the militarization of outer space being made by the Mitchell Institute, and by Gen. Miller, deserve a hearing. One of their (implicit) premises—that forging a treaty which effectively limits the militarization of outer space would be challenging for both technical and geopolitical reasons—is certainly true.

The problem is that these pro-space-militarization arguments should have informed and powerful pushback. And there’s no money in pushback—there’s no well-funded counterpart to the military industrial complex that’s focusing on these issues. (The only DC think tank that seems interested in significantly advancing space governance is the Rand Corporation—and it, unlike the military industrial complex, doesn’t send lobbyists to Capitol Hill to put its money where its mouth is.) And there’s no grassroots anti-space-militarization constituency to pick up the slack.

Here’s the kind of argument that someone in America’s foreign policy community might make if that community included people inclined to give the Mitchell Institute pushback:

If (1) America’s current relationship with Russia and China precludes the pursuit of a new space treaty, and indeed fosters an environment of mutual suspicion that could lead to the headlong militarization of outer space; and if (2) the headlong militarization of outer space stands a non-trivial chance of ushering in Armageddon; then maybe (3) we should put a higher priority on improving relations with Russia and China—even if that means putting a lower priority on some of our current goals. (Such goals as wresting a few more square miles of turf from Russian occupiers in Ukraine, at the cost of many lives, rather than pursuing peace.)

This is, by the standards of America’s foreign policy community, a radical argument. Then again, Armageddon is a radically bad thing. That’s why we need a serious debate about whether there’s a way to keep outer space from being a warfighting domain.

Have you noticed that people who disagree with you on the great issues of the day tend to be confused—that they cling to arguments devoid of logic and evidence? Plus, don’t some of them seem like bad people, lacking the kind of reliable moral gyroscope that guides you?

A recent study brings painful news: This may all be in your head.

The study involved the “ideological Turing Test,” which works like this: You try to construct the strongest argument on behalf of a position you disagree with. If you do such a good job that people who hold that position find the argument as strong as arguments mounted by people who actually share their position, you’ve passed the test; you understand the arguments on the opposing side so well that you can convincingly mimic them.

In this study, researchers at the University of Sheffield asked people to formulate arguments for and against their positions on three issues—Covid vaccines, Brexit, and veganism. Then the researchers showed arguments favoring a given position to people who held that position, without telling them whether the argument had been formulated by someone who also held the position or by someone who opposed it. After reading each argument, these people recorded their degree of agreement with it.

The study found that “those who pass the ideological Turing Test are less judgmental towards their opponents, in that they are less likely to rate them as ignorant, immoral or irrational.”

The question of causal direction remains: Do we think poorly of ideological opponents because we’ve heard only the weakest versions of their arguments, or do we start out with a low opinion of them and then, in keeping with confirmation bias, avoid exploring their arguments thoroughly enough to challenge that opinion? Or both?

Whatever the exact dynamic, remember: The surer you are that someone is confused or uninformed or just plain bad, the more likely it is that you don’t understand what they’re saying.

This is the kind of finding that, if people really took it to heart, could change the world.

NZN content bonanza!

Be sure to check out Overton Windows, Bob’s new podcast mini-series with philosopher Tamler Sommers. The first episode, What You Can and Can’t Say about Israel/Palestine, is available to all, but future episodes will be paywalled. You can listen to the episode here or in your Nonzero Podcast feed.

Paid subscribers can now listen to an audio version of Bob’s essay “Artificial Intelligence and the Noosphere.” Published last month, the essay is the first in an occasional series on AI viewed in cosmic perspective. Look for the new audio essay (and the perks below) in the paid-subscriber podcast feed. (To set that up, just click either of the two audio links above, then click “Listen on,” and follow the instructions).

Tonight, as usual on weekends, paid subscribers will have access to the latest edition of the Parrot Room, Bob’s after-hours conversation with Mickey Kaus. The Parrot Room airs shortly after the public Bob-and-Mickey podcast.

Reminder: Paid subscribers get early access to Bob’s conversation with Connor Leahy, CEO of Conjecture AI, about AI and existential risk. The episode will go public on Tuesday, though the Overtime segment will remain exclusive.

Several prominent military analysts—Michael Kofman, Rob Lee, and Franz-Stefan Gady—recently concluded a fact-finding visit to Ukraine, and this week they began sharing their findings. One thing all three assessments of Ukraine’s six-week-old counter-offensive have in common is that they’re not encouraging.

For starters: A key part of the preparation for the offensive—NATO’s training of nine newly assembled and freshly equipped brigades in Europe—didn’t work. The tens of thousands of soldiers in these brigades were supposed to learn “combined arms warfare”—the close coordination of diverse elements, such as infantry, tanks, and artillery, on a large scale. But the soldiers didn’t have much time to train, and most were fresh conscripts, lacking battlefield experience.

“Ukrainian forces have still not mastered combined arms operations at scale,” wrote Gady in a widely-circulated Twitter thread. As a result of this and other problems, “there’s simply no systematic pulling apart of the Russian defensive system that I could observe…” Ukraine has switched tactics, using small deployments of infantry backed by artillery. “Progress is measured by yards/meters and not km/miles.”

These meager gains are coming at a high cost in casualties. And, though Gady says morale remains high, “there are some force quality issues emerging with less able bodied & older men called up for service now.”

Koffman and Lee, speaking on the War on the Rocks podcast, noted the strengths being shown by the enemy. Russians have learned from mistakes made early in the war, and their defensive fortifications are massive, featuring lots and lots of barriers, mines, and trenches (some of which are left vacant and booby trapped). And as for the western minesweeping vehicles that were supposed to pave the way: the Russians are using stacks of three anti-tank mines to disable them.

All these analysts are very pro-Ukraine, and they all favor giving Ukraine not just more arms but more kinds of arms, including the controversial cluster munitions that the US is now providing. But their assessments could make one wonder what the point of all the carnage is, given that big gains seem unlikely barring a sudden Russian collapse. Might it be time for the Biden administration to finally start pushing Ukraine toward a ceasefire and peace talks (which many observers say Putin is ready for but which Zelensky opposes so long as a single Russian soldier stands on Ukrainian soil)?

Among the most arresting evidence that could be used in support of such a proposal comes from things Dmitri Alperovitch said on his podcast as preface to an interview he conducted with Kofman and Lee on the train to Kyiv. He’d recorded the preface days after the interview, after getting a sense for the toll that all the casualties are taking on the psychological state of the Ukrainian people. He said: