The truth about Hamas

Plus: OpenAI’s new job-destroying tool, China’s nuke buildup, China’s CO2 drawdown, why presidential candidates are hawkish, and more!

Ever wonder how Hamas came to be running Gaza in the first place? Don’t bother Googling it, because the chances are you’ll wind up reading one of the accounts floating around in the mainstream media, and pretty much all of those are seriously misleading.

And they’re consequentially misleading. They could warp your thinking about how we should handle Hamas and extremist groups in general. And they obscure the fact that American policies, by making a solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict less likely, have made atrocities like Hamas’s October 7 attack more likely.

A typically misleading account can be found in a recent Atlantic piece by historian Simon Sebag Montefiore. The piece (aimed at debunking a particular left-wing framing of the Israel-Palestine conflict) disposes of the question of how Hamas rose to power in a mere 23 words: “Israel evacuated the [Gaza] Strip in 2005, removing its settlements. In 2007, Hamas seized power, killing its Fatah rivals in a short civil war.” In other accounts, like this NPR story from a few years ago, this vanquishing of Fatah (the political party that still dominates politics in the West Bank) is described as a “coup.”

Among the facts missing from Montefiore’s account is that, in a 2006 election, Hamas had won control of the Palestinian Legislative Council, which represented Palestinians in both Gaza and the West Bank. Since October 7, this fact, when mentioned at all, has typically been mentioned as a way of blaming the civilians getting bombed in Gaza for getting bombed. Famous law professor Alan Dershowitz, for example, recently said that “the citizens of Gaza—these innocent civilians who so many people are shedding tears about—they voted for Hamas… they’re supporters of Hamas.” (The fact that about one fourth of current Gaza residents were of voting age in 2006—and that Hamas got only 44 percent of the popular vote—doesn’t faze people like Dershowitz.) But the 2006 election, viewed in light of the events that followed it, turns out to have a very different kind of relevance to the current killing of people in Gaza.

Hamas’s control of the legislative council should in theory have given it effective control of Palestinian governance, because authority over the Palestinian Authority’s financial and security affairs had recently been moved from the president (who then as now was Mahmoud Abbas) to the prime minister. This raises a puzzle. Why would Hamas stage a “coup”? Was it trying to overthrow itself? Or, if you accept Montefiore’s framing of the Hamas-Fatah conflict as a civil war, who started the civil war? Presumably Hamas, like most ruling parties, would just as soon have avoided one.

A big part of the answer is something almost nobody talks about: the US decided to back a regime change effort after Hamas became the inchoate regime. The George W. Bush administration, ideologically committed to democracy promotion, had pushed hard for Palestinian elections and had said it was fine for Hamas to participate. But the administration hadn’t said it was fine for Hamas to win. Democracy promotion has its limits! So when Hamas won, remedial action was in order.

The Bush administration pushed President Abbas to wrest influence from Hamas in ways that were sure to antagonize it (and that in some cases may have exceeded his legal authority). Meanwhile, the administration set about starving the Hamas-run government of resources and then steered resources to Fatah, Abbas’s party, so that Fatah could overpower Hamas when push came to shove. The administration tried to get several Arab states to funnel weapons to Fatah, and in the case of Egypt it succeeded.

After the Gaza civil war ended, David Wurmser, who had served in the Bush Administration and opposed its attempt to depose Hamas, said that in his view “what happened wasn’t so much a coup by Hamas but an attempted coup by Fatah that was pre-empted before it could happen.”

Wurmser said that to David Rose, whose pioneering reporting, laid out in a 2008 Vanity Fair piece, is the basis for parts of the account above. If you want more of the gruesome details about the regime change operation—torture practiced by US proxies, for example—see Rose’s piece. For present purposes what’s more important than the operation itself is what it derailed: a chance to see if Hamas could be steered toward moderation and play a constructive role—or at least a non-obstructive role—in a resolution of the Israel-Palestine conflict.

In the days after the election, reporters asked Hamas leaders whether, now that they had actual governing authority, they would explore diplomacy with Israel and possibly even acknowledge its right to exist, rather than continue their holy war against it. Significantly, these leaders didn’t rule that possibility out. (At least, it seemed significant to me, and I complained at the time that media accounts were obscuring it.)

What’s more, Mahmoud Abbas—who as head of Fatah presumably had deeper insight into the mindsight of Hamas’s leadership than, say, George W. Bush—believed that Hamas was willing to work with his party to form a unity government. In a 2013 New Republic piece that integrates Rose’s reporting with other evidence and puts the story in geopolitical context, John Judis wrote:

According to a mission report from [Alvaro] de Soto, who was the UN representative to the Middle East Quartet, Abbas and the Hamas officials wanted to create a unity government of the two parties. Abbas was convinced that Hamas, which had not campaigned against a two-state solution, would allow him to pursue negotiations with Israel. And de Soto and the UN wanted the Quartet to open a “channel of dialogue” with Hamas.

But the United States—which, along with Russia, the UN, and the EU, constituted the Quartet, and was its most influential member—wasn’t willing to engage Hamas.

As it happened, Saudi Arabia was. Judis writes:

[I]n February [of 2007, after months of fighting between Fatah and Hamas], the Saudis surprised the Quartet members by bringing Hamas and Fatah leaders to Mecca for unity talks that resulted in an agreement between the two sides establishing a new government. The government included prominent Fatah and Hamas officials as well as several academics and policy experts… The two sides agreed that Hamas would handle domestic matters and Fatah and the independent experts international affairs, including negotiations with Israel.

In Mecca, Khalid Mishal, then the leader of Hamas, agreed to abide by the Oslo accords and other existing treaties between the PLO and Israel, and to support negotiations over a two-state solution. After the Mecca talks he said, “Hamas is adopting a new political language. The Mecca agreement is a new political language ... and honoring the agreements is a new language, because there is a national need and we must speak a language appropriate to the time.”

None of this was enough to satisfy the Bush administration. It continued to demand, via the Quartet, that Hamas make several more commitments, and that it recognize the state of Israel. This (something Saudi Arabia itself hadn’t done, and still hasn’t done) would have constituted a sudden and radical reversal for an organization that had long made ending Zionism central to its mission. To demand that concession was basically to make Hamas an offer that it was bound to refuse.

Does that mean Hamas never could have recognized Israel? Not necessarily. Groups change. The PLO was once bent on ending Zionism, and saw killing civilians as a legitimate means to that end, but in 1993 it recognized Israel’s right to exist.

Changing Hamas that much—assuming it was possible at all—would have required years of patient and wise diplomacy—and patience and wisdom weren’t the hallmarks of Bush’s foreign policy. (In fact, they haven’t characterized American foreign policy generally in recent decades.)

The failed attempt to violently depose Hamas helped set the stage for further trouble, including the kind we saw on October 7. It had looked at times, in the aftermath of the 2006 election, as if there would be unified Palestinian governance of Gaza and the West Bank. The agreement in Mecca between Fatah and Hamas seemed as if it might realize that promise—and, what’s more, sustain a peace dialogue between the Palestinians and Israel. But the refusal of the US to bless that agreement, and the ensuing resumption of violence between Hamas and Fatah, enduringly fractured Palestinian governance, creating a Hamas-led Gaza and a Fatah-led West Bank.

At the time, Judis notes, the head of Israel’s military intelligence said he was happy with that outcome because it would allow Israel to treat Gaza as “hostile territory.” And certainly Israeli politicians since then have seen the virtues of a fractured Palestine. According to the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, Bibi Netanyahu, in a 2019 meeting of Likud members of the Knesset, explained why he tolerates the Qatari government’s financial support of Hamas: “Anyone who wants to thwart the establishment of a Palestinian state has to support bolstering Hamas and transferring money to Hamas. This is part of our strategy —to isolate the Palestinians in Gaza from the Palestinians in the West Bank.”

People’s ideas about how to deal with Hamas after October 7 tend to depend on what they think Hamas is. At one end of the spectrum is the “essentialist” view: At the core of Hamas lies something unalterably bad—if not evil itself then at least an incorrigibly violent and fanatical character. So the only hope is to “eliminate” Hamas.

At the other end of the spectrum is a view that is more optimistic though in a sense more cynical: Hamas is composed of human beings who are fundamentally like other human beings—which means their self-serving tendencies can in principle be harnessed to good ends. If, for example, you arrange things so they can rise in stature and influence by moderating their policies and messages, they may do that. (Khalid Mishal got a lot of favorable attention from global elites after those Mecca talks! It was within the power of George W. Bush to get him more of that.)

The essentialist view can be a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. If you see extremist groups as unalterably bad, as the Bush administration did in this case, you can wind up placing roadblocks on any path toward moderation. Then it will be easy to convince yourself that you were right, since the groups will keep behaving badly.

So what is the truth about Hamas? Is it firmly fixed on a mission of violence and destruction? Is it more malleable than that? If so, how malleable? I don’t know what the answer is now or what the answer was in 2006. But I do know that in 2006 we did something we’ve done at other times with other extremist groups: We missed a chance to find out.

Paid-subscriber perks:

Early access to Bob’s conversation with Russia expert Thomas Graham about the Ukraine war, Putin’s political and psychological evolution, and US foreign policy.

The Overtime segment of Bob’s conversation with China expert Susan Shirk. They discussed Chinese overreach, American overreaction, and how the US can prevent an invasion of Taiwan.

Is the jobocalypse—the massive displacement of workers that some fear AI will bring—upon us? Not exactly, but some observers saw glimmers of it in OpenAI’s recent unveiling of a new variant of soon-to-be one-year-old ChatGPT.

The new variant is, well, variable. Open AI is letting users create customized chatbots that it calls GPTs. As the company explained on its blog, “GPTs are a new way for anyone to create a tailored version of ChatGPT to be more helpful in their daily life, at specific tasks, at work, or at home.”

Sounds great! But New York Times tech columnist Kevin Roose got to wondering: What if the task a GPT is artisanally crafted to do is a task some human being is currently getting paid to do? After creating a few hand-crafted chatbots he wrote:

None of my custom chatbots worked perfectly, and there was plenty they couldn’t do. But if you squint, you can see hints of the kinds of jobs that autonomous AI agents could replace, if they actually work.

Imagine the benefits department at a big company. On a regular day, benefits administrators might spend 20 percent of their time answering employee questions like, “Does our dental insurance cover orthodontics?” or “What forms do I need to fill out to apply for parental leave?” Build a chatbot to answer those questions and you might free those administrators to do higher-value tasks — or you might just need 20 percent fewer of them.

Or imagine a company that trains A.I. agents to respond to the vast majority of customer service requests by feeding them information and hooking them up to a database of past customer problems. Would that company’s customer service department shrink? Could it eventually be as good as, or superior to, a customer service department staffed by humans?

Plot spoiler: Yes.

Thanks to record growth in clean energy installations—particularly wind and solar power—China’s carbon emissions are set to decline in 2024, according to a new report by Finland’s Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air.

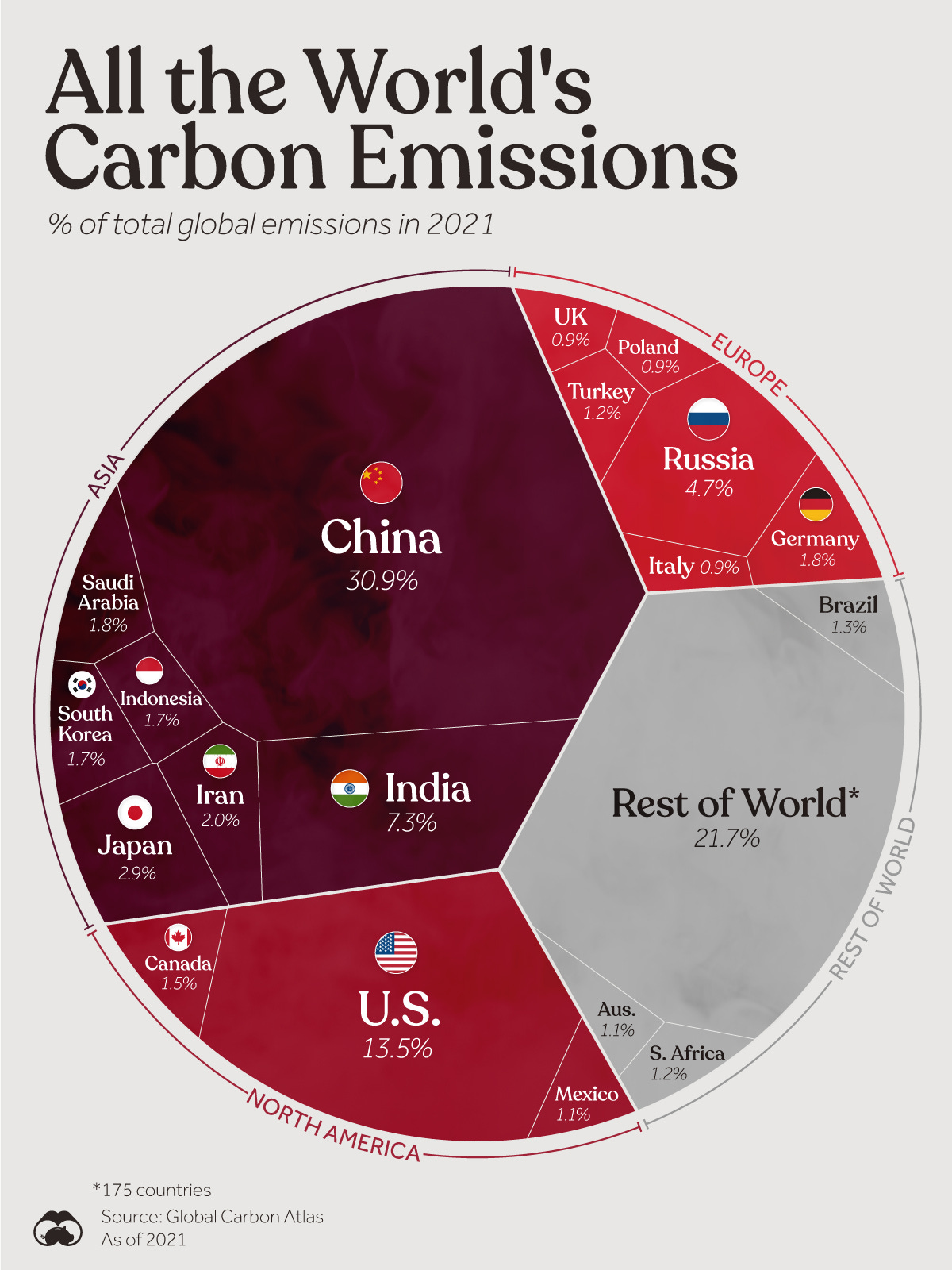

This isn’t China’s first year-to-year decline, but this time it looks like the country is entering “an extended period of structural decline.” That is, the use of clean energy is now expanding fast enough to more than compensate for the projected rate of increase in demand for electricity. That’s especially good news in light of China’s impressive contribution to global CO2 emissions:

Why is Beijing rapidly expanding its nuclear arsenal—and how should Washington respond? How you answer the second question depends on how you answer the first.